9. Heroes and Villains of the Industrial Revolution - The Transportation Revolution

- Historical Conquest Team

- Jul 18, 2025

- 42 min read

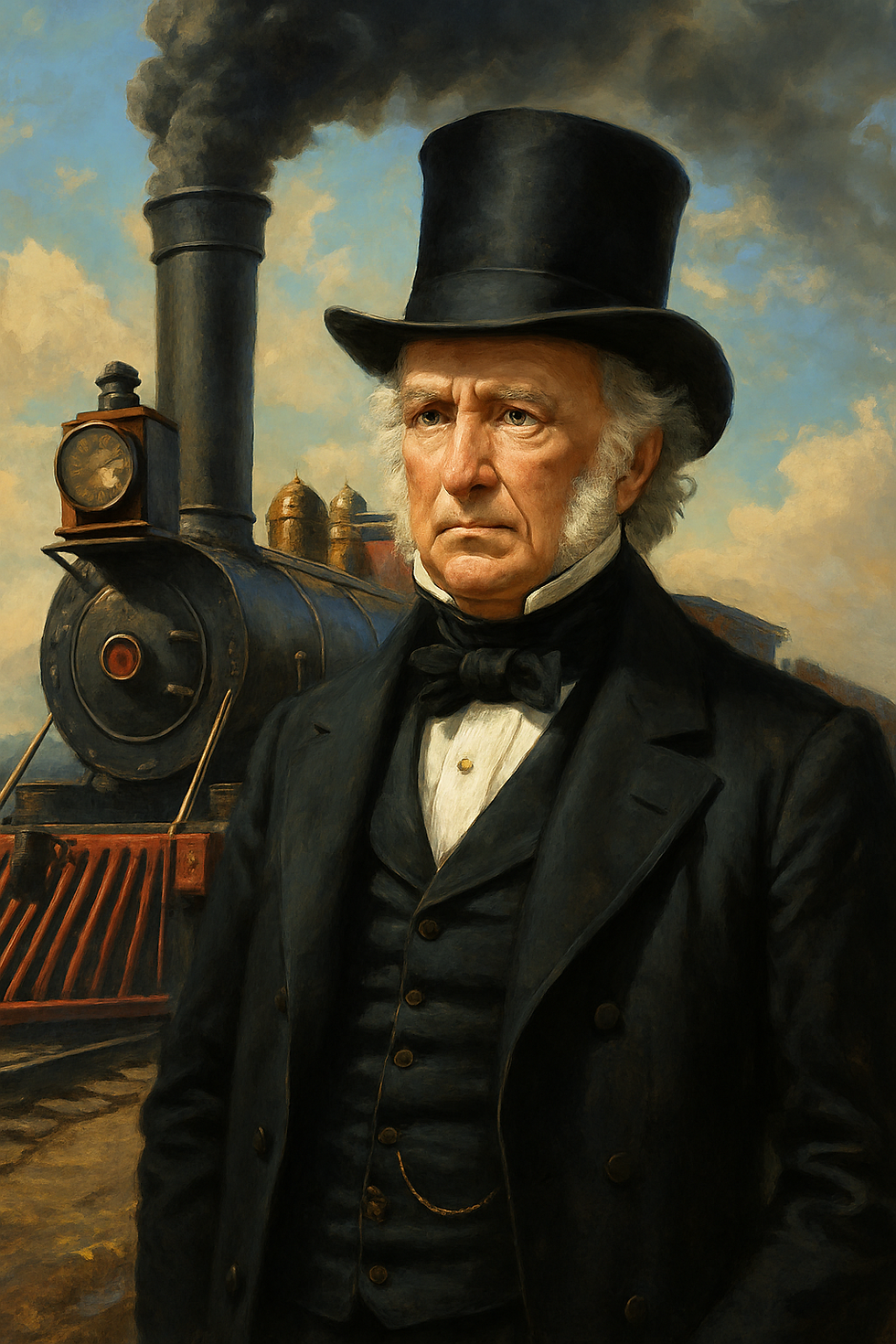

My Name is George Stephenson (1781–1848): The Father of RailroadI was born in Wylam, a small coal-mining village in Northumberland, England, in 1781. My family was poor—my father worked as a fireman tending a steam engine at a local colliery, and we lived in a modest one-room cottage. We had little money, and like many children in my time, I didn’t attend school in my early years. But I was curious. I spent much of my childhood fascinated by machines, watching how they moved, how they worked. By the time I was a teenager, I was already earning money working with engines in the coal pits.

Learning by Doing

I wasn’t born a genius or trained in fine schools. In fact, I taught myself to read and write when I was already an adult. I worked during the day and took lessons at night, sometimes paying my teacher with small coins or food. I learned mathematics and mechanics by sheer determination. My education didn’t come from books alone—it came from turning bolts, fixing parts, and solving problems with my own hands. That’s how I gained the knowledge that would eventually change the world.

Fixing Engines, Dreaming Bigger

My early work was repairing and maintaining steam engines used to pump water out of coal mines. These stationary engines were the heartbeat of industry. I became known for my skill and reliability. Eventually, I became an engine-wright at Killingworth Colliery, responsible for keeping the machines running. But I began thinking—why should engines be fixed in one place? What if they could move? What if they could carry coal, and even people, far distances?

The Birth of the Locomotive

In 1814, I built my first locomotive, the Blücher, to haul coal wagons along a wagonway at Killingworth. It wasn’t the first steam engine to move on rails, but it was one of the most practical. It used flanged wheels for better grip on the rails and could haul far more weight than horses. I improved my designs steadily. By the 1820s, I had become known as the man who could build reliable, working locomotives. I insisted on laying proper tracks, designing better engines, and training others—especially my son, Robert, who became an accomplished engineer in his own right.

The Rocket and the Railway Age

My greatest moment came with the Rainhill Trials in 1829. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway needed the best locomotive for its new public line. Several inventors entered the competition, but my engine, the Rocket, proved fastest and most reliable. It reached speeds over 25 miles per hour—unbelievable at the time! The success of the Rocket helped launch a new era: the Railway Age. Suddenly, people saw the future racing toward them on iron tracks. Railways began to spring up all across Britain and soon across the world.

Changing the World, One Track at a Time

I went on to help build many of Britain’s first major railway lines. My vision was always practical—railways should serve people, connect cities, and operate safely and efficiently. I never sought fame. I saw myself as a working man who happened to build something useful. But my work changed everything—travel became faster, goods cheaper, towns grew, and the very idea of distance shrank. Industry exploded. The locomotive didn’t just move trains; it moved society.

Looking Back

I died in 1848, having lived to see my dream spread across continents. I never forgot my roots or the value of hard work. I was proud that a boy from a coal-mining town who once herded cows and cleaned engines could one day help shape the modern world. I hope students like you remember that innovation doesn’t always come from privilege or fame—it often begins with curiosity, grit, and the courage to believe in something no one else sees yet.

And if you ever ride a train or hear the whistle of a locomotive, remember—you're hearing the echo of an idea that was once just a whisper in the mind of a coal miner's son.

The Invention of the Steam Locomotive - Told by George Stephenson

I was born into a world of coal, soot, and sweat. My father worked as a fireman for a pumping engine at the Wylam Colliery in Northumberland, and from a young age, I joined him in the engine house. The machines fascinated me—the way they hissed and groaned, how steam pushed iron to life. I couldn’t read or write until I was in my late teens, but I had a head for mechanics. I watched, I listened, and I built my knowledge bolt by bolt. By the time I was in my twenties, I was repairing engines underground and dreaming of something more. I didn’t want to just fix machines—I wanted to create them.

An Idea on Iron Rails

The early 1800s were a time of clumsy progress. We had stationary steam engines pumping water from the mines, and we had wooden or iron wagonways for hauling coal to rivers. But horses still did most of the pulling. It was slow, expensive, and inefficient. What if, I thought, we could take the power of a steam engine and set it on wheels? What if a machine could haul coal, wagons, and even people? Others had tried. Richard Trevithick had built a steam carriage that ran on rails in 1804, but it wasn’t reliable. Still, the spark had caught in my mind.

The First Steps: Blücher

In 1814, while working as the engine-wright at the Killingworth Colliery, I built my first steam locomotive. I named it Blücher, after the Prussian general who had helped defeat Napoleon. It wasn’t elegant, and it certainly wasn’t fast—it crawled along at about four miles per hour. But it worked. It pulled heavy coal wagons up steep gradients without the need for horses. That, to me, was the breakthrough. I kept building more engines, each one better than the last. I focused on traction, weight distribution, and practical performance. Most importantly, I kept learning from every flaw.

The Rocket Takes Shape

By the late 1820s, a new opportunity arose. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway was preparing to open, and they needed a locomotive capable of handling both freight and passengers. To choose the best design, they held a competition—the Rainhill Trials. My son Robert and I set to work building the engine that would become the Rocket. We designed it from the ground up with speed, power, and reliability in mind. The Rocket used a multi-tube boiler to increase steam production, a blast pipe to improve draft, and it weighed just over four tons—light compared to others.

Victory at Rainhill

In October 1829, the Rocket was put to the test at the Rainhill Trials. It outpaced all its rivals, reaching speeds of twenty-five to thirty miles per hour—a feat that had once seemed impossible. The judges and the crowd were astonished. The Rocket ran steadily, safely, and faster than any locomotive before it. The directors of the railway chose it as the standard engine, and just like that, steam locomotion was no longer a curiosity—it was the future.

A Machine That Changed the World

The Rocket became the model for nearly every steam locomotive that followed. Its design principles were adopted worldwide. But the invention of the locomotive wasn’t just a technical achievement—it was a social one. It connected towns, shrunk distances, and made time itself feel faster. It brought opportunity to people who had never traveled beyond their own village. It carried mail, food, and raw materials with a speed that transformed industry.

Looking Back

When I first pieced together the Blücher, I never imagined how far steam locomotion would go. I only saw a problem that needed solving and a tool that could make life better. I wasn’t born to wealth or education, but I had my hands, my eyes, and a determination to make engines move. The Rocket was my proudest creation, not because it made me famous, but because it proved that a simple man with a stubborn mind could change the course of human travel.

So if you ever hear the whistle of a train, know that it started with an idea—an idea born in a coal mine, hammered together in a small workshop, and fired into life by steam and vision.

Building the First Railway Networks - Told by George Stephenson When I first began working in the coal mines, transport was a slow and grueling affair. Horses hauled wagons along wooden rails, creaking and dragging their loads across uneven paths. It was inefficient, expensive, and maddeningly slow. But I saw promise in something better—iron rails, powered not by horses, but by steam. My early locomotive designs proved that it was possible. But to truly change the way the world moved, we needed more than just an engine. We needed a network—a railway that connected people, products, and places. And we had to build it from nothing.

The Stockton and Darlington Railway

In the early 1820s, a group of investors from northeast England came together with a bold plan: to create a railway that would connect the coalfields near Shildon with the port town of Stockton-on-Tees. They hired me as their chief engineer. This would become the Stockton and Darlington Railway, and it would be the first public railway in the world to use steam locomotives. But the road ahead was rough—literally and figuratively.

The landscape was no easy thing to conquer. We had to survey miles of land, convince farmers to give up their fields, and navigate uneven ground, swamps, and streams. I had to make decisions about gradients, curves, and bridges—all while making sure the new iron rails would hold the weight of my locomotives. Many doubted the whole endeavor. People said that steam engines were too dangerous, too heavy, or too strange. They thought only horses could be trusted.

But on September 27, 1825, we proved them wrong. My locomotive, Locomotion No. 1, pulled both coal and passengers along twenty-five miles of iron track. Crowds gathered to witness it. For the first time, people rode behind a machine, not a horse. The age of steam had arrived.

Liverpool and Manchester: A New Challenge

Though the Stockton and Darlington line was a success, it served mostly freight. The next great challenge came when merchants and manufacturers pushed for a line between Liverpool and Manchester. These were two of the most important industrial cities in England—Liverpool for its shipping and Manchester for its textile production. Connecting them by rail would transform trade, but the job would test every skill I had.

The terrain between Liverpool and Manchester was difficult, especially the section known as Chat Moss—a vast, boggy marshland that threatened to swallow up any structure placed upon it. Many engineers told me it couldn’t be done. But I believed otherwise. Using thousands of bundles of heather, wood, and tar, we floated the track on top of the bog. Bit by bit, we built a stable surface strong enough to support locomotives.

There were other obstacles, too. We needed bridges, tunnels, cuttings, and embankments. We had to invent new techniques, train workers, and fight constant delays and doubts. But I pushed forward, day by day, solving each problem as it came.

The Rainhill Trials and the Rocket

Before the railway opened, the directors of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway announced a competition: they would choose the best locomotive from several inventors. That’s when I unveiled the Rocket, a locomotive designed by me and my son Robert. It was faster, lighter, and more efficient than anything we had built before. At the Rainhill Trials in 1829, the Rocket blew away the competition, reaching speeds over twenty-five miles per hour.

That victory wasn’t just a personal triumph—it sealed the future of rail travel. The directors adopted the Rocket, and the railway officially opened in 1830, carrying both freight and paying passengers. It was the first modern railway in every sense.

A Nation Transformed

What we built wasn’t just a railway. It was a new way of life. Goods traveled faster. People moved between cities in hours instead of days. Entire industries reorganized around the railways. Farmers could sell fresh produce in distant towns. Workers could commute. Even time itself changed—railways forced the creation of standardized timekeeping across regions.

But it hadn’t been easy. We faced every sort of obstacle—technical, social, and financial. People feared the speed. They feared explosions. They feared change. But slowly, as they watched trains roar across the countryside, even the doubters began to believe.

Why It Matters

I didn’t have formal schooling. I didn’t come from wealth. But I believed in hard work, steady hands, and the power of innovation. Building the Stockton and Darlington and the Liverpool and Manchester railways took more than engineering. It took courage, persistence, and the will to do something the world had never seen before. And in doing so, we laid the tracks not just for trains—but for the future.

My Name is Robert Fulton (1765–1815): The Developer of the First Real SteamboatI was born in 1765 in a quiet town in Pennsylvania, before the United States even existed. Back then, we were still British colonies, and life was simple but tough. My father was a hardworking man, though we had little money, and when he died, I was only a boy. Even so, I found joy in sketching and tinkering. I loved to draw, paint, and explore how things worked. While other children might have dreamed of becoming soldiers or farmers, I was already dreaming of machines—how they could be made better, faster, and more useful.

A Young Artist with Big Ideas

As a teenager, I started working as a painter. I was good enough to earn a living, painting miniature portraits and landscapes for people in Philadelphia. I saved my earnings and even bought a farm for my mother. But even as I painted, my mind stayed busy with inventions. I created mechanical tools, experimented with waterwheels, and dreamed of ways to make travel easier. I wanted to understand not just how to make something look beautiful—but how to make something work.

Across the Sea for Opportunity

In 1787, I sailed to England to study art, but soon my interests shifted. I met inventors, engineers, and entrepreneurs, and their energy was contagious. I began to focus on engineering, especially things that moved—boats, canals, and machinery. One of my earliest projects was designing a system for improving canals, which were vital for trade. Later, in France, I worked on something even more daring: a submarine. I called it the Nautilus. It was a metal vessel that could dive underwater—imagine that! Though it didn’t win widespread support, it was a step forward in thinking differently about transportation.

A Dream of Steam on Water

Through all my travels and experiments, one idea kept coming back to me: using steam power to move a boat. Many had tried before, but none had made it truly work on a large scale. When I returned to America in 1806, I partnered with Robert Livingston, a wealthy and influential man who believed in my dream. We built a steamboat and called it the Clermont. Most people laughed at it. They thought it would explode, sink, or simply stall in the water. But I had confidence in my design.

The Journey That Changed Everything

In 1807, we launched the Clermont on the Hudson River. It traveled from New York City to Albany, cutting the journey to just over thirty hours. People along the riverbanks watched in awe as the strange vessel puffed smoke and paddled upstream—without sails, without horses. It was a miracle to them. To me, it was the future. That voyage didn’t just prove my critics wrong—it opened a new chapter in American transportation.

Spreading the Steam Revolution

After the Clermont, steamboats began appearing on major rivers like the Mississippi and the Ohio. Suddenly, goods could move faster and farther. Farmers in the Midwest could ship crops to cities. People could travel great distances without relying on wind or muscle. I continued to improve my designs and expand operations, helping turn America’s vast rivers into highways of industry and opportunity.

What I Leave Behind

I passed away in 1815, just as the steamboat era was beginning to boom. I didn’t get to see how far steam travel would go—how it would connect continents and shape economies. But I knew something important had changed. My steamboat had helped make the world a smaller, faster, more connected place.

If there’s anything I hope you take from my story, it’s this: don’t be afraid to try what others say is impossible. My success wasn’t just built on knowledge—it was built on persistence, on believing in an idea and chasing it through failure, through mockery, through doubt. Invention is rarely easy, but it’s always worth it.

The Steamboat and the Age of River Travel: Told by Robert Fulton Ever since I was a boy growing up along the streams and rivers of Pennsylvania, I had watched boats struggle upstream, crews sweating against the force of nature. Downstream was easy, but coming back up was another story entirely. It seemed absurd to me that a country so rich in rivers should be so dependent on wind, current, or manpower. As I grew older and traveled abroad, I saw how steam was beginning to change everything—powering factories, pumping water, even driving primitive land vehicles. I believed steam could conquer the river, too. But believing and building are two very different things.

From Canals to Engines

In Europe, I first explored the world of engineering through canal improvements and submarine designs. I was always fascinated by how people and goods could move more efficiently. But it wasn’t until I returned to America in 1806, filled with ideas and determination, that I truly committed myself to creating a steamboat that could work—not just once, not just in theory, but every day, up and down America’s mighty rivers. I partnered with Robert Livingston, who had a monopoly to operate steam vessels in New York waters. He believed in my vision, and more importantly, he had the resources to support it.

Building the Clermont

We began our great project on the East River. I designed a long, narrow hull to reduce resistance and adapted a Watt-type steam engine to power paddle wheels mounted on either side of the boat. I named her the Clermont, though some referred to it mockingly as “Fulton’s Folly.” She was clunky, loud, and strange to look at, and many doubted she’d survive her first trip. I was used to skepticism. I focused on the mechanics, making sure every bolt was tight, every wheel balanced, every paddle synchronized.

The Maiden Voyage

In August of 1807, we launched the Clermont on the Hudson River. From New York City, we steamed north toward Albany. As the vessel began to churn upriver, crowds gathered along the banks, pointing and staring. Some cheered, others crossed themselves in fear, and many simply watched in disbelief as smoke rose from the funnel and the boat pushed steadily against the current. We made the journey in just over thirty hours—a time so fast, so consistent, that it turned heads and opened eyes.

Opening the Rivers

That first voyage was more than a personal victory. It proved that steam-powered navigation could work not just in theory, but in business. Soon after, we launched regular service between New York and Albany. The Clermont could carry passengers and freight both ways, and it wasn’t dependent on the whims of wind or the exhaustion of horses. This was the key. Rivers became highways, open in both directions, and communities along the banks began to thrive. Farmers could get their goods to market faster. Travelers could reach distant towns without hardship. The steamboat shrank the country and expanded opportunity.

A New Era of Motion

After the success of the Clermont, steamboats multiplied. They spread down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, carrying cotton, wheat, and people through the heart of the young nation. What had once taken weeks could now be done in days. Cities like New Orleans, St. Louis, and Cincinnati grew rapidly, fueled by this new mobility. The economy boomed. Steam didn't just power boats—it powered ambition.

Why It Mattered

I wasn’t the first to imagine steam on water, but I was the first to make it work in a way that the public could depend on. That made all the difference. Invention is not just about discovery—it’s about usefulness. The Clermont didn’t just break through the river’s current—it broke through old ways of thinking. And it did so not with a bang, but with steady pistons and spinning paddle wheels.

If you live in a world where travel feels instant and goods arrive overnight, you’re living in a world that began with steam on the Hudson River. A world where an idea, once mocked, became a movement. That was the promise I saw in the water, and I’m proud to say I helped it come to life.

Transportation and the Expansion of the American Frontier - Told by Robert

When I was a boy, America was a narrow string of colonies hugging the Atlantic. But after independence, something shifted. People wanted to move—westward, inland, away from the crowded coast and toward opportunity. The land was vast and rich, but there was one major obstacle standing in the way: how to get there, and how to stay connected once you did. Roads were poor, wagons were slow, and rivers only helped if you were going with the current. What this young nation needed was a way to travel both directions—quickly, reliably, and affordably. And that’s where the steamboat came in.

The Rivers as Arteries

The Mississippi and Ohio Rivers were like great highways flowing through the interior. They touched the edges of fertile farmland, small towns, and new settlements. But before steamboats, moving upriver was a nightmare. Flatboats could float down with ease, but the return journey meant dragging vessels back by hand or animal—or simply abandoning them and building anew. That was inefficient, costly, and slow. I believed that steam power could reverse the flow—not of the water, but of the economy. If we could move people and goods upstream as easily as down, then the frontier wouldn’t feel like the edge of civilization anymore—it would feel like the center of it.

Steamboats Change the Game

Once the Clermont proved steam navigation worked on the Hudson River, others took up the challenge and brought the same idea to the western rivers. Within a few years, steamboats were puffing smoke and turning paddle wheels up and down the Mississippi and its tributaries. Suddenly, what had once been distant wilderness was connected to major cities like New Orleans, Louisville, and Pittsburgh. Farmers could ship grain, pork, and cotton downstream to market, and merchants could send goods, tools, and luxuries back upstream. The flow was no longer one-way—it was balanced, dynamic, and alive.

Settlements Spring Up

Every time a steamboat stopped at a bend in the river, a town seemed to rise around it. Places like Memphis, Natchez, and St. Louis grew rapidly, fueled by the energy and commerce the riverboats brought. People followed the promise of trade and opportunity. Land that had once taken weeks or months to reach could now be accessed in days. The steamboat didn’t just help settlers get to the frontier—it helped them stay there, build businesses, and stay connected with the rest of the country.

A Moving Nation

The effect on migration was profound. Whole families packed up and moved inland, knowing they wouldn’t be isolated. Riverboats made it possible to ship furniture, tools, and even building materials. More importantly, they brought news—newspapers, letters, travelers—all helping new communities feel less like outposts and more like part of a growing nation. The frontier began to shrink, not in size, but in distance. The steamboat had made the vast land feel more manageable.

Bridging the Coasts and the Interior

Eventually, steamboats became a link between inland towns and coastal cities. Goods from the Midwest traveled down the Mississippi to New Orleans and were then loaded onto ocean-going ships bound for New York, Boston, or even Europe. Cotton from Southern plantations, flour from Ohio mills, and pork from Kentucky farms—all made their way to global markets because steam engines pushed their way through the heart of America.

A Legacy of Connection

I may have launched my first boat on the Hudson River, but its ripple traveled far beyond. I didn’t set out to open the frontier—I simply wanted to solve a problem. But that’s the power of invention. When you give people a new way to move, to reach, to communicate—they will transform the world with it. The steamboat turned rivers into roads, wilderness into communities, and dreams into destinations. And though I didn’t live to see the full expansion of the American frontier, I’m proud to know that I helped make it possible, one paddle wheel at a time.

My Name is Cornelius Vanderbilt: The Commodore - Transportation TycoonI was born in 1794 on Staten Island, New York. My family wasn’t wealthy—we were farmers and boatmen. My father ferried goods across New York Harbor, and I started helping him when I was just a boy. I didn’t care much for books, and I only had a few years of formal schooling. But what I lacked in education, I made up for with ambition. By the time I was sixteen, I convinced my mother to loan me one hundred dollars to buy my own sailboat. I ferried passengers and cargo between Staten Island and Manhattan. People began to call me “The Commodore,” and the name stuck for the rest of my life.

Mastering the Waterways

In my early years, I worked on the water—sailing, hauling, and building a reputation for being fast, reliable, and ruthless in competition. I wasn’t afraid to undercut my rivals or work long hours. When steamboats started appearing, I saw the future and jumped in. I partnered with Thomas Gibbons and ran steamboats along the Hudson River and between New York and New Jersey. At that time, monopolies controlled much of the steamboat business, but I fought those monopolies—and won. A famous court case, Gibbons v. Ogden, broke open steamboat trade for everyone. That victory was bigger than just my own gain. It set a national precedent for free competition in commerce.

Building an Empire of Steam

Once I had a foothold in steamboats, I expanded fast. I ran boats on the East Coast, around Florida, and through the Gulf of Mexico. I even created a route across Nicaragua to carry passengers and gold seekers to California faster than anyone else could. People needed to move—and I figured out how to move them cheaper and quicker than anyone else. I never cared much for frills. My boats weren’t always the prettiest, but they got the job done. That’s what mattered to me.

Shifting From Water to Iron

As I got older, I saw the tides changing again—this time from steamships to railroads. By the 1850s, I started selling off my shipping interests and investing in rail. Many thought I was crazy, giving up the business I had dominated for decades. But I had learned to watch where the world was going, not where it had been. I bought up key rail lines, especially in the Northeast. In 1867, I took control of the New York Central Railroad and began building a network that stretched west toward Chicago.

Making Railroads the Backbone of America

I didn’t just buy railroads—I improved them. I introduced standard rail gauges so trains could run on the same tracks. I built the Grand Central Depot in New York City, a hub of activity that brought rail travel into the heart of Manhattan. My rail system connected cities, boosted trade, and helped knit the nation together after the Civil War. I believed in efficiency, speed, and cutting waste. Those ideas helped me create one of the most powerful and profitable transportation empires in the world.

The Power and the Price of Wealth

By the time I died in 1877, I was one of the richest men in American history. I was never much for charity during my lifetime. I believed that if you wanted something, you earned it. I lived by that creed. But I did leave a gift of a million dollars to found Vanderbilt University in Tennessee. I hoped it would help rebuild and educate the South after the war. Some say I was too harsh, too greedy, too rough. But I built from the bottom up. I didn’t inherit my success—I forged it, with my hands, my instincts, and an iron will.

What I Hope You Remember

If you take anything from my story, let it be this: don’t wait for someone to hand you a path. Make your own. The world rewards those who work, who adapt, who dare to move faster and think ahead. I started with a boat and a borrowed hundred dollars. I ended with a railroad empire that changed how America moved. That kind of journey is still possible—if you’re ready to work for it.

From Steamboats to Railroads: Business Revolution - Told by Cornelius Vanderbilt

When I was a boy working on my father’s ferry in New York Harbor, I never imagined I’d one day control thousands of miles of track. Back then, I just wanted to work hard, earn my keep, and get ahead. My first real step came when I borrowed a hundred dollars from my mother and bought a small sailing vessel. That little boat started it all. I learned the tides, the trade, and the value of beating the other guy by being faster, cheaper, and tougher. When steam came along, I jumped in early and never looked back. I ran steamboats up and down the Hudson, then expanded to Long Island Sound and the coastal routes, out-competing every rival in sight.

Crushing the Competition

I didn’t just run steamboats—I ran the business like a war. I slashed prices, improved schedules, and made my ships faster and more reliable. If a competitor tried to undercut me, I’d cut my fares so low they’d bleed money until they gave up or sold out. People called me ruthless. I called it smart. I made travel and shipping cheaper for the public and brought order to a chaotic system. By the 1840s, I had made millions on water. But I wasn’t interested in coasting. I kept my eye on the horizon, and I saw the future—iron rails stretching across the land.

The Shift to Steel and Steam

At first, I didn’t trust railroads. They seemed fragile, experimental, and full of schemers. But by the 1850s, it was clear that trains were going to move people and freight faster and farther than steamboats ever could. So I made my move. I started selling off my steamship lines and began buying up stock in railroads. Not just any railroads—the important ones. I bought controlling interests in the New York and Harlem Railroad, then the Hudson River Railroad, and eventually the New York Central. I wasn’t playing games—I was building a network.

Forging an Empire

Railroads were the arteries of the new American economy. They linked factories to markets, farms to cities, ports to inland towns. I focused on consolidation—combining small, inefficient lines into a single, powerful system. I standardized gauges, improved tracks, and built better stations. I made it possible to ship goods from the Great Lakes to New York Harbor without changing trains. Every improvement cut costs, boosted speed, and made my empire more efficient. I wasn’t just building a railroad—I was building a machine that made the whole country move.

Business as Warfare

I ran my railroads the same way I ran my steamboats—with precision, aggression, and an eye on the bottom line. I kept expenses low and profits high. I didn’t waste time on luxuries or sentiment. If something didn’t work, I replaced it. If someone got in my way, I bought them out or drove them out. My competitors feared me, but my passengers and shippers trusted me. They knew I delivered. I turned transportation into a business empire, one mile at a time.

The New American Economy

By the time I finished, I had helped transform the U.S. economy. Goods that once took weeks to move could now travel in days. Prices dropped. Cities grew. Small towns gained access to national markets. The cost of moving a barrel of flour, a ton of coal, or a family of five became affordable. Railroads didn’t just carry people—they carried dreams, money, and power. And behind many of those trains was a man who started with nothing more than a rowboat and a plan.

Legacy of Motion

I didn’t invent the railroad, just like I didn’t invent the steamboat. But I made them work. I made them profitable. I made them permanent. That’s what entrepreneurs do—we take ideas and make them real. I helped change how America moved, how it traded, and how it grew. The tracks I laid weren’t just iron—they were lines that connected the past to the future. And I knew, even then, that we were never going back.

Railroads and the Rise of Monopolies and Corporate Power - Told by Cornelius

By the time I turned my full attention to railroads in the 1850s, I already knew how to outwork and outsmart my competitors. I had done it on the water with steamboats, and now I was ready to do it on land. But the railroad business wasn’t just about engines and tracks—it was about control. At first, there were dozens of small, disconnected railway companies, each with their own tracks, rules, and leadership. That didn’t make sense to me. A system is only as strong as its weakest part. I believed the future belonged to those who could consolidate, unify, and dominate.

Swallowing the Lines

I started buying. Small railroads. Medium-sized railroads. Struggling railroads with old equipment and poor service. I didn’t just want pieces—I wanted whole corridors. I took over the New York and Harlem Railroad, then the Hudson River Railroad. After that came the crown jewel: the New York Central. One by one, I pieced them together into a single, powerful system that stretched from the Atlantic coast to the Great Lakes. People called it a monopoly. I called it efficiency. With every line I absorbed, I lowered operating costs, shortened travel times, and simplified shipping for businesses across the country.

Crushing the Rate Wars

But consolidation wasn’t always peaceful. When competitors tried to undercut me with lower freight rates, I fought back. I slashed prices to the bone—sometimes even ran routes at a loss—just to drive them out. These battles were called rate wars, and they were brutal. But I had deep pockets, and I could afford to lose a little now to gain a lot later. Once my rivals gave up or sold out, I raised rates just enough to make a tidy profit, but never so high that my customers would rebel. I played the long game, and I rarely lost.

The Birth of Corporate Power

What we were doing wasn’t just building railroads—we were creating a new kind of business. The railroad corporations were bigger, richer, and more organized than anything America had ever seen. We hired thousands of workers, managed fleets of locomotives, and kept precise timetables that governed the rhythms of entire cities. The scale of it all required new methods: formal accounting, centralized offices, legal departments, and boards of directors. It wasn’t just transportation anymore—it was corporate management, and we were writing the rules as we went.

Fueling the Industrial Machine

Our rail lines fed the factories, hauled raw materials, and delivered finished goods. Coal from Pennsylvania. Steel from Pittsburgh. Grain from the Midwest. It all flowed along the tracks we laid. The railroads didn’t just serve the Industrial Revolution—they powered it. And in return, industrialists invested in us, rode our trains, and shipped their products through our depots. It was a system built on mutual gain—and mutual dependence. If the railroads stopped, the entire economy froze.

The Cost of Power

I won’t pretend there weren’t consequences. Smaller towns sometimes suffered when we bypassed them or charged too much for short-haul freight. Farmers complained that big railroads squeezed them dry. Newspapers called us “robber barons.” And yes, we got rich—staggeringly rich. But we also built the arteries of a modern economy. We didn’t inherit our power. We built it with iron, sweat, and an iron will.

Legacy of the Iron Network

I died in 1877, but the empire I built rolled on. The federal government would eventually step in, regulating rates and watching for abuses. Other tycoons would follow—Carnegie in steel, Rockefeller in oil. But the model began with us, the railroad kings. We taught the country that scale meant strength, and that control meant survival. So when you hear the word “monopoly,” remember—behind it is a story of vision, risk, and the drive to knit a sprawling young nation into one connected machine. That was my legacy. That was the age we built.

My Name is Mary Walton: Inventor Who Reduced Pollution

I was born in the 1800s, in a time when women were expected to stay quiet, raise children, and leave invention to the men. But that never sat right with me. I wasn’t born into wealth, nor was I given the kind of education that boys received. Still, I paid attention. I listened to the city, to its people, and to the way machines moved and disrupted the world around us. I lived in New York City, and every day I watched it grow taller, louder, and dirtier. Where others saw progress, I also saw problems—especially problems no one else seemed to care enough to fix.

Living Above the Chaos

My apartment sat above an elevated railway, one of the many that were multiplying across Manhattan. The noise was unbearable. Every time a train passed, the windows rattled, the floor trembled, and conversations had to stop. It wasn’t just an inconvenience—it was a disruption to daily life for thousands of people. While most just accepted it or moved away, I decided to do something about it. I didn’t have a lab or a team of engineers. I just had a problem and a determination to solve it.

Inventing a Quieter City

In 1881, I designed a system to reduce the noise of elevated railway trains. I studied how sound and vibration traveled through iron and wood. Then, using simple tools and clever thinking, I created a sound-dampening system that used wooden boxes lined with sand to absorb the vibration. It worked. The roar of the trains became a low rumble. I brought my design to the Metropolitan Railroad Company. They were skeptical at first—after all, I was a woman without formal credentials. But when they tested it, they saw that it worked, and they adopted my invention for their elevated railways.

Fighting Factory Pollution

Noise wasn’t the only problem I took on. I also noticed how factory smokestacks were pumping endless clouds of soot and smoke into the air. It coated buildings, filled lungs, and darkened the skies. The Industrial Revolution had brought progress, yes—but at a cost to the environment and public health. I developed a device that diverted factory emissions through water tanks, scrubbing the pollutants before they reached the air. This invention became one of the earliest forms of pollution control in American cities.

Recognition Without a Spotlight

I didn’t invent for fame or fortune. In fact, very few people knew my name at the time. There were no grand parades or newspaper headlines. Being a woman inventor in the 19th century meant working twice as hard for half the credit. But I patented my designs, and they made a real difference. Elevated trains became quieter. The air above factories became cleaner. My work helped city life become more livable during a time of explosive industrial growth.

Why I Spoke Up

I wasn’t wealthy or powerful, but I believed I had the right to improve the world around me. I believed women had minds just as capable as any man’s. I believed in action—quiet, steady, determined action. You don’t have to be loud to be heard. You just have to speak through your work, and make sure your work works.

What I Leave for You

If there’s something I’d like you to remember, it’s this: pay attention. The world is full of noise—both the kind you hear and the kind that comes from people saying “that’s just the way things are.” But if something isn’t right, and you think you can fix it, then try. Don’t wait for permission. Don’t assume someone else is smarter or better suited. Whether you're a student, a teacher, an inventor, or a dreamer—your ideas matter. They can build, protect, and heal. Mine did. And so can yours.

The Hidden Costs of Industrial Transportation - Told by Mary Walton

I lived in New York City during a time of incredible change. Trains thundered overhead, factories belched smoke day and night, and people called it progress. And in many ways, it was. The railroads connected distant cities, steamboats brought goods up the rivers, and factories ran on the fuel of invention. But beneath all the excitement, there were problems no one wanted to talk about. I didn’t read about them in newspapers or hear them discussed by engineers in public forums. I heard them through my walls, through my windows, through the floors of my apartment that shook each time an elevated train passed by.

Noise That Shook the Bones

The first time I heard the elevated railway run over our street, I was startled. But it didn’t stop. Day after day, hour after hour, trains clattered above our heads like iron monsters. The windows rattled, the dishes trembled, and conversation was impossible while the cars passed. Sleep was hard to come by. Peace was harder still. People tried to get used to it, but it wore us down. It wasn’t just the noise—it was the relentlessness of it. And yet, when I raised the issue, most men in power shrugged it off. They said, “That’s the price of progress.”

Air That Turned the Sky Gray

Then there was the smoke. The factories powered by coal and the trains fueled by fire left thick trails in the sky. Soot settled on windowsills. It blackened the bricks of every building. On some days, the sky turned gray before noon. People walked the streets with handkerchiefs over their faces. Children coughed. The poor, who couldn’t afford to move away, suffered most. And still, the city kept building higher, laying more tracks, lighting more fires. The more transportation advanced, the more pollution seemed to follow it. But who would stop it? No one—not unless someone dared to speak up.

A City Under Siege

What most people didn’t see was that the growth of transportation came at a cost to daily life. The city was transforming, but it wasn’t always for the better. Entire neighborhoods were reshaped by rail lines. Sunlight was blocked by train structures. The constant rumble of steel wore people thin. New York had become a marvel of movement, but it was also becoming a place where it was hard to breathe, hard to think, and hard to rest. Progress was loud, and no one had planned for its impact on the people who lived beneath it.

One Voice, One Invention

I wasn’t a trained engineer. I wasn’t a wealthy industrialist. I was a woman with a window that shook too often. But I believed that someone had to do something. So I studied sound. I watched how vibrations moved through metal and wood. I built a prototype—a noise-reduction system that absorbed the shock and sound of the trains above. And it worked. The elevated rail company didn’t laugh when they saw the results. They implemented my invention because it made life better. Not just for me, but for every family living beneath the tracks.

What I Saw Then

The machines that moved America forward were miracles, but they cast long shadows. Pollution, noise, and overcrowding were not just side effects—they were consequences. And if we ignored them, they would grow worse. I didn’t want to stop progress. I wanted to shape it. I wanted cities to be cleaner, calmer, and more humane—places where people could live and thrive alongside the engines that powered the age.

Why It Still Matters

The hidden costs of industrial transportation are lessons we still need to remember. Every invention, no matter how exciting, affects more than just the bottom line. It affects the air we breathe, the streets we walk, the health of our children, and the quality of our lives. I didn’t invent a locomotive or build a railway, but I made the world a little quieter, a little cleaner. And that, to me, was just as important. Because true progress doesn’t drown people out—it listens to them.

Innovations in Pollution Control and Urban Adaptation - Told by Mary Walton

In the bustling heart of New York City, I lived close enough to feel the city’s pulse—its trains, its factories, its endless noise. For some, that clatter and smoke were symbols of progress. But for people like me, who lived just above the streets and rails, they were reminders of everything that was overlooked in the rush to industrialize. The men who built the machines and owned the factories rarely had to live with the consequences. But I did. So did mothers, children, shopkeepers, and laborers. That’s why I decided to act—not because I had money or formal education, but because I had to live with the problem.

Women as Problem-Solvers

I didn’t do this work for applause, and I didn’t do it alone. Across the country, other women were solving problems every day. We didn’t always have access to the tools or laboratories that men did, but we had kitchens, workshops, and sharp minds. We adapted our surroundings out of necessity. Some women improved cooking stoves to reduce fuel use. Others designed better ways to heat homes, light streets, or preserve food. We weren’t often recognized, but we were always innovating—quietly, persistently, creatively. Just because our names weren’t printed in textbooks didn’t mean we hadn’t helped shape the world.

Changing the City from Within

My goal was never to stop progress. I believed in industry, in invention, in the future. But I also believed in making that future livable. A city must be more than efficient—it must be humane. That’s why I focused on solutions that could be built into the fabric of the city without tearing it down. Noise reduction didn’t mean halting trains. Pollution control didn’t mean closing factories. It meant adapting, refining, and respecting the people who lived alongside progress.

A Lasting Message

If there’s anything I want remembered, it’s that innovation isn’t always about creating something grand or new. Sometimes it’s about noticing a problem, rolling up your sleeves, and fixing it in a way that makes life better for others. You don’t need a title or a lab coat to be an inventor. You need eyes that see clearly, hands that work steadily, and the courage to believe your ideas matter. Because they do. They always have.

The Global Legacy of the Transportation Revolution – Told by George Stephenson, Robert Fulton, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and Mary Walton

George Stephenson stood by the window of the meeting hall, hands folded behind his back as he gazed out at a passing train. “I never imagined,” he said quietly, “that an engine like the Rocket would help change the very shape of the world.” He turned to face the others—Robert Fulton, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and Mary Walton—each of them bearing the marks of a life spent reshaping the rhythms of travel and industry. “We didn’t just make machines,” Stephenson continued. “We made people move. That was the start of something far larger than any one of us.”

Bridging Continents and Communities

Robert Fulton nodded, his expression thoughtful. “When I launched the Clermont, I was just hoping to make river travel easier between Albany and New York. But once steam proved itself, it became the thread that wove together entire regions. Suddenly, rivers weren’t barriers—they were corridors. And that same idea spread everywhere. From the Mississippi to the Nile, steamships shrank the world. Goods arrived faster. Letters reached loved ones in days, not weeks. Farmers in Ohio could feed cities in the East. Traders in America could reach markets across the Atlantic.”

The Rise of Global Trade and Empires

Cornelius Vanderbilt leaned forward in his chair, arms resting on his knees. “And it didn’t stop at rivers,” he added. “Railroads took over where the water couldn’t go. Steel tracks crossed deserts, climbed mountains, and cut through forests. They didn’t just move freight—they moved frontiers. Nations got bigger. Cities got richer. Trade exploded because you could move cotton from Georgia to New York in less time than it used to take to go across town. Then it sailed out to England, to France, to India. That’s what created the real global economy. Transportation wasn’t just part of it—it was the engine behind it all.”

The Price of Progress

Mary Walton listened quietly, then cleared her throat. “It’s true,” she said, “we connected the world. But we also lit the fires that came with it—literal fires in engines, factories, and smokestacks. As cities grew busier and the economy grew faster, the skies grew darker. The noise grew louder. The air grew heavier. The transportation revolution made life easier, yes—but it also made life harder in ways people didn’t notice until the damage was already being done. And the people who felt it most weren’t always the ones profiting from it.”

Migration and Human Possibility

Stephenson nodded in agreement. “Still,” he said, “I watched men and women climb aboard trains for the first time and travel to places they never thought they’d see. The poor could leave dying farms and find work in cities. A boy could take a train to school. A woman could open a business in a town she’d never been to. The very idea of distance changed. And with that, so did people’s understanding of what was possible.”

Fulton added, “And don’t forget the immigrants. Steamboats brought them by the tens of thousands—Irish, German, Chinese, Italian. Some came to escape hardship. Others came chasing dreams. They built railroads, they worked docks, they opened shops. We didn’t just transport goods—we transported hope.”

An Inheritance of Connection

Vanderbilt leaned back and folded his arms. “We made the world smaller,” he said. “And faster. And louder. We didn’t always get it right, but we built something that outlived us. The transportation networks we started still carry people and ideas across continents. They connect families. They fuel economies. They keep the world spinning.”

Mary Walton looked around at the others. “But the next generation has to remember: speed isn’t everything. Efficiency must walk hand-in-hand with responsibility. If we taught the world how to move, they must also learn when to slow down—when to listen, when to care.”

Looking to the Tracks Ahead

The room fell quiet for a moment. Outside, another train passed—quieter now, smoother, powered by electricity and guided by systems none of them could have imagined in their own time. Yet they each knew, in their hearts, that it had all begun with their labor. With paddle wheels and pistons, rails and rivets, questions and courage. The Transportation Revolution had not only changed how the world moved—it had changed what the world was. And the legacy of that movement would continue, wherever there were people who dared to make the world smaller, more connected, and more just.

Rate Discrimination and the Farmers’ Revolt – Told by George and Cornelius

George Stephenson stood by the edge of the platform, eyes scanning the quiet countryside beyond the tracks. “It’s a strange thing,” he said, turning to Vanderbilt, “to see how something born from invention and hope could turn into a source of frustration and fury for so many.” Cornelius Vanderbilt, older now, leaned on his cane and gave a dry chuckle. “We didn’t build the railroads to make people angry, George. We built them to make money—and to move the world. But I admit, in America, things got... complicated.”

The Short Haul Dilemma

Stephenson looked puzzled. “I’ve read about it—the farmers, the freight rates. What went wrong?” Vanderbilt sighed. “In the early days, we charged by distance. That made sense. But over time, we learned that the real money was in volume and competition. So we cut special deals for the big shippers—grain merchants, meat packers, oil barons. They got bulk rates over long distances. But the small farmers, the ones shipping their produce from just one town to the next, they paid more per mile. Much more.”

Stephenson’s brow furrowed. “You charged more for moving something less far?” Vanderbilt nodded. “That’s right. It cost us nearly the same to handle short hauls, but we had no incentive to make them cheaper. There were fewer customers, no competition in those towns, and the bigger clients brought in steady profit. It was simple business—but to the farmers, it felt like betrayal.”

Voices from the Heartland

Stephenson paced slowly. “I built railways so coal could reach the ports and people could reach opportunity. But you—your empire grew so large that you couldn’t even hear the voices of those you passed by.” Vanderbilt didn’t argue. “They made themselves heard soon enough. In the Midwest—Illinois, Iowa, Wisconsin—they banded together. Called themselves the Grangers. Farmers, mostly. Ordinary folks who were tired of being squeezed.”

“They wanted justice,” Stephenson said quietly.

“They wanted fair rates,” Vanderbilt replied. “They said the railroads were public highways in private hands. And they weren’t wrong. We controlled the prices, the access, even which towns would thrive or fade. If a grain elevator wasn’t near a mainline, your harvest meant nothing. You couldn’t sell without going broke.”

The Granger Laws and the Pushback

Stephenson asked, “So what did they do?” Vanderbilt leaned on the railing. “They fought us with laws. In the 1870s, states like Illinois passed the Granger Laws—regulations to set maximum freight rates. Of course, we challenged them in court. We argued the states had no right to interfere with interstate commerce. Some judges agreed with us. But the battle kept growing.”

“And the government stepped in,” Stephenson added.

“In time,” Vanderbilt said. “In 1887, a decade after my death, Congress passed the Interstate Commerce Act. It created a commission to monitor railroads. The goal was fairness—no more rate discrimination, no more secret rebates for the powerful. It was the first real federal regulation of private industry in America.”

A System Rebalanced

Stephenson nodded slowly. “In Britain, we had similar calls for reform—especially when passengers and coal merchants felt they were at the mercy of railway barons. But it’s the scale of your system, Cornelius, that magnified the harm. You didn’t just carry freight. You carried power.”

Vanderbilt didn’t deny it. “And that power needed watching. I built a machine that moved the nation, but I never claimed it was perfect. Maybe we needed people like the Grangers to remind us that no machine, no matter how grand, should grind down the people who depend on it.”

Lessons on the Rails

The two men stood in silence as a train passed in the distance, its whistle soft on the wind. Stephenson turned to Vanderbilt. “Do you regret it?”

“I regret that we didn’t listen sooner,” Vanderbilt said. “But I don’t regret building the lines. I only wish we’d seen the people on both ends—not just the profits in between.”

Stephenson nodded. “Then maybe the next generation will build not only with iron and fire—but with fairness, too.”

Monopoly Power and Antitrust Backlash - Told by George Stephenson

When I first imagined steam engines running on iron rails, I didn’t see power or politics—I saw progress. I saw miners in Northumberland hauling coal more easily, farmers bringing crops to market without delay, and families traveling safely between towns. The railway, to me, was a great equalizer, a way to bind people together across space and time. But as the world adopted our machines and built vast networks of steel, something else began to form alongside the tracks—a hunger not just for movement, but for control.

From Innovation to Domination

In the early days, railways were built by many small companies, each one linking town to town, mine to mill. But in America especially, men like Cornelius Vanderbilt saw a different vision. He didn’t just want to build a railway—he wanted to own all the railways that mattered. He bought up smaller lines, standardized gauges, and turned disjointed paths into one powerful artery of trade and travel. In doing so, he created an empire. There’s no doubt he improved efficiency, but there’s also no doubt that this consolidation strangled competition.

Choking Out the Rivals

When a single company controls the only route between two cities, what choice does a merchant have? If a farmer wants to ship grain to market, he must accept the rate given—or let his harvest rot. That was the dilemma millions faced. Rates were set not by fairness or demand, but by the needs of a growing monopoly. Discounts were handed to the powerful, while the small producers paid full fare. And should a new company dare to challenge the monopoly, the old giants would slash their prices until the newcomer collapsed, then quietly raise them again.

The People Push Back

It wasn’t long before the public grew restless. Small businesses, farmers, and entire communities began to see the railroads not as a tool for growth, but as a noose around their economies. Politicians took notice. In Britain, we had earlier debates about government control and fair access, but it was in the United States where things boiled over. Angry voices rose in newspapers and in Congress. The people demanded laws that would stop the giants from crushing the weak.

The Sherman Antitrust Act

Though I did not live to see it, the storm finally broke in 1890 with the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act. It was the first major law in the United States designed to curb the power of monopolies. For the first time, the government declared that it had a duty to protect competition and prevent the abuse of corporate power. It didn’t dismantle the railroad empires overnight, but it opened the door to legal challenges. Railroad barons were dragged into court. Their deals were scrutinized. Their dominance was questioned.

Looking Back at the Tracks

I never imagined that the railway, a machine built to carry the hopes of working men and women, would become a symbol of unchecked power. But perhaps it is the fate of every great invention to carry both good and harm. When we give humans new tools, we must also give them the wisdom to use them well. The railroads brought us together—but left unchecked, they also allowed a few to rule over many.

A Caution from the Engine Room

If I could speak to the next generation of builders and dreamers, I would tell them this: It is not wrong to build, to grow, or to prosper. But it is wrong to believe that progress must come at the price of justice. Monopolies may promise efficiency, but they often deliver inequality. The railways should have served the people—not the other way around. Let the tracks we laid not only carry goods and passengers, but also carry forward the lesson that power must always be tempered by fairness.

Steam vs. Electric Power – Told by George Stephenson and Cornelius Vanderbilt

George Stephenson stood beside a silent stretch of city rail, eyes narrowed as he studied a sleek electric streetcar gliding quietly down the track. “So,” he said, half to himself, “this is what’s replaced the hiss of steam.” Cornelius Vanderbilt, leaning against a nearby lamppost, gave a short nod. “Electric power,” he said, “cleaner, quieter, and more appealing to the city folk. But it didn’t come without a fight.”

Stephenson smiled faintly. “It never does. I remember when steam was the rebellion. Now it’s steam that’s being challenged. Tell me—how did it all unfold?”

The Smoke of the City

“In the beginning,” Vanderbilt began, “steam engines were the kings of motion. My elevated railways in New York ran on steam. Powerful, proven, and built for volume. But cities started to grow tired of the noise and the smoke. Residents living beneath the elevated tracks—people like Mary Walton—complained about soot coating their homes and the thunder of locomotives shaking their walls.”

Stephenson nodded. “Steam was never gentle. It was strength and force. But I imagine cities demanded something softer.”

“They did,” Vanderbilt replied. “By the 1880s, a new technology crept in—electric traction. Streetcars powered by underground cables and overhead wires. No fire, no smoke, no ash. Just a quiet hum. And unlike steam, they could start and stop quickly, perfect for short city blocks. At first, we dismissed them. Too weak. Too new. But they improved fast.”

The Battle for the Streets

Stephenson folded his arms. “And you didn’t like the competition.”

Vanderbilt chuckled. “No one in my position ever does. The electric streetcar threatened everything we’d built. It wasn’t just a machine—it was a business model that didn’t need coal yards, water towers, or steam mechanics. The streetcar lines were cheaper to run and faster to expand. Politicians started siding with them. Property owners demanded change. And the public? They liked riding without coughing up smoke.”

“So steam was forced out,” Stephenson said.

“In stages,” Vanderbilt replied. “There were legal fights. Electric companies challenged our franchises. We tried to block them, even filed suits claiming they were unsafe. We said the overhead wires were an eyesore, a danger to horses and pedestrians. And when that didn’t work, we tried to buy them out.”

The Turning Point

Stephenson looked thoughtfully down the track. “But it didn’t stop them.”

“No,” Vanderbilt admitted. “The technology moved too quickly. By the 1890s, cities like Chicago and Boston were switching to electric streetcars. New York followed not long after. The elevated steam lines were either electrified or dismantled. And that was that. Steam stayed alive on long-distance railways, where its power still made sense. But in the city? It was outpaced.”

A Shift in Power

“So,” Stephenson asked, “was it painful to watch your empire bend to the new current?”

Vanderbilt gave a slow shrug. “It was the natural order of things. I fought for steam when it was new. Then I fought to keep it alive. But the people chose electricity, and in the end, transportation follows demand. The lesson I learned—one I imagine you knew already—is that no engine lasts forever. Not even steam.”

What It Meant for the Future

Stephenson smiled gently. “What we began with iron and fire, others carried forward with wire and light. That is the way of invention. It builds upon itself, and it leaves the old tracks behind. I suppose it’s not defeat—it’s legacy.”

Vanderbilt looked at the electric streetcar disappearing around the corner. “And as long as something’s moving forward,” he said, “we’ve done our job.”

Public vs. Private Control - Told by Robert and Cornelius

Robert Fulton sat at a wooden bench overlooking the harbor, watching ships pull in and out with rhythmic grace. Cornelius Vanderbilt joined him, the sea breeze tugging at his coat. “You know,” Fulton said, “when I built the Clermont, I thought I was opening the rivers to everyone. I didn’t imagine that one day people would be arguing whether the boats—and the railroads—should even belong to private men like us.”

Vanderbilt smirked. “They weren’t complaining when the travel was slow, dangerous, or run by amateurs. But build something efficient, make it profitable, and suddenly the public thinks they should run it themselves.”

The Rise of Private Power

Fulton nodded. “You and I—we were cut from similar cloth. I built the first steamboats. You built an empire on them. But as those empires grew, so did the complaints. People started to say the water, the rails, the streets—they weren’t just business routes. They were lifelines. And lifelines, they argued, shouldn’t be controlled by men chasing profit.”

Vanderbilt shrugged. “Profit’s what got the job done. The government didn’t build the New York Central. I did. The state didn’t lay the iron or take the risk or fight the rate wars. We invested, we innovated, we expanded. Why? Because we could earn something from it. That’s how markets work.”

The Public Pushes Back

Fulton turned slightly, his eyes on a ferry boarding passengers. “But when the small towns paid more than the big cities... when your lines refused to stop in unprofitable places... when rates favored the powerful over the struggling farmer—that’s when the people began to push back. They started asking whether essential services should ever be in the hands of men who could deny access with the stroke of a pen.”

“And yet,” Vanderbilt countered, “when government tried to step in, what did they do? They passed laws slowly. Built slowly. Spent more than they earned. You can’t run a railroad like a post office. You need bold moves, not endless committees.”

The Call for Regulation

Fulton nodded. “True, but bold moves can leave people behind. That’s why the Interstate Commerce Commission was born. It wasn’t about running your railroads—it was about watching them. Making sure you didn’t gouge the farmer while giving rebates to the oil baron. The idea wasn’t to crush innovation, but to protect fairness.”

Vanderbilt leaned back. “And once you open that door, the government walks further in. They start telling you what you can charge, where you must stop, how you must operate. Before long, the entrepreneur’s fire goes cold. Who would invest in something they can’t control?”

The Ongoing Debate

The waves slapped gently at the pier. “Still,” Fulton said quietly, “some things—bridges, water systems, transit lines—don’t function like normal businesses. They serve everyone, not just customers. Maybe there’s room for both hands—one public, one private—if they can learn to work together.”

Vanderbilt exhaled slowly. “Maybe. But it’s a fine line. Too much control and you strangle innovation. Too little, and you let monopolies rule the world. I suppose we were the proof of both extremes.”

The Argument That Never Ends

They sat in silence for a moment, watching a streetcar rattle along the tracks above the riverfront. “Do you think the debate will ever end?” Fulton asked.

“No,” Vanderbilt said, rising slowly. “Because it’s not about trains or steamships anymore. It’s about power, and who gets to hold it. And that’s a question every generation will have to answer for themselves.”

Fulton watched him walk away. “Then let’s hope they remember what we built,” he said quietly, “and also what we failed to see.”

Comments