12. Heroes and Villains of Ancient Greece - Classical Greek Art & Theater

- Historical Conquest Team

- Dec 23, 2025

- 30 min read

My Name is Myron: Sculptor of Motion and Balance

I lived in an age when stone and bronze were learning to move. I was born in the early fifth century BC, in a Greece that had survived invasion and was discovering confidence in its own strength. Artists before me had honored tradition, but I felt the pull of something more demanding. I wanted sculpture to capture life as it is experienced, not as it is remembered. My work became a pursuit of balance, tension, and harmony, shaped by careful observation and restraint.

Learning to See the Living Body

I trained in a world still marked by Archaic forms, where figures stood rigid and timeless. These works were noble, but they did not reflect what I saw in athletes, soldiers, and ordinary citizens. I watched how bodies leaned into effort, how weight shifted instinctively, and how motion was held briefly before release. From this study came my belief that sculpture must capture the moment between actions, where energy is gathered and form is most alive.

The Challenge of Motion

Stone does not move, and bronze only suggests it, yet I made it my task to give both the appearance of life. I chose moments of controlled tension rather than explosive action. A figure at rest reveals little, and one in full release is already past its purpose. The moment before defines everything. Through balance and proportion, I allowed the viewer to feel motion without witnessing it directly. This restraint was essential. Without it, realism becomes chaos.

Craft, Discipline, and Idealization

I did not sculpt individuals as they were, but as they could be at their best. Idealization was not denial of reality, but refinement of it. Athletic forms symbolized discipline, self-mastery, and order. Each limb was measured against the whole, not by numbers alone, but by harmony felt through the eye. Proportion guided my hand, ensuring that strength and grace never competed, but worked together.

Recognition and Influence

My sculptures traveled beyond my workshop, admired and copied by others who recognized the shift taking place. Though many originals were lost to time, their forms endured through replication. Later generations, especially the Romans, preserved my ideas even when my materials disappeared. What mattered was not the surface, but the approach. Sculpture could now suggest life, movement, and intention without abandoning clarity.

What I Leave Behind

I am remembered not for invention alone, but for refinement. I helped sculpture move forward without breaking its discipline. By capturing motion through balance and harmony, I allowed form to speak quietly yet powerfully. My legacy lies in the belief that art reaches its highest purpose not through excess, but through control. In stillness shaped by understanding, sculpture learned to live.

Foundations of Classical Expression: Archaic to Classical Art – Told by Myron

The Classical age, mark the moment when Greek art learned to breathe. I am Myron, a sculptor working in a time when stone and bronze were no longer content to stand stiff and silent. Before my generation, figures faced forward, feet planted evenly, smiles fixed and symbolic. They honored tradition, but they did not yet honor life. What we sought was not rebellion for its own sake, but truth. We wanted the human body to reflect the living tension of muscles, the balance of weight, and the fleeting instant between stillness and motion.

Leaving the Archaic World Behind

In the Archaic age, sculptors followed rules that valued order over observation. The body was reduced to patterns, and movement was implied rather than shown. These forms served religious and cultural needs, but they no longer satisfied a society that had seen war, victory, and loss. After the Persian invasions, Greece understood struggle and motion in a new way. We had watched bodies run, fall, brace, and recover. Art had to catch up with experience. The old symmetry gave way to imbalance, and imbalance gave birth to realism.

Discovering Motion and Balance

My work focused on the moment just before action completes itself. A discus thrower does not exist at rest or release, but in the coiled tension between them. To carve that instant required abandoning rigid frontal poses and embracing contrapposto, the subtle shift of weight that allows one part of the body to relax while another strains. Balance was no longer about symmetry, but about harmony. Each limb had a purpose, each angle a reason. The body became a system rather than a symbol.

Realism Without Excess

We did not chase realism to imitate imperfection. Our goal was idealized truth, not mere copying. Muscles were studied, proportions refined, and movement distilled into its purest form. The human figure became a measure of order, showing how control and freedom could coexist. This balance mirrored what our cities aspired to be: disciplined yet alive, governed yet human.

A New Language of Form

What emerged from this shift was a new artistic language. Sculptures began to invite the viewer to walk around them, to experience form from every angle. The figure existed in space, not against it. Art no longer stood apart from life; it reflected it. This was the foundation of Classical expression, and it shaped everything that followed. By breaking free from rigidity, we allowed stone and bronze to speak of motion, restraint, and harmony. In doing so, we gave Greek art a body that looked not only divine, but unmistakably human.

My Name is Polygnotus of Thasos: Painter of Memory and Meaning

I lived in a time when stories were not only spoken or sung, but painted onto the walls of cities. I was born on the island of Thasos, surrounded by the sea and by legends carried on ships from every corner of the Greek world. From early on, I understood that images had power. A painted figure could teach courage, warn against arrogance, or remind a city of who it believed itself to be. I did not work in silence or for private pleasure. I painted for the public eye, for citizens who gathered before walls as they once gathered before poets.

Learning to Paint Stories, Not Just Figures

In my early years, Greek painting was still bound by convention. Figures were flat, scenes crowded, emotions implied rather than shown. I learned the craft as it existed, but I was never satisfied with mere decoration. I wanted viewers to feel the weight of a moment, to understand a story without needing a guide. I began to experiment with posture, expression, and spacing, arranging figures so that their relationships spoke as clearly as their faces. A bowed head, a turned shoulder, a gaze lifted toward the horizon could reveal grief, hope, or resolve. Painting, I believed, should think as deeply as poetry.

Athens and the Honor of Public Trust

My reputation carried me from Thasos to Athens, where art and civic identity were inseparable. There, I was entrusted with vast public spaces, including the Painted Stoa, where citizens walked, debated, and reflected on their shared past. I painted scenes of heroes, wars, and moral choice, not to glorify violence, but to show its cost and consequence. These works were not owned by a single patron. They belonged to the city itself. That trust mattered deeply to me, and I refused payment for some commissions, believing that art offered to the people should be a gift, not a transaction.

Painting the Inner Life

What set my work apart, others said, was not color or technique alone, but feeling. I sought to paint the inner life of my figures, their hesitation, sorrow, or quiet strength. Even in scenes of myth, I emphasized humanity. Heroes mourned. Victors reflected. The defeated were not faceless. By doing this, I hoped to teach empathy as much as admiration. A city that could see emotion in painted figures, I believed, might better recognize it in one another.

Legacy Beyond the Wall

My paintings have not survived the centuries, but their influence endured long after the plaster crumbled. Later artists spoke of the freedom I introduced, the way narrative and emotion could coexist with order and beauty. I helped move Greek art away from stiffness and toward life, away from symbols alone and toward meaning. Though my hand no longer leaves its mark on stone or wall, the idea that painting can tell stories, shape memory, and guide the soul remains my lasting contribution. I painted not to preserve the past, but to help cities understand themselves in the present, and that, I believe, is why my name is still remembered.

Buildings, Murals, and Shared Visual Narratives – Told by Polygnotus of Thasos

Art as civic identity is not born in private rooms or guarded collections. It lives where citizens walk, argue, remember, and belong. I am Polygnotus of Thasos, and I learned early that painting was not merely a craft, but a public responsibility. In my time, cities did not define themselves only by laws or armies, but by the stories they chose to display. Walls became pages, and murals became lessons, visible to all who passed beneath them. To paint for a city was to help shape how it understood its past, its values, and its future.

The City as the Patron

When I was invited to paint in Athens, I understood that I was no longer working for an individual, but for a people. Public buildings were not empty structures; they were stages for memory. Stoas, temples, and gathering spaces demanded images that could speak without words. My task was not to glorify myself, but to serve the city’s shared identity. The heroes I painted were not distant myths. They were mirrors, reminding citizens of courage, restraint, suffering, and consequence. In choosing what moments to show, we chose what lessons would endure.

Murals as Shared Memory

A mural does not whisper. It stands before everyone, rich and unavoidable. In these vast painted scenes, I arranged figures so that relationships told the story as clearly as action. Victors stood alongside the fallen. The brave shared space with the grieving. By doing this, I hoped viewers would understand that civic greatness was complex, built not only on triumph, but on loss and responsibility. These images became shared reference points. A citizen did not need to be literate to know the story. He needed only to look.

Visual Narratives and Collective Identity

What binds a city together is not uniform thought, but shared understanding. Visual narratives helped create that bond. When Athenians passed painted walls depicting their legendary past or moral struggles, they were reminded that they belonged to something older and larger than themselves. Art reinforced citizenship. It shaped how people spoke about their city, how they judged leaders, and how they understood their role within the whole. A painted figure could quietly teach restraint where speeches failed.

Why Public Art Endures

Paint fades, walls crumble, yet the idea remains. Art placed in public spaces teaches generations not through command, but through presence. It reminds a city who it believes itself to be. That is why art as civic identity mattered so deeply to me. I did not paint to decorate stone, but to give form to shared values. In doing so, I helped cities see themselves reflected on their own walls, and perhaps, to live up to the images they displayed.

My Name is Aeschylus: Playwright of the Gods and the City

I was born into a world where the gods still spoke loudly through myth, ritual, and fear. I did not invent tragedy, but I gave it bones, breath, and purpose. I lived at a turning point in Greek history, when poetry left the fireside and stepped onto the civic stage, when stories became tools for shaping the soul of a city.

Born into a World of Myth and Duty

I was born around 525 BC in Eleusis, a town steeped in sacred mystery. From childhood, I lived close to the rites of Demeter and Persephone, ceremonies that taught us that suffering, death, and rebirth were bound together. These ideas never left me. Even when I stood before thousands in Athens, I wrote as a man shaped by sacred ground, convinced that human fate could not be separated from divine law.

A Soldier Before a Playwright

Before I was known for words, I was known for standing my ground. I fought as a hoplite in the wars against Persia, including the great battles that threatened to erase our way of life. When I later wrote my epitaph, I did not mention my plays at all. I spoke only of Marathon. I believed deeply that citizenship came before art, and that drama existed to serve the city, not the artist.

Finding My Voice on the Athenian Stage

When I began writing for the theater, tragedy was still young and limited. One actor stood opposite the chorus, and stories unfolded slowly. I dared to change that. I introduced a second actor, allowing conflict to live not only between man and fate, but between men themselves. With that change, tragedy became drama, alive with tension, choice, and consequence.

The Chorus as the Soul of the People

I never abandoned the chorus. To me, it was the conscience of the city, the voice of elders, citizens, and sometimes the gods themselves. Through song and movement, the chorus reminded audiences that no act was private, that every decision echoed beyond the individual and into the community.

Justice, Hubris, and the Weight of the Gods

My plays returned again and again to a single truth: arrogance invites ruin. Kings fall not because they are weak, but because they forget their limits. In stories of cursed families and divine judgment, I explored how justice evolves, how vengeance gives way to law, and how societies must learn restraint if they wish to survive.

Writing for the City, Not for Comfort

I did not write to entertain. I wrote to unsettle. The theater was a public space, funded by the city, attended by citizens, and tied to religious festivals. Drama was education, warning, and moral examination. When Athenians watched my plays, they were not escaping reality. They were confronting it.

Success, Rivalry, and Recognition

I won many prizes at the dramatic festivals, yet competition was fierce. Younger playwrights refined the form I helped shape, and some surpassed me in popularity. Still, I knew my role. I had laid the foundation. Others would build higher, but the ground beneath them was firm because I had packed it with purpose.

Exile and Final Years

Late in life, I left Athens and traveled to Sicily, where I continued to write and reflect. There, far from the noise of the festivals, I considered what tragedy had become and what it might endure. My death came quietly, but my stories remained, echoing through generations who still wrestle with justice, power, and the gods.

What I Leave Behind

I am remembered as the father of tragedy, but I see myself differently. I was a bridge between ritual and reason, between myth and law. I showed that stories could shape citizens, that the stage could hold the weight of a civilization’s questions. If my plays still speak, it is because the struggle between pride and humility has never ended.

Why My Voice Still Matters

I believed that societies survive not by ignoring suffering, but by understanding it. Drama, when done rightly, does not flatter the audience. It holds up a mirror and asks whether they recognize themselves. That is the task I set for tragedy, and it is the legacy I leave to all who step onto the stage after me.

Why Gods and Heroes Dominated Art and Drama – Told by Aeschylus

Religion, myth, and artistic purpose are bound together by the belief that human life does not stand alone. I am Aeschylus, and I wrote in an age when the gods were not distant ideas but living forces woven into every decision a city made. Art and drama turned naturally toward gods and heroes because they carried the weight of meaning. Through them, we could explore justice, suffering, pride, and mercy on a scale large enough to instruct an entire people. Mortal lives alone were too small to hold such truths; myth gave us a language vast enough to speak them.

The Gods as Moral Authority

In my world, the gods represented order beyond human law. Zeus embodied justice, Athena wisdom, and the ancient powers beneath them represented forces older than reason itself. When these figures appeared in art and drama, they reminded audiences that human authority was limited. A king could rule a city, but not fate. By placing gods at the center of stories, artists and playwrights showed that actions carried consequences beyond the immediate moment. This was not superstition alone; it was education. A city that understood limits was less likely to tear itself apart through arrogance.

Heroes as the Measure of Humanity

Heroes filled our stories because they stood between gods and men. They were powerful enough to shape events, yet flawed enough to fail. In art and drama, heroes allowed audiences to examine themselves without accusation. When a hero fell to hubris or suffered under a curse, viewers could confront difficult truths at a safe distance. These figures were not models of perfection. They were warnings and questions given form. Through them, we asked what happens when strength outruns wisdom, or when pride silences restraint.

Myth as Collective Memory

Myth endured because it carried shared memory. Long before written history was common, myths preserved lessons about leadership, family, violence, and reconciliation. Artists and dramatists returned to these stories not out of laziness, but because the audience already knew them. That familiarity allowed deeper exploration. When spectators recognized a myth, they were free to focus not on what happened, but on why it mattered. Art and drama thus became places of reflection rather than surprise.

Artistic Purpose Beyond Entertainment

Art was never meant to distract. In tragedy especially, it existed to confront. By invoking gods and heroes, drama elevated private pain into public reflection. A single family’s curse could represent an entire city’s moral struggle. Religious festivals provided the setting because they reminded us that art, like worship, was a communal act. We gathered not to escape suffering, but to understand it together.

Why These Stories Endure

Gods and heroes dominate art and drama because they speak across generations. Human fears and hopes do not change easily. Power still tempts, justice still demands sacrifice, and pride still courts ruin. Myth gives these forces names and faces, allowing each generation to wrestle with them anew. That is why I wrote as I did, and why artists carved and painted what they did. Through gods and heroes, we taught cities how to endure themselves.

Origins of Tragedy: From Choral Hymns to Structured Drama – Told by Aeschylus

The origins of Greek tragedy lie in song, movement, and shared memory long before they took the shape of structured drama. I am Aeschylus, and I inherited a tradition that began not with playwrights, but with worship. In the earliest days, tragedy was born from choral hymns sung in honor of the gods, especially during festivals where the city gathered as one body. These songs did not tell stories as much as they expressed feeling—grief, gratitude, fear, and hope—binding the community through rhythm and voice.

From Ritual to Narrative

At first, the chorus stood alone. It sang of gods, heroes, and ancient deeds, moving in unison as a symbol of collective identity. Over time, these hymns began to focus on specific myths, and narration slowly emerged. A single performer stepped forward to speak in response to the chorus, not as a character at first, but as a storyteller. This simple exchange marked the beginning of drama. The chorus asked, mourned, or warned, and the speaker answered. Meaning began to take shape through contrast.

The Birth of Conflict

True tragedy was born when conflict entered the form. When I introduced a second actor, drama became something new. Dialogue replaced narration, and tension arose between human beings rather than between voice and song alone. Characters could now argue, deceive, plead, and defy one another on stage. The chorus remained, but its role shifted. It no longer carried the story by itself. Instead, it reflected upon the action, offering judgment, fear, or wisdom as events unfolded.

Structure and Purpose

With multiple actors came structure. Stories gained beginnings, crises, and consequences. Scenes followed one another with intention, and themes deepened. Tragedy became a place where justice, fate, and responsibility could be examined through action rather than explanation. The form allowed audiences to witness choices and their costs, rather than merely hear about them. This structure gave tragedy its power. It was no longer ritual alone. It was inquiry.

Why Tragedy Endured

The movement from choral hymn to structured drama transformed worship into reflection. Tragedy kept its sacred roots, but it also became civic education. The audience did not passively listen; they judged, feared, and learned alongside the characters. That is why Greek tragedy endured. It grew from shared song into shared responsibility, using structure to carry ancient truths into a living, questioning form.

Moral Commentary, Rhythm, and Audience Guidance – Told by Aeschylus

The role of the chorus stands at the heart of tragedy, not as decoration, but as conscience. I am Aeschylus, and I never believed the chorus was meant to fade quietly into the background. Before actors spoke as individuals, the chorus was the drama. It carried the memory of ritual, the voice of the people, and the presence of the divine. Even as tragedy grew more complex, I kept the chorus central, because it bound the audience to the action unfolding before them.

The Voice of the Community

The chorus speaks not as a single person, but as many. It represents elders, citizens, or witnesses who stand close to the events but do not control them. Through the chorus, the audience hears its own doubts, fears, and hopes echoed back from the stage. When the chorus reacts with horror, restraint, or sympathy, it guides the audience toward reflection without command. This shared voice reminds spectators that private choices carry public weight.

Moral Commentary Without Judgment

The chorus does not issue verdicts. Instead, it asks questions, recalls old laws, and warns of consequences. Its songs connect present actions to past stories, linking each tragedy to a larger moral order. By doing this, the chorus teaches without preaching. It leaves room for the audience to wrestle with meaning, to feel unease, and to recognize complexity. Tragedy would lose its depth if answers came too easily.

Rhythm as Emotional Structure

Song and movement shape how tragedy is felt as much as what is said. The chorus sets the rhythm of the play, giving the audience time to breathe, grieve, and reflect. Between moments of intense dialogue, choral odes slow the pace, allowing emotion to settle and understanding to grow. Rhythm transforms raw action into experience, ensuring that tragedy reaches the heart as well as the mind.

Guiding the Audience Through Suffering

Tragedy asks much of its audience. Without guidance, suffering can overwhelm or confuse. The chorus provides a path through darkness, acknowledging fear while pointing toward wisdom. It reminds spectators that pain has meaning and that endurance is possible. In this way, the chorus stands as both guide and companion, ensuring that tragedy fulfills its purpose not by shocking alone, but by leading the audience toward insight.

Festivals, Citizenship, and Collective Experience – Told by Aeschylus

Theater and the city-state were never separate worlds. I am Aeschylus, and in my lifetime drama belonged to the people as fully as law courts and assemblies. Tragedy was not performed in quiet halls for private reflection, but in open spaces during sacred festivals, when the city paused its labor and gathered as one. These occasions reminded us that art was a public act, rooted in worship and sustained by citizenship. To attend the theater was to take part in the life of the polis.

Festivals as Sacred Civic Time

Our greatest plays were staged during religious festivals, especially those honoring Dionysus, where sacrifice, procession, and performance formed a single rhythm. These festivals were not escapes from civic duty; they were expressions of it. The city funded the performances, appointed officials to oversee them, and invited citizens to judge them. By placing drama within sacred time, we acknowledged that reflection on justice, suffering, and fate was itself a form of worship. The gods were present not only in the stories, but in the act of gathering to hear them.

Citizenship on the Stage and in the Seats

The audience was not a passive crowd. It was the city itself, composed of citizens who debated laws, served in war, and shared responsibility for Athens’ future. What they witnessed on stage reflected their own choices and fears. Kings who overreached, families torn by vengeance, and communities struggling to replace bloodshed with law were not distant tales. They were mirrors. Theater allowed citizens to examine the moral consequences of power and pride together, without accusation, but not without challenge.

A Collective Experience of Learning

Tragedy demanded collective attention. Thousands watched the same story unfold, felt the same tension, and shared the same silence after disaster struck on stage. This shared experience created a common emotional language. It taught citizens how to feel together, how to grieve together, and how to think about justice beyond personal interest. The chorus strengthened this bond, speaking as a communal voice that guided reflection rather than dictating belief.

Why Theater Mattered to the Polis

Theater mattered because it trained the soul of the city. Laws could command behavior, but drama shaped judgment. By placing the city-state inside stories of gods and heroes, tragedy invited citizens to consider what kind of community they wished to be. In this way, theater became a form of civic education, as essential as debate or service. When the festival ended and daily life resumed, the questions raised on stage remained, carried by citizens back into the life of the polis itself.

Facial Expression, Posture, and Storytelling Through Images – Told by Polygnotus

Painting emotion and narrative requires more than skill with color or line; it demands understanding the inner life of the figure. I am Polygnotus of Thasos, and I believed that a painted image should speak even in silence. Before my time, figures often stood stiff and uniform, their faces calm regardless of circumstance. Such images told us who a person was, but not what they felt. I sought to change that. To tell a story through painting, emotion had to be visible, and meaning had to flow from the relationship between bodies, gestures, and space.

The Face as a Window to Meaning

Facial expression became one of my most important tools. A lowered gaze could speak of grief, a tightened mouth of resolve, a distant stare of foreknowledge. I did not exaggerate these features, but refined them, allowing subtle changes to suggest deep feeling. In this way, a viewer could recognize sorrow, fear, or calm without instruction. Emotion guided understanding. When citizens looked upon such faces, they were not simply observing myth; they were encountering familiar human experience shaped by story.

Posture and the Language of the Body

The body often tells what the face conceals. I arranged figures so that posture revealed intention and consequence. A hero leaning forward suggested urgency, while one turned away suggested doubt or loss. Groups were positioned to show connection or isolation, unity or division. By carefully placing limbs and adjusting the angle of the torso, I allowed movement and stillness to become part of the narrative. These choices guided the viewer’s eye, leading it through the scene as one might follow lines of poetry.

Narrative Without Words

A mural must tell its story without sound. There is no chorus, no actor’s voice, only image. This challenge forced clarity. Each figure had to belong to the moment, and each moment to the whole. I used space to suggest time, allowing viewers to sense what had happened before and what might follow. In doing so, painting became not a single image, but a sequence of thought. The viewer completed the story through recognition and reflection.

Why Emotion Matters in Art

Emotion gives art its power to teach. When citizens recognized themselves in painted grief or resolve, the story remained with them long after they passed the wall. Painting emotion and narrative transformed images from symbols into experiences. It allowed art to shape memory and understanding quietly, persistently, and across generations. That was my aim: to let images speak the language of humanity, even when words fell silent.

Early Depth, Background Scenes, and Symbolic Placement – Told by Polygnotus

Myth in color and space is where painting learned to think beyond the surface. I am Polygnotus of Thasos, and I worked in a moment when images began to move outward instead of pressing flat against the wall. Earlier painters placed figures side by side, crowded into a single plane, each competing for attention. I wanted space to speak as clearly as color. Myth demanded more than figures alone; it required setting, distance, and placement that reflected meaning as much as action.

Creating Depth Without Illusion

In my time, we did not yet possess the rules of perspective that later artists would master, but we understood that space could suggest depth through arrangement. I placed figures at varying heights, allowing some to stand above others, some to recede, and some to emerge forward. This created a sense of environment rather than decoration. Mountains, walls, and pathways were not painted to fool the eye, but to guide it. The viewer understood where events unfolded, not because space was measured, but because it was meaningful.

Background as Story, Not Ornament

Background scenes were never empty. They carried memory and consequence. A figure placed near a wall, a cliff, or an opening was shaped by that setting. These elements suggested what had happened before and what might follow. In myths of war or judgment, the background might echo loss or inevitability. In scenes of heroism, it could suggest distance traveled or fate awaiting fulfillment. Space became part of the narrative, silently reinforcing the story told by the figures themselves.

Symbolic Placement of Figures

Where a figure stood mattered as much as who that figure was. Central placement suggested authority or moral focus. Figures pushed to the edge implied exclusion, defeat, or transition. I used spacing to show relationships between gods, heroes, and mortals, allowing proximity or separation to reflect harmony or tension. Through placement alone, viewers could sense alliances, conflicts, and hierarchies without a single word being spoken.

Color as Emotional Geography

Color guided emotion across space. Brighter tones drew attention to moments of importance, while subdued hues softened areas meant for reflection rather than action. Color helped distinguish divine from mortal, present from past, hope from mourning. When paired with careful placement, color turned walls into landscapes of meaning rather than mere surfaces to be filled.

Why Space Changed Myth

By giving myth depth and space, painting moved closer to lived experience. Stories no longer floated outside the viewer; they unfolded within a world that felt navigable and human. This allowed citizens to enter the myth mentally, to walk through it with their eyes and carry its lessons with them. Myth in color and space transformed painting into a form of silent storytelling, capable of shaping memory and understanding long after voices faded from the square.

Motion in Sculpture: Balance, Tension, and Frozen Movement – Told by Myron

This is an attempt to hold time still without killing it. I am Myron, and my work was shaped by the desire to show the body not at rest, but in the moment where effort, balance, and intention converge. Earlier sculptors favored stillness because stone and bronze seemed to demand it. Yet the human body is rarely still. It leans, twists, braces, and releases. To ignore this was to ignore truth. My challenge was to honor movement while preserving harmony.

The Moment Between Action and Release

True motion in sculpture does not lie in the act itself, but in the instant just before completion. This is where tension gathers and balance is most fragile. I studied athletes closely, watching how weight shifted and muscles responded in anticipation. By choosing this moment, I allowed the viewer to sense what came before and what must follow. The body appears alive because it is caught in decision, not conclusion.

Balance as Controlled Instability

Balance in motion is never symmetrical. One leg bears weight while another prepares to move. The torso twists to counter the pull of arms and shoulders. This controlled instability is what gives a figure energy. In my sculptures, every angle serves another, ensuring that no movement feels accidental. The figure stands because it must, not because it is frozen. Balance becomes the quiet structure that allows tension to speak.

Tension Made Visible

Muscles under strain reveal purpose. They show effort, concentration, and resolve. I shaped tension carefully, avoiding excess that would distort form or distract from unity. The goal was not raw power, but clarity. When tension is properly placed, the body communicates intent without gesture or expression. The viewer understands action through form alone.

Frozen Movement as Enduring Life

A sculpture cannot move, but it can suggest motion endlessly. Frozen movement allows a single moment to repeat itself in the mind of the viewer. Each glance reactivates the tension and balance held within the form. This is why capturing motion mattered. It allowed sculpture to step beyond symbol and become experience. Through balance, tension, and carefully chosen stillness, stone and bronze learned to speak the language of life.

Idealized Human Form: Athleticism, Proportion, and Harmony – Told by Myron

The idealized human form stands at the meeting place of observation and aspiration. I am Myron, and when I shaped athletes in bronze, I was not attempting to copy a single body, but to reveal what the human form could represent at its best. In my time, the athlete was more than a competitor. He was a symbol of discipline, balance, and self-mastery. Sculpture sought to honor these qualities by shaping bodies that expressed strength without excess and grace without weakness.

Athleticism as Moral Expression

Athletic bodies mattered because they reflected character as much as muscle. Training demanded restraint, endurance, and respect for limits. In sculpting athletes, I aimed to show effort held in check, power guided by control. The body became a visible record of discipline. This is why exaggeration had no place. Excessive bulk or dramatic distortion would betray the harmony that true athleticism required.

Proportion and the Search for Order

Proportion gave form its logic. Each limb had to relate meaningfully to the whole, not through rigid measurement, but through visual balance. I studied how length, width, and mass interacted, ensuring that no element dominated at the expense of unity. Proportion was not mathematics alone. It was judgment refined through experience. A well-proportioned figure feels inevitable, as though it could exist no other way.

Harmony Between Stillness and Movement

Even when figures stood still, they carried the memory of motion. Harmony emerged from the relationship between relaxed and engaged muscles, between stability and readiness. This balance reflected the ideals of the society that produced it, one that valued order without stagnation and freedom without chaos. The idealized human form embodied this tension, showing how strength and beauty could coexist without conflict.

Why Idealization Endured

Idealization was not denial of reality, but refinement of it. By shaping the human form toward harmony, sculpture offered a model of balance that extended beyond the body. It suggested how individuals might align effort with restraint and ambition with order. That is why the idealized human form endured. It spoke not only of bodies in motion, but of ideals that shaped the life of the city itself.

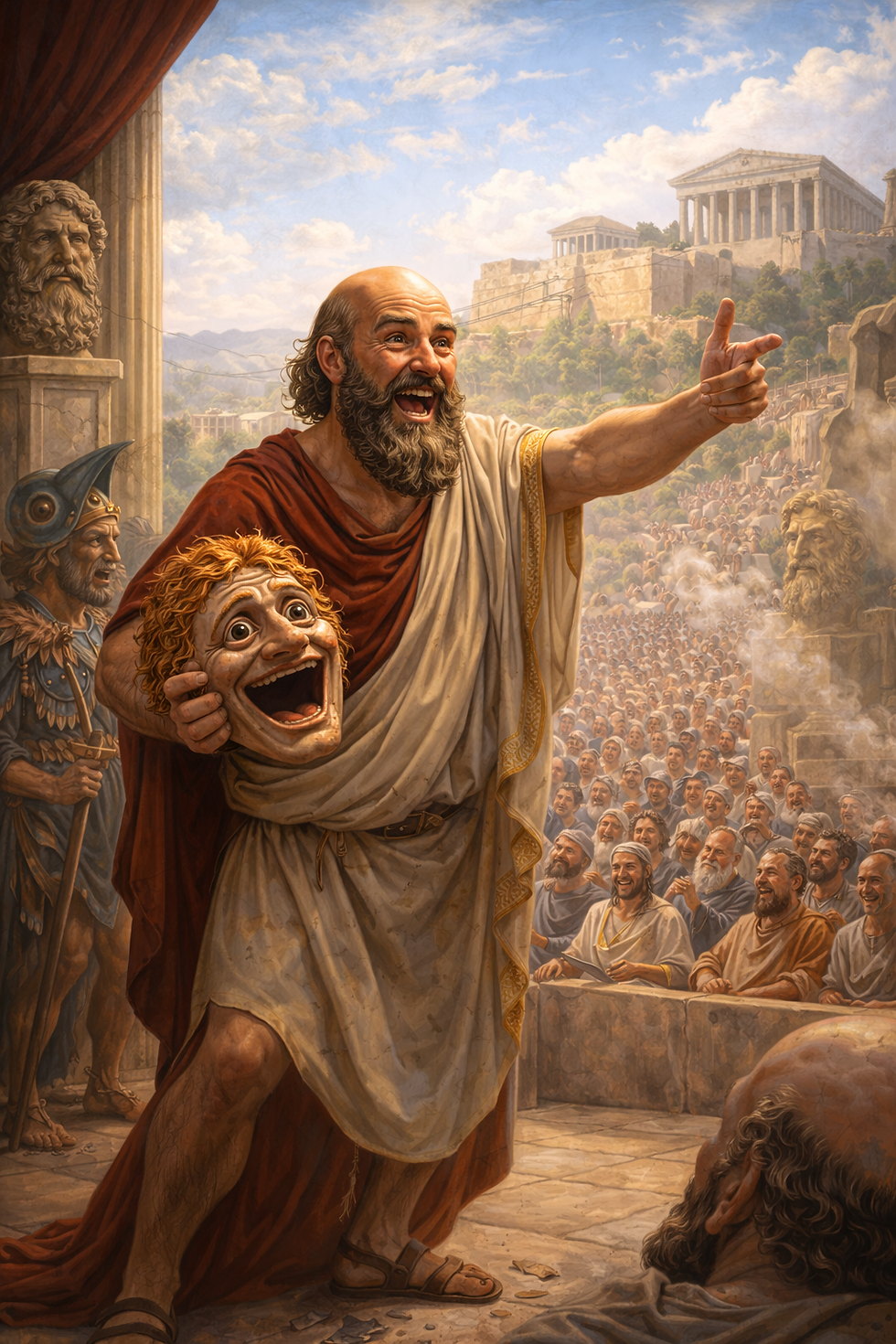

My Name is Aristophanes: Playwright of Laughter and Reckoning

I was born into a city that believed words could move crowds as surely as armies. Athens in my lifetime was loud, confident, wounded, and endlessly talkative. I learned early that laughter was not the opposite of seriousness, but one of its sharpest forms. Comedy, when wielded boldly, could expose vanity, challenge power, and force a city to hear truths it would otherwise refuse.

Growing Up in a City at War with Itself

I came of age during the long and exhausting Peloponnesian War, when Athens spoke proudly of wisdom while bleeding its own future. Politics filled every street and household, and public debate was constant. I watched leaders rise on clever speeches and fall just as quickly. These experiences shaped my voice. I did not write from the safety of abstraction. I wrote from the noise of assemblies, the rumors of the marketplace, and the fear that democracy could destroy itself through arrogance and excess.

Choosing Comedy as a Weapon

When I began writing for the theater, tragedy already commanded respect, but comedy held a different kind of power. I embraced exaggeration, fantasy, and insult not to escape reality, but to reveal it. On stage, I could give form to absurd ideas and let the audience judge them openly. I named names. I mocked generals, philosophers, politicians, and even the city itself. Comedy allowed me to speak plainly while hiding behind laughter, a disguise that made dangerous truths easier to hear.

The Stage as Public Trial

My plays were not polite entertainment. They were confrontations. Masks, choruses, and outrageous plots gave me freedom to say what could not be spoken in the assembly. I imagined worlds where women seized power to end war, where birds founded their own city, and where old ideas were put on trial. These were not fantasies for their own sake. They were mirrors held up to Athens, asking whether wisdom had been replaced by noise, and whether cleverness had become more important than virtue.

Conflict, Criticism, and Persistence

Not everyone welcomed my voice. I was criticized, attacked, and accused of undermining the city in its time of need. Yet I persisted, because I believed loyalty did not mean silence. A city that could not laugh at itself, I thought, was already in danger. Over time, my work shifted in tone, becoming less savage and more reflective, but my purpose remained the same: to challenge complacency and force reflection through humor.

What Remains After the Laughter

As I grew older, I watched Athens change, humbled by defeat and exhaustion. The laughter I once provoked had a different sound in those years, quieter and edged with memory. Still, I believed comedy mattered. Long after laws were repealed and speeches forgotten, a joke could survive, carrying with it a warning or a lesson. That is the legacy I leave behind. I proved that comedy could think, that laughter could teach, and that the stage could hold a city accountable without lifting a sword.

Rise of Comedy: How Comedy Emerged Alongside Tragedy – Told by Aristophanes

The rise of Greek comedy did not come in opposition to tragedy, but in conversation with it. I am Aristophanes, and I wrote in a city where citizens spent their days listening to speeches, weighing laws, and judging leaders. Tragedy taught us how power failed and fate punished pride. Comedy asked what happened when those same lessons were ignored in everyday life. As tragedy took the grand myths of gods and heroes, comedy turned its gaze toward the living city, revealing its habits, contradictions, and excesses through laughter.

Shared Origins in Festival and Ritual

Comedy, like tragedy, was born in the festivals honoring Dionysus. Both forms emerged from processions, song, and communal celebration. Early comic performances relied on exaggeration, obscenity, and parody, but beneath the noise lay ritual purpose. Laughter released tension just as tragedy confronted it. Together, they formed a balance, allowing the city to experience fear, pity, and relief within the same sacred space. Comedy did not diminish tragedy. It completed it.

A Different Kind of Truth

Where tragedy used myth to explore universal laws, comedy used the present moment. We placed recognizable figures on stage, sometimes disguised, sometimes named outright. Comedy thrived on immediacy. It responded to speeches given the week before, policies debated in the assembly, and fears whispered in the streets. This closeness gave comedy its sharp edge. It spoke truths that tragedy, bound to ancient stories, could not reach directly.

Fantasy as Critique

Comedy embraced the impossible to expose the absurd. Flying cities, talking birds, and worlds turned upside down allowed audiences to laugh first and reflect afterward. By exaggerating reality, comedy revealed its flaws more clearly. Tragedy warned of what happens when fate is defied. Comedy asked why we keep defying reason even after the warning is known.

Why Comedy Endured Beside Tragedy

Comedy endured because cities need more than solemn instruction. They need self-awareness. By standing beside tragedy, comedy ensured that reflection did not harden into despair. Together, the two forms created a complete dramatic language. One taught through suffering, the other through laughter, and both reminded the city that understanding itself was the first step toward survival.

Satire, Politics, and War: Mocking Leaders and Policies – Told by Aristophanes

Satire, politics, and war were inseparable in my lifetime, because Athens never stopped talking about itself. I am Aristophanes, and I lived in a city that debated war in the morning, suffered it by night, and argued again the next day as if words alone could shield us from consequence. Comedy gave me the freedom to confront this contradiction openly. Where speeches promised glory and necessity, satire exposed vanity, fear, and foolish persistence. Laughter became a way to say what anger could not sustain.

Mocking Power to Reveal Truth

I mocked leaders not because I despised authority, but because unchecked power invites disaster. Generals, politicians, and popular speakers all appeared on my stage, sometimes thinly disguised, sometimes unmistakable. By exaggerating their traits, I revealed their blind spots. A leader obsessed with honor became ridiculous when stripped of ceremony. A policy defended with endless words collapsed when reduced to its simplest logic. Satire allowed the audience to see through confidence and rhetoric to consequence.

War as Absurd Repetition

War dominated our lives for decades, and its language became empty through repetition. Promises of victory sounded the same each year, while losses accumulated quietly. Comedy interrupted this cycle. By presenting war as absurd rather than heroic, satire forced citizens to confront its cost without the armor of pride. Laughter created distance, allowing reflection where fear had failed. When the audience laughed, they also recognized themselves.

Public Behavior Under the Lens

Comedy did not spare the people themselves. Citizens who cheered foolish proposals, rewarded empty speeches, or followed fashion instead of reason found their reflections on stage. Satire reminded the audience that democracy required judgment, not noise. By mocking public behavior, I insisted that responsibility did not belong to leaders alone. The city shaped its fate collectively, and laughter revealed how easily that duty was forgotten.

Why Satire Mattered in Wartime

In times of war, truth is easily buried beneath necessity. Satire dug it back up. By laughing at leaders, policies, and ourselves, we loosened fear’s grip long enough to think. Comedy did not end wars, but it challenged the habits that sustained them. That is why satire mattered. It gave the city a mirror when it most needed one, even when the reflection was uncomfortable.

Theater as Free Speech: What Could Be Said on Stage – Told by Aristophanes

Theater as free speech was one of the boldest experiments my city ever attempted. I am Aristophanes, and I wrote in a democracy that believed words were power, yet feared where those words might lead. On the comic stage, I was granted freedoms that did not exist elsewhere. I could mock leaders, question policies, and expose foolishness before thousands, all under the protection of festival tradition. The theater became a space where speech was loosened, not to destroy the city, but to test it.

What the Stage Allowed

Comedy permitted directness that the assembly often avoided. On stage, I could exaggerate real figures, twist their arguments into absurd shapes, and lay bare the contradictions hidden beneath polished speeches. The mask protected both speaker and audience. Because words were spoken by characters, not citizens, truths could be aired without immediate consequence. This freedom depended on ritual and timing. The festival created a temporary suspension of restraint, a shared agreement that laughter could say what formal debate could not.

The Boundaries of Freedom

Yet freedom was not without limits. The stage allowed insult, but not chaos. It allowed mockery, but not open calls for rebellion. Comedy could challenge authority, but it could not dismantle the city itself. There were lines shaped by custom, religion, and public tolerance. A joke that struck too deeply risked backlash, and I faced criticism and accusation more than once. Free speech on stage survived only as long as it was understood to serve reflection rather than destruction.

Why Comedy Could Speak Freely

Comedy succeeded as free speech because it framed criticism as play. Laughter softened resistance, allowing ideas to enter where anger would be barred. The audience could enjoy the joke while absorbing the warning beneath it. This balance mattered. Without humor, criticism hardened into threat. Without critique, laughter became empty noise. The comic stage walked between these extremes, offering truth disguised as entertainment.

The Legacy of the Open Stage

Theater as free speech did not promise agreement. It promised exposure. By allowing difficult ideas to surface publicly, the stage trained citizens to hear dissent without panic. It reminded the city that silence was more dangerous than laughter. Though the freedoms of comedy were imperfect and temporary, they showed what a society could risk in the name of self-understanding. That is why the theater mattered. It was not merely a place of amusement, but a testing ground for the courage to listen.

Western Culture: How Greek Art and Drama Shaped Roman, Renaissance, and Modern Traditions – Told by Aristophanes, Myron, Polygnotus, and Aeschylus

Lasting influence on Western culture is not the result of imitation alone, but of inheritance shaped and reshaped across centuries. We speak together now, voices from different crafts united by a shared legacy. Though our works were rooted in the city-states of Greece, they did not remain there. Rome, the Renaissance, and the modern world carried our ideas forward, adapting them to new powers, new faiths, and new questions, yet always returning to the foundations we laid.

From Greece to Rome: Structure, Order, and Civic Purpose

When Rome rose, it did not invent its culture from nothing. It absorbed ours. Roman sculptors studied the balance and idealized form shaped by hands like mine, preserving Greek bodies in marble long after bronze originals were lost. Roman painters and architects inherited the idea that public art should instruct as well as impress, turning forums, baths, and monuments into civic classrooms. Roman drama borrowed our structures, our masks, and our chorus, reshaping them for Latin voices and imperial audiences. Even when power shifted, the belief that art and theater belonged to public life endured.

Reawakening in the Renaissance

Centuries later, Europe looked backward to move forward. Renaissance artists rediscovered the human form as a measure of beauty, harmony, and meaning, echoing the balance and proportion once carved and painted in Greece. Painters explored depth, emotion, and narrative in ways that reflected lessons first learned on Greek walls. Playwrights returned to structured drama, conflict, and character shaped by moral consequence. Tragedy and comedy regained their seriousness, not as entertainment alone, but as tools for examining power, ambition, and human failure.

Modern Art and Theater: Old Questions in New Forms

In the modern world, our influence appears less in imitation and more in approach. Sculptors still chase motion held in stillness. Painters still use space, placement, and expression to guide meaning. Theater still wrestles with justice, identity, and authority, whether on grand stages or intimate ones. Comedy still mocks power, tragedy still confronts suffering, and both rely on audiences willing to reflect together. The forms evolve, but the purpose remains recognizable.

Why Our Legacy Endures

What we passed on was not style alone, but belief. We believed art should engage the mind and the community, that drama should ask difficult questions, and that beauty and meaning were inseparable. Western culture returned to these ideas again and again because they proved resilient. They adapted to empires, religions, revolutions, and technologies without losing their core. That endurance is our true legacy. We shaped not only how art looks or how stories are told, but why societies continue to tell them at all.

Comments