4. Heroes and Villains of the Industrial Revolution - Expansion & Globalization (1750-1790) in the Industrial Revolution

- Historical Conquest Team

- Jul 7, 2025

- 43 min read

My Name is Adam Smith (1723–1790): A Life Shaped by Inquiry

I was born in the small Scottish town of Kirkcaldy in 1723. My father, a customs officer, had died before I was born, so I was raised by my devoted mother, Margaret Douglas. She nurtured in me a quiet but persistent curiosity, and from an early age, I found myself fascinated by books, ideas, and the rhythm of thought. It was said I was once kidnapped by gypsies as a toddler, but thankfully I was quickly returned. That episode aside, my youth was calm, filled with reading, reflection, and early schooling that fed my desire to understand the world around me.

A Scholar Among Giants

At fourteen, I entered the University of Glasgow. There I studied moral philosophy under Francis Hutcheson, a powerful influence on my thought. Hutcheson spoke of natural rights, human benevolence, and the invisible principles that guided society—concepts that stirred something deep in me. After Glasgow, I earned a scholarship to Oxford, where I found the education less stimulating than I had hoped. Oxford taught Latin and Greek, but it had grown complacent. Still, I continued studying on my own, developing a passion for ancient texts, modern philosophy, and the structures of society.

Lecturer and Philosopher in Edinburgh

Returning to Scotland, I began delivering public lectures in Edinburgh. These lectures explored rhetoric, jurisprudence, and political economy—laying the groundwork for ideas I would later refine. I earned a professorship at the University of Glasgow in 1751. There I taught logic, and soon after, moral philosophy. I loved teaching. The students were sharp, the city intellectually vibrant, and my ideas began to take shape in ways I hadn’t foreseen.

It was during these years I wrote The Theory of Moral Sentiments, published in 1759. I argued that human beings are not driven only by self-interest but also by sympathy—our ability to place ourselves in the situation of another. This “impartial spectator,” as I called it, helps us develop moral judgment. It was a deeply personal book, one that many readers remember me by, even though my later work would overshadow it.

The Grand Tour and New Observations

In 1763, I left Glasgow to serve as a tutor to the young Duke of Buccleuch. This journey took us through France, where I met Voltaire, Diderot, and the physiocrats—early economists who emphasized land and agriculture as sources of wealth. These conversations challenged my thinking. I began to see that the true source of a nation’s prosperity lay not in gold or grain alone, but in the productive labor of its people.

It was during this time that the idea for my second and most famous book began to take shape. I returned to Kirkcaldy in 1766 and spent nearly a decade in deep study and writing. The manuscript grew steadily, as I attempted to map out the principles that governed trade, labor, and economic growth.

The Wealth of Nations

In 1776, the same year America declared independence, I published An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. It was a thick book, layered with argument, observation, and analysis. I argued that free markets, driven by individual self-interest, tended to produce the most efficient and fair outcomes—almost as if guided by an “invisible hand.” I spoke of the division of labor, which increased productivity, and the dangers of monopolies and mercantilism, which distorted natural economic flow.

The book was well received. Though dense, it offered clarity on the forces shaping modern economies. It spoke not just to kings and merchants but to the changing world—one increasingly driven by trade, factories, and global expansion. It helped shape a new field: political economy.

A Quiet End with Lasting Echoes

I was appointed commissioner of customs in Edinburgh in my later years. The position was ironic, considering my critiques of government interference, but it suited me. I lived modestly, never married, and spent my days in study and walks with friends. I died in 1790, quietly, in the city I loved.

Though my bones lie buried in Canongate Churchyard, my ideas did not fade. They echoed through the industrial age, shaping capitalism, modern economics, and the policy debates of nations long after I had gone. I never thought of myself as a revolutionary—but perhaps, in my own way, I was.

If I taught the world anything, it is that human society, though complex, follows patterns that we can understand—and that through understanding, we might improve the condition of all.

The Enlightenment Spirit and the World It Touched – Told by Adam Smith

The century in which I lived and worked was one lit by the lamp of reason. We called it the Enlightenment—a time when philosophers, scientists, and thinkers across Europe began to question long-standing traditions, challenge old authorities, and search for knowledge through observation, logic, and experiment. It was not one movement, but many minds coming alive at once. From Edinburgh to Paris, from Königsberg to Philadelphia, the air buzzed with ideas about liberty, reason, science, morality, and human potential. I was honored to be part of this transformation, as were my friends and peers—David Hume, Voltaire, Rousseau, and others. We sought not only to understand the world but to improve it.

Ideas in the Coffeehouses and Courts

The Enlightenment was not confined to universities or royal salons. Ideas found fertile ground in coffeehouses and printing shops, where pamphlets and books traveled faster than armies. These ideas spoke of natural rights, constitutional government, education, and justice. In France, Montesquieu explored the separation of powers. In America, men like Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin translated Enlightenment ideals into revolutionary documents. I myself sought to understand the forces of economics not as a mysterious gift of kings but as a system of natural laws, driven by labor, trade, and human action.

The strength of this movement lay in its universality. It did not matter whether one was Scottish or Prussian, Catholic or Protestant. Reason was a common language. And through it, humanity began to imagine a world ruled not by superstition or tyranny, but by knowledge and fairness.

Liberty and the Market Mind

In my own writings, particularly The Wealth of Nations, I built upon Enlightenment reasoning to explain the principles that governed commerce and society. I argued that when individuals pursue their own interests within a framework of justice, they unintentionally promote the good of society—a phenomenon I called the invisible hand. This was not a call for greed, but for freedom. Markets worked best when they were allowed to function naturally, without excessive interference from kings or monopolies.

This idea of natural liberty resonated far beyond economics. It was part of a larger current of thought—one that believed individuals were capable of managing their own lives, forming rational governments, and improving the human condition through education and exchange. It was this same current that inspired revolutions, reformed laws, and challenged the divine right of monarchs.

Revolutions of Thought and Power

From the American colonies to the salons of Paris, Enlightenment thought became action. In 1776, the same year my great treatise was published, American colonists declared their independence, invoking the principles of liberty and equality. They argued not for a mere change of rulers, but for a new kind of society based on Enlightenment ideals. Across the Atlantic, the French Revolution soon followed, with cries of liberty, fraternity, and equality echoing in the streets.

But Enlightenment influence reached even further. In Haiti, enslaved people began to question the very foundations of colonial oppression. In South America, revolution stirred in the hearts of young criollos who had read the same texts and believed in the same rights. Even in India and China, European merchants and scholars carried with them not only goods but books, philosophies, and debates. Enlightenment ideals became global—sometimes welcomed, sometimes resisted, always disruptive.

Industry and the Mind’s Inventions

While revolutions reshaped nations, another force was reshaping how people lived and worked. The Industrial Revolution—whose early stages I witnessed—was a child of Enlightenment thinking. It was not born of brute force, but of invention. Men like James Watt took scientific principles and applied them to engines. New machines increased productivity, trade routes expanded, and markets grew. The same spirit of inquiry that drove philosophers now powered workshops.

This transformation was not without consequence. Cities swelled, labor changed, and old ways of life were swept aside. Enlightenment thinkers, myself included, did not fully anticipate the social strains that would follow. But we believed in progress—that knowledge could lead to better conditions for all, if governed with care and conscience.

A Legacy to Be Continued

As I near the end of my story, I see a world in motion—nations rethinking their laws, economies shifting under new forces, and minds questioning the unquestioned. This is the legacy of the Enlightenment. We believed that human beings were not creatures of fate, but agents of change. We trusted that truth could be discovered, and that society could be improved by rational thought and fair institutions.

Though I have passed from the world of markets and monarchs, I hope the ideas we shared continue to guide it. May liberty remain sacred, reason remain trusted, and every man and woman be free to think, to speak, and to labor in dignity.

The Rise of Capitalism and the Global Market Economy – Told by Adam Smith

During my lifetime, I watched the world change in ways no generation before had witnessed. Fields gave way to factories. Merchants sailed farther and traded faster. Goods once rare became common, and wealth no longer rested solely in land or noble title but in enterprise and ingenuity. This was the rise of capitalism—not just a system of wealth-making, but a revolution in how societies worked, how people lived, and how nations grew. It was not born overnight. It rose from centuries of trade, discovery, and labor. But between 1750 and 1790, its form began to solidify. This was the age when the wheels of the market began to spin without ceasing, driven by self-interest, competition, and the pursuit of profit.

The Invisible Hand of Human Motives

In my own study of economics, I observed that individuals, in seeking to improve their own condition, often ended up improving society as a whole—even if that was not their intention. I called this phenomenon the “invisible hand.” A baker does not make bread out of kindness alone, but to earn a living. Yet by doing so, he feeds a community. A merchant trades not for charity, but for gain. Yet the exchange of goods fuels towns, ports, and entire nations. This idea formed the foundation of capitalism: that decentralized decisions, guided by prices, competition, and innovation, could produce order, growth, and prosperity better than centralized commands ever could.

Breaking from Mercantilist Chains

Before this new era, most governments followed mercantilist policies. They believed wealth was finite, hoarded like gold, and that one nation could only gain by taking from another. Trade was tightly controlled. Colonies were used to enrich the mother country, and monopolies ruled the marketplace. But I argued in The Wealth of Nations that wealth is not a fixed quantity. It grows when people specialize in what they do best and trade freely. Labor, not gold, is the true source of a nation’s wealth. When individuals are free to pursue enterprise under laws that protect property and contracts, the economy expands for all.

The Division of Labor and New Productivity

One of the most striking engines of this new capitalism was the division of labor. I often used the example of a pin factory: one man could scarcely make a pin in a day, but ten men, each performing one simple step, could produce thousands. This specialization increased productivity beyond anything previously imagined. It also changed how work was understood—no longer a single craft, but a chain of connected tasks. This principle, applied broadly, reshaped agriculture, manufacturing, and even education. It laid the groundwork for the factories that soon emerged across Britain and beyond.

A World in Exchange

Capitalism did not remain confined to Britain. Trade routes stretched across the seas, linking Europe, Africa, the Americas, and Asia. Raw materials like cotton, sugar, and tobacco flowed in. Manufactured goods and weapons flowed out. Tea from China, spices from India, and silver from the Americas all moved through global networks that connected farmers and artisans to distant markets they would never see. This was the global market economy taking shape. It created opportunity and innovation, but also inequality, exploitation, and dependency—especially for those who labored under empire or in bondage.

Capital and Credit Expand the Frontier

As enterprise grew, so did the need for capital—money to invest in ships, shops, mills, and machines. Banks expanded, credit markets deepened, and financial instruments became tools of risk and reward. The accumulation and investment of capital became the heartbeat of modern economies. It allowed new ventures to rise quickly, but it also tied workers and investors alike to the rhythms of commerce. Profit became not just a reward, but a signal—guiding labor, prices, and production across continents.

Freedom, Inequality, and the Moral Challenge

While I championed the liberty of markets, I did not turn a blind eye to their consequences. I feared that unchecked greed could lead to monopoly, corruption, or exploitation. I argued that government had a duty to provide public goods, enforce justice, and ensure fair competition. Capitalism, to function well, must rest on a foundation of moral sentiment and legal order. Without it, markets can lose their way. The global economy of my day brought prosperity to many, but it was also built on the back of enslaved labor, colonial extraction, and political domination. These contradictions haunted the system’s promise.

A System Still Taking Shape

By the end of my life, the world was firmly on the path to becoming a capitalist one. Industry, trade, and finance were no longer local matters—they were international forces. The wealth of nations was no longer counted in kings' vaults, but in fields of cotton, rows of looms, and bustling ports filled with cargo. The rise of capitalism had begun a transformation that would touch every corner of the globe and every aspect of human life.

I leave behind my thoughts not as doctrine, but as observations to be refined by the generations to come. Capitalism is neither perfect nor permanent. It is a tool—a powerful one—that, when guided by justice, reason, and virtue, can improve the lives of many. But it must be watched, questioned, and shaped by the very people it serves. For in the end, the wealth of nations is not measured in coins, but in the flourishing of human lives.

My Name is Catherine the Great (1729–1796): The Making of an Empress

I was born Sophia Augusta Frederica in Stettin, in the Kingdom of Prussia, in 1729. My family was noble, though not especially powerful. My father was a minor prince, and my mother had dreams that extended far beyond our modest court. From an early age, I was raised with the expectation that I would marry well, learn quickly, and play a role on a larger stage. I read voraciously, studied philosophy, history, languages, and diplomacy, and watched my mother maneuver us closer to power. Opportunity came when the Empress of Russia, Elizabeth, sought a bride for her nephew and heir, Peter.

At just fourteen years old, I left my home and traveled to the Russian court. I converted to the Russian Orthodox faith and took the name Catherine. It was a bold step, not just of religion but of identity. I embraced Russia as my own, even though I was a foreigner in a land of cold winters and intricate politics. I married Peter, but it was not a marriage of love or even of alliance. It was a stepping stone, and I quickly realized that I would need to rely on my own strength to survive in this world.

The Road to Power

My husband, Peter III, was unstable, unpopular, and more loyal to Prussia than to Russia. His reign, when it came in 1762, was brief and disastrous. I watched, listened, and built allies in the army, the nobility, and the court. In July of that year, I took a bold and dangerous step: I overthrew Peter in a coup, with the support of the military. He was arrested and later died under suspicious circumstances. I became Empress of Russia—not by inheritance, but by will, cunning, and timing.

It was not enough to wear the crown. I had to earn it. I immediately set about stabilizing the government, rewarding loyalty, and presenting myself as the enlightened ruler Russia needed. I knew I had to appear strong, wise, and devoted to the Russian people. I studied statecraft relentlessly, wrote policy, and built a network of advisors, many of whom shared my love of Enlightenment philosophy. I read Voltaire, corresponded with Diderot, and imagined myself a philosopher-queen in the style of Plato.

Reform, Reason, and Rule

My reign was long—thirty-four years—and filled with contradictions. I modernized the Russian government and expanded its institutions. I attempted to codify laws, reform the bureaucracy, and improve education. I established the Smolny Institute, the first state school for girls in Russia, and encouraged literature, science, and medicine. I even convened a legislative commission to write a new law code, though it ultimately failed to achieve its goals.

At the same time, I relied on the nobility to maintain my power and suppressed rebellions with brutal force. The Pugachev Rebellion, led by a Cossack who claimed to be Peter III, reminded me how fragile authority could be. I crushed it, but I also strengthened serfdom in its aftermath. The ideals of liberty and justice that I admired in the writings of the French philosophes did not always match the realities of governing an empire as vast and diverse as Russia.

An Empire Expanded

I was not content to reform from within—I also expanded outward. Under my rule, Russia grew dramatically. I pushed southward against the Ottoman Empire, securing access to the Black Sea and founding new cities like Sevastopol. I annexed Crimea and supported Greek Orthodox Christians under Ottoman rule. I reached westward, participating in the partitioning of Poland, which brought large territories and millions of new subjects into the empire. My generals marched across the steppes and into the Caucasus. I made Russia a true European power, one to be respected—and feared.

The Private Empress

Behind the power, I was still a woman who craved intellect, passion, and connection. I had a series of lovers throughout my life—men who advised me, entertained me, and occasionally shared my political vision. I was not ashamed of this. I lived as I ruled: unapologetically and decisively. I built palaces, collected art, and filled my court with splendor. But I also worked tirelessly. I rose early, read reports, issued orders, and held audiences. I ruled not from ceremony but from action.

Legacy of a Tsarina

I died in 1796, having ruled for more than three decades. Some called me the “Enlightened Despot.” Others saw me as a usurper who betrayed Enlightenment ideals when they proved inconvenient. I see myself as a woman who took the tools of empire and used them to build something lasting.

I left Russia stronger, richer, and more educated than I found it. My successors would struggle to balance the forces I unleashed: modernization, expansion, and the thirst for freedom among a people long oppressed. But I had no regrets. I had ruled as few women ever had—with vision, force, and relentless ambition. And I had made Russia not only larger, but greater.

Empires Expanding: Russia, Britain, France, and Qing China – Told by Catherine

The world of my reign was not a quiet one. Across continents and oceans, the great powers of the world were moving, conquering, and trading with a hunger that had not been seen in previous centuries. Empires, vast and ever-hungry, were expanding their borders, testing each other’s strength, and reshaping the map. This was an age of conquest, but also of ideas, of Enlightenment rubbing shoulders with ambition. I, Catherine of Russia, was a participant in this expansion, a woman in a man’s world, ruling a nation built on strength and intellect. But I was not alone. Britain, France, and the Qing Empire in China were rising in their own ways—through war, diplomacy, trade, and reform.

Russia: Order Through Expansion

When I took the Russian throne in 1762, I inherited an empire already stretching from the forests of Poland to the frontiers of Siberia. But I intended to make it greater. I waged successful wars against the Ottoman Empire, pushing southward to claim access to the Black Sea. This was not merely for glory, but for commerce and power. With a warm-water port, Russia could trade year-round, expand its navy, and influence the Mediterranean. I founded new cities like Sevastopol and encouraged settlers to build farms, factories, and academies. We annexed Crimea and brought in new peoples—Tatars, Ukrainians, Armenians—each adding complexity to our empire.

But Russia also looked west. Through the three partitions of Poland, in alliance with Prussia and Austria, we took great swaths of territory and absorbed millions of new subjects. This was political surgery masked as diplomacy. We claimed order where chaos reigned, and in doing so, expanded our influence over Eastern Europe. I considered myself an enlightened ruler, yet I did not hesitate to use armies to ensure Russia’s destiny.

Britain: An Empire of Trade and War

While Russia expanded overland, Britain looked to the seas. The British Empire, built on its formidable navy and mercantile system, stretched across the Atlantic and into Asia. Between 1756 and 1763, Britain fought and won the Seven Years’ War, gaining control over Canada, vast territories in India, and dominance in the Caribbean. This war reshaped the global balance of power. Britain’s victory, however, came at a cost—one that would soon erupt into rebellion.

In 1776, the American colonies declared independence. Though a blow to Britain’s prestige, it did not cripple its empire. Britain quickly turned its attention to India and Africa, expanding trade routes and investing in the East India Company’s growing control over South Asian territories. Britain’s power was rooted not only in its colonies, but in its ability to finance wars, control shipping, and manipulate global markets. It was not merely a kingdom—it was a machine, relentless and far-reaching.

France: Glory and Trouble Abroad

France, our cultural cousin and rival, had once stood as the dominant power in Europe. But by the mid-1700s, she began to stumble. The Seven Years’ War had left France stripped of many of her overseas possessions, particularly in North America and India. Though French influence lingered in the Caribbean and West Africa, the loss of Quebec and Bengal was deeply felt. Yet, France remained ambitious. Her explorers moved into the Pacific, her traders roamed Africa and Asia, and her thinkers sparked revolutions of the mind.

It was within France that Enlightenment ideas burned brightest—and it was France that would be consumed by them. By the 1780s, her economy strained under debt and her people grew restless. Even as the empire held on abroad, the monarchy weakened at home. Still, one cannot ignore France’s continuing influence: her language, fashion, and philosophy spread like perfume across Europe. While Britain ruled the seas, France ruled the salons.

Qing China: The Middle Kingdom Standing Strong

Far to the east, the Qing Dynasty ruled over the largest and most populous empire in the world. Under emperors such as Qianlong, China reached its territorial height, incorporating Tibet, Xinjiang, Mongolia, and much of Central Asia. The Qing court was stable, sophisticated, and proud. China’s economy flourished, fueled by tea, porcelain, and silk. Merchants from Europe flocked to Canton, desperate to exchange silver for the luxuries of the East.

And yet, China stood apart from our European empires. The Qing viewed themselves as the center of civilization, and they resisted many of the changes sweeping across Europe. They imposed strict controls on trade, limited foreign access, and dismissed Western diplomatic overtures. I admired China’s order and longevity, but I also saw the signs of resistance to innovation. Their strength was real—but it was built on foundations that would later be tested.

A World Redrawn

Between 1750 and 1790, the world was being redrawn—not just with borders and flags, but with ideas and systems. Empires grew, yes, but so did tensions. Expansion came with cost: rebellion, debt, resistance, and the strains of governance. I ruled a land of vast distances and many peoples, balancing reform with control. Britain and France danced between dominance and instability. China held firm to tradition while the world shifted around it.

It was a time of splendor and of shadow, of ambition cloaked in civilization. We, the monarchs and ministers, saw ourselves as architects of greatness. But the people, the thinkers, and the markets—these forces were beginning to move beyond our grasp. Expansion brought power, but it also sowed the seeds of change. The empires we built would not last forever, but the world they created would shape the centuries to come.

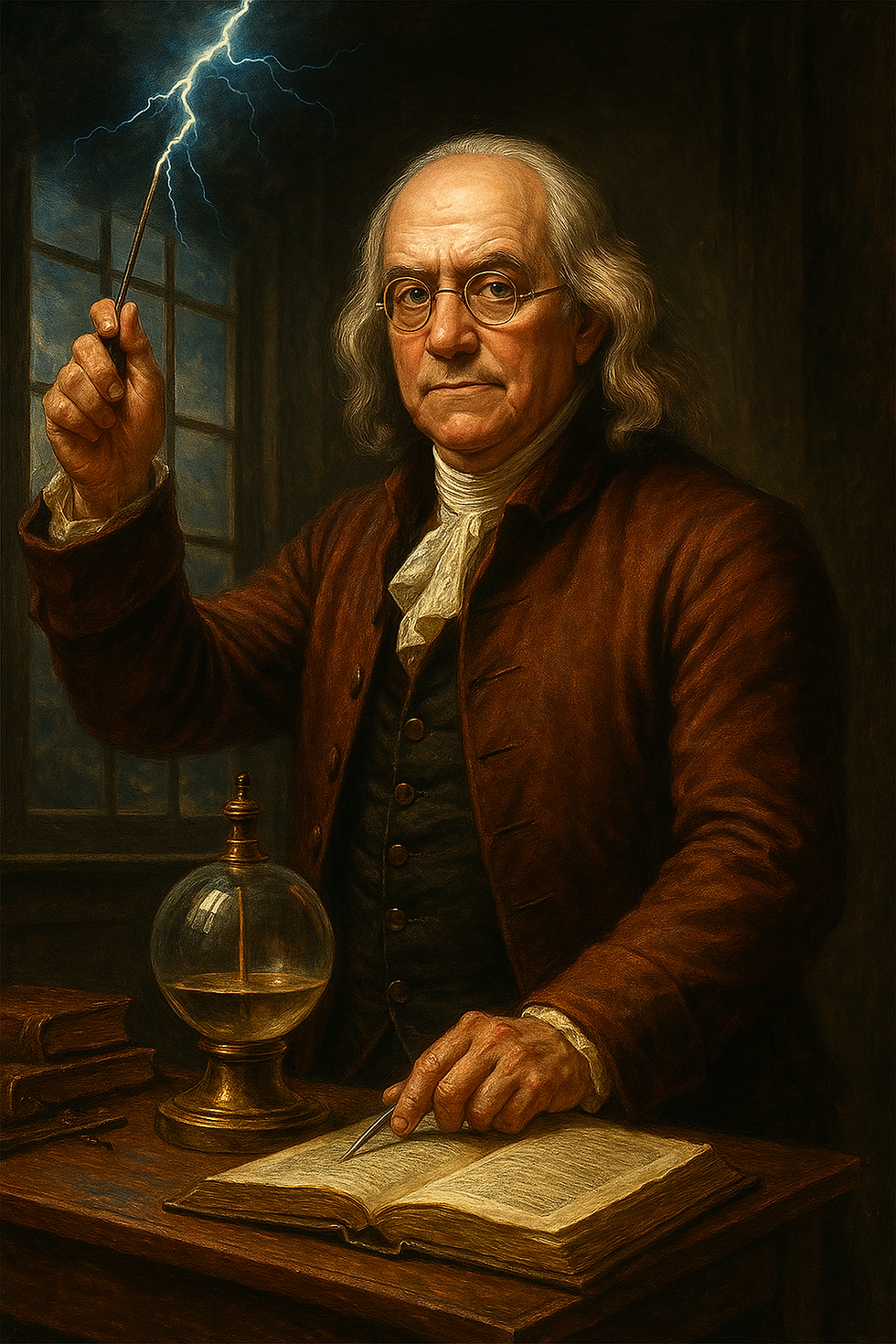

My Name is Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790): My Many Lives

I was born in Boston in 1706, the fifteenth child in a family of seventeen. My father, Josiah Franklin, was a candlemaker and soap boiler, and there wasn’t much money to go around. Still, I was blessed with a curious mind and an eagerness to read whatever I could find. My formal education ended at the age of ten, but I took to learning on my own. At twelve, I was apprenticed to my older brother James, a printer. It was there in the printing shop that I first tasted the power of the written word. I secretly wrote letters to the newspaper under the pen name Silence Dogood, pretending to be a witty widow. Readers enjoyed her, though my brother was furious when he discovered her true identity.

Finding My Way in Philadelphia

At seventeen, I ran away from Boston, tired of my brother’s harsh hand and eager to make something of myself. I arrived in Philadelphia, bedraggled and penniless, with nothing more than a strong work ethic and a desire to learn. I found work as a printer and quickly gained a reputation for being industrious and clever. I even traveled to London to expand my trade but returned to Philadelphia wiser and more determined. Eventually, I set up my own printing shop and published Poor Richard’s Almanack, where I wrote under yet another pseudonym. The almanac became a household favorite, filled with proverbs, humor, and advice, much of which still echoes in American ears today.

Building a Better Society

But I was not content with personal success alone. I believed deeply in civic virtue and public service. I helped establish the first public library in America, organized a fire company, improved street lighting and sanitation, and co-founded what would become the University of Pennsylvania. I believed that knowledge should be shared, that communities should look after one another, and that every man should rise by merit, not birthright. I also founded the American Philosophical Society, a place where ideas could be exchanged freely and wisely.

The Spark of Science

My curiosity didn’t stop at words and politics—it reached into the natural world. I devoted myself to the study of electricity and conducted experiments that gained attention around the world. Most famously, I flew a kite in a thunderstorm to prove that lightning was a form of electricity. The experiment was dangerous, yes, but enlightening. I went on to invent the lightning rod, bifocal glasses, and the Franklin stove. I never patented my inventions. I believed that knowledge, once found, should be shared freely for the benefit of all.

Defending Liberty Abroad

As tensions rose between the American colonies and Britain, I was called upon to serve as a diplomat. In 1757, I sailed to London to represent the colonies’ interests, and I remained there for many years, trying to prevent conflict. But the British government was unwilling to treat us fairly. When war became inevitable, I returned home and helped draft the Declaration of Independence. Then I set sail once again—this time to France, where I worked to secure vital military and financial support for our revolution.

My time in France was perhaps my most unusual chapter. I dressed plainly, spoke of liberty, and won the hearts of the French people. I moved among nobles and philosophers, building alliances not only with armies but with minds. Without France, our victory would have been unlikely. I am proud to say I helped bring that alliance to life.

The Constitutional Years

After the war, I returned to Philadelphia, older and more worn, but still devoted to public service. I served as President of Pennsylvania’s Supreme Executive Council and later took part in the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Though illness made it hard to speak, I urged my fellow delegates toward compromise and unity. I supported the new Constitution—not because it was perfect, but because it was a start. As I told the assembly, “I consent, Sir, to this Constitution because I expect no better, and because I am not sure that it is not the best.”

A Life in Full

I died in 1790 at the age of 84. More than twenty thousand people attended my funeral in Philadelphia, a testament not to wealth or title, but to a life spent in service, inquiry, and reflection. I was many things: a printer, a writer, a scientist, a diplomat, an inventor, a philosopher, and a statesman. But above all, I was a citizen—a believer in the power of human reason, in the dignity of labor, and in the pursuit of liberty.

I began in obscurity, rose through curiosity and effort, and never ceased to believe that a better world was possible. I lived not for applause but for improvement. And if I am remembered, let it be for this: I tried to leave the world wiser, warmer, and freer than I found it.

Science and the Spinning World: Discovery and Exchange – Told by Franklin

In the decades between 1750 and 1790, the world began to turn faster—not only on its axis, but in the minds of men. It was an age not just of machines and markets, but of questions, experiments, and astonishing answers. The early Industrial Revolution is remembered for its spinning frames and steam engines, but I remember it equally for what was happening in the study rooms, laboratories, and correspondence of curious souls around the globe. We were living in the age of inquiry, when reason and observation began to replace superstition and tradition. And what a time it was to be alive.

I was fortunate to be among the many who contributed to the advancement of knowledge. Though I never claimed to be a scientist in the formal sense, I was drawn to nature’s puzzles. What caused lightning? How could we harness energy more safely? How did electricity behave, and might it serve mankind? These were the sorts of questions that drove my kite into a stormy sky and brought sparks to a key—an experiment that, by Providence and good fortune, did not end my life prematurely.

Electricity and Enlightenment

Electricity was a subject of endless fascination during my lifetime. I conducted numerous experiments in Philadelphia and shared my findings with friends across the Atlantic. I discovered the principle of positive and negative charge and coined terms still used in electrical studies today. I learned that lightning and electricity were one and the same and helped introduce the lightning rod, a simple device that has saved countless homes and churches from destruction.

But I was not alone in this field. Men like Joseph Priestley and Luigi Galvani were also exploring the strange force of electricity. In Germany, physicists pondered magnetism. In France, the chemists made advances in gases and combustion. The scientific community was not bound by borders. We wrote to one another, sent specimens and instruments, and translated each other’s findings. In this way, the Royal Society in London, the Académie des Sciences in Paris, and our own American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia became hubs of a vast and growing web of learning.

From Invention to Industry

While philosophers and naturalists studied the heavens and elements, a different kind of genius turned his attention to industry. James Watt in Scotland improved the steam engine, building upon earlier designs to create a machine that could power factories, pumps, and ships. This advancement, though mechanical, was deeply rooted in scientific understanding—of pressure, heat, and motion. In England, men like John Kay and Richard Arkwright developed looms and spinning machines that transformed the textile trade. The very notion of work was being redefined.

These inventions did not stay put. They crossed oceans as quickly as letters. Drawings and models were shipped to America. French engineers studied British designs. Indian and Chinese scholars observed Western machinery with both interest and caution. Knowledge became a form of trade—exchanged not only in universities and salons, but on ships, at ports, and along the great arteries of empire.

The Spirit of Collaboration

What strikes me most about these years is the spirit in which knowledge was shared. Yes, some guarded their discoveries for profit, but many more believed that science was a common inheritance. I myself never patented my inventions. Whether it was the Franklin stove or bifocal spectacles, I thought it better that others should benefit freely. This was, to me, the proper application of science: to improve the conditions of ordinary life.

In France, I met with thinkers like Lavoisier, who studied the chemistry of air and fire. In England, I dined with astronomers and engineers. These meetings were not mere formalities—they were exchanges of insight. A gentleman might bring an insect from India, a mineral from the Andes, or a puzzle from a faraway land, and we would all gather to observe and discuss. It was thrilling, to see the world unfold in this way—piece by piece, through the eyes of many nations.

Knowledge as a Global Currency

As the empires of Europe spread, so too did ideas. Missionaries brought telescopes as well as scriptures. Merchants carried books along with bolts of silk. Even colonists, though often seeking fortune, brought learning with them. The world was becoming more interconnected, not just by trade routes and treaties, but by understanding. We began to recognize the natural laws that governed all lands and peoples, regardless of language or skin.

Still, it must be said—this exchange was not always equal. Much of the knowledge traveled outward from Europe, and too often the wisdom of native peoples was ignored or suppressed. In truth, every land has its own sciences, its own insights, and we would have done better to listen more closely. Even so, I believe that the foundation was laid for a more shared pursuit of knowledge in the generations to follow.

Science for the Good of All

As I reflect on my life and my times, I am filled with hope. Not because every problem has been solved, or every injustice corrected—but because the tools for progress have been placed in human hands. We now understand that through careful study and free exchange of knowledge, we can improve health, invent new tools, protect our homes, and lift the burdens of labor.

The early years of the Industrial Revolution were only the beginning. The machines and discoveries of my time will multiply. But I pray that the spirit behind them—the spirit of curiosity, generosity, and reason—will grow even faster. For in the end, science is not a cold thing. It is the fire of the human mind, lit by wonder, and passed from one hand to another. And it is that fire which will light the way ahead.

Rebellion, Liberty, and the Ripples of Revolution – Told by Benjamin Franklin

When I was a younger man, I considered myself a loyal subject of the British Crown. I lived in London for many years, dined with members of Parliament, and believed that with a little wisdom and good sense, the relationship between Britain and her American colonies could be made more just. But over time, I came to see that the mother country did not view us as equals. We were to be ruled, taxed, and kept in our place—despite contributing men, goods, and loyalty to the empire. The Stamp Act, the Townshend Acts, and finally the Coercive Acts were proof that something had changed. The colonies were growing stronger, more populous, and increasingly confident. Yet our voices were ignored. I went from peacemaker to revolutionary not out of anger alone, but out of deep disappointment.

Declaring Independence

When the time came to stand with my fellow countrymen in defiance, I did so not with rage, but with resolve. In 1776, I helped draft the Declaration of Independence alongside Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and others. It was not just a severing of ties—it was a statement of belief: that all men are created equal and endowed with unalienable rights. This idea, though ancient in spirit, had never been so boldly written into the founding of a new nation. We were not just fighting for land or laws. We were fighting for a new principle—that governments derive their power from the consent of the governed.

Revolution and Diplomacy

While others took up arms, I took up the pen and the passport. I was sent to France to secure support for our cause. It was a difficult task—asking a monarchy to support a republic—but I wore my plain American dress, spoke earnestly of liberty, and found willing allies among the French. Their support in ships, men, and money helped tip the balance in our favor. The American Revolution was not fought alone. It was a global event. France, Spain, and the Netherlands entered the fray, turning our colonial rebellion into a worldwide conflict. Even the British, stretched thin, began to feel the cost of global empire.

The Shockwaves Abroad

What many did not expect, and what I quietly hoped, was that our revolution would not end at our shores. The ideas we declared—the rights of man, the limits of tyranny, the power of a free people—began to stir hearts across Europe and beyond. In France, young thinkers and commoners alike took inspiration from our example. I knew men who once toasted kings who now began to speak of constitutions. The American Revolution showed that Enlightenment ideals were not just for books and salons—they could guide a nation.

In Haiti, enslaved people heard of liberty and took courage. In Latin America, young criollo leaders would one day read our words and begin their own movements for independence. Even in Britain, there was deep debate over the justice of the war and the rights of citizens. Our cause may have been American, but its spirit was universal.

An Industrial Age Awakened

Now, you may ask, what does any of this have to do with the spinning jennies and the steam engines that were beginning to reshape the world? The answer is this: the American Revolution was not merely a political event—it was a cultural and economic turning point. It affirmed the value of individual rights, property, and innovation. It cleared the way for new markets, new governments, and new freedoms that allowed enterprise to flourish. When America broke free, it did not just create a new nation—it created a new kind of economy. One where merchants were not bound by royal charters, where invention was not limited by guilds, and where people were free to rise by merit.

The Industrial Revolution needed fuel—not just coal and iron, but bold ideas. It needed freedom of thought, freedom to experiment, and freedom to profit from one’s labor. The American example gave many the hope that such freedoms were not only possible, but worth fighting for.

A Global Turning Point

By the time I drew my final breath, I could see that the world had changed. The old order of kings and empires was still standing, but its foundations had been shaken. A republic had been born. A new kind of citizen had emerged. And across the globe, men and women were beginning to believe that their lives could be governed not by birth, but by reason and justice.

The American Revolution was not the final word—it was the first sentence of a new chapter in world history. A chapter where ideas could move faster than armies, where liberty could travel farther than empires, and where the engines of change—political and industrial—would reshape the world.

I was proud to have lived in such a time, and prouder still to have played a part in it. May those who come after me remember that freedom is not the absence of struggle, but the triumph of principle over fear. And may they use that freedom wisely, in both the making of nations and the making of machines.

The Imperial Gaze: Colonialism Across Continents – Told by Catherine the Great

The world in which I reigned was not one of stillness, but of motion—of ships crossing oceans, armies marching across frontiers, and traders carving paths into distant lands. The age from 1750 to 1790 was an age of empires reaching outward with eager hands. Though I ruled Russia, and my empire stretched far across the frozen steppes and southern frontiers, I could not ignore the immense wave of colonial expansion sweeping through Asia, Africa, and the Americas. It was an age where Europe pressed its will upon the world, cloaked in the language of civilization, commerce, and discovery.

The Americas: Dominion and Resistance

Across the Atlantic, the European powers carved the Americas into zones of influence and profit. The Spanish and Portuguese had long claimed dominion over much of the continent, but by the mid-1700s, the British and French had joined the contest with vigor. The Caribbean islands were the crown jewels of empire—not because of size, but because of sugar. That sweet substance, grown by enslaved Africans under brutal conditions, brought fortunes to European merchants and misery to millions.

North America, meanwhile, became a battleground of ideas and armies. The British, having won Canada from the French in the Seven Years’ War, now ruled a vast and diverse territory. But rule bred resistance. When the American colonists declared independence in 1776, they did more than reject taxes—they rejected the notion that an empire had the right to govern without consent. I watched this revolution unfold with great interest. It was the first true crack in the imperial order. And yet, elsewhere in the Americas, colonial rule remained firm, upheld by violence, trade, and rigid hierarchies of race and class.

Africa: A Land Exploited

In Africa, the European presence was concentrated along the coasts. Britain, France, Portugal, and the Dutch established trading posts from Senegal to Angola—not to cultivate empire in the traditional sense, but to extract people. The transatlantic slave trade was still in full force. Ships sailed from European ports to African coasts, where human beings were purchased, branded, and loaded like cargo to be sold in the Americas.

It is a truth difficult to look upon, yet impossible to ignore. Africa, rich in its own civilizations, resources, and cultures, was not seen as a land of equals, but as a well of labor for plantations and mines. Though some African leaders participated in the trade, many more were victims of betrayal, war, and capture. This extraction of life weakened kingdoms, disrupted communities, and altered the continent’s future for centuries. And all the while, the European powers grew wealthy on the backs of those they enslaved.

Asia: Empires of Trade and Subjugation

In Asia, the story of colonialism was one of trade turned into power. The British East India Company, which began as a commercial venture, had become a military and political force in India by the mid-18th century. After the Battle of Plassey in 1757, the Company effectively ruled Bengal, and from there expanded its influence across the subcontinent. It was not the British crown that conquered India—it was merchants. Soldiers followed silver, and governors followed sugar and cotton.

The French, too, had interests in India, though their influence waned after their losses to Britain. In Southeast Asia, the Dutch held sway over the spice islands, and Spanish rule endured in the Philippines. China and Japan, ancient and powerful, resisted colonial domination, but European merchants found their way in through trade ports, treaties, and diplomacy. It was not full conquest, but it was a form of intrusion all the same.

The Russian View Beyond Our Borders

As Empress of Russia, I did not engage in overseas colonialism as Britain, France, or Spain did. My empire expanded by land—into Central Asia, across Siberia, and into Eastern Europe. Still, I observed these global developments with a scholar’s eye and a sovereign’s interest. I corresponded with thinkers who debated the morality and utility of empire. I read about the indigenous peoples of the Americas, the kingdoms of Africa, the cities of India and China. And I understood that colonialism was not simply about geography—it was about control, ideology, and the reshaping of the world’s people into the image of the powerful.

A Global Order Built on Uneven Ground

By the end of my life, Europe had imposed itself upon much of the globe. Colonial rule brought new technologies, institutions, and ideas—but it also brought disruption, displacement, and violence. It was not a one-sided story, for in every colony there were moments of resistance, preservation, and survival. The colonized were not merely subjects; they were actors in a long, difficult struggle to maintain dignity under foreign rule.

Colonialism reshaped the economies of the world, tying distant lands into webs of trade that served the centers of empire. Cotton grown in India clothed the people of London. Sugar from the Caribbean sweetened the tea of Paris. African gold flowed into European banks. It was a system that enriched a few and burdened the many.

The Future Beyond Empire

I do not pretend to have solved the riddle of empire. I ruled one of the largest empires in history, and I expanded its reach with a firm hand. Yet I also believed in reason, education, and the possibility of just rule. I watched as revolutions erupted, ideas spread, and people questioned whether empires could last forever.

Colonialism, in its many forms, was the defining force of the age. But the world would not remain divided into masters and subjects forever. New voices were rising—from Philadelphia to Port-au-Prince, from Calcutta to Cairo. I suspected, even then, that a storm was gathering. And while I sat on a throne, I could not help but wonder what kind of world would rise when the winds of empire began to shift.

A Woman on the Throne: Role of Women in a Changing World – Told by Catherine

I was born in 1729 as a minor German princess, never imagining I would one day rule the Russian Empire. In the world I entered, women were expected to serve quietly—at court, in the home, or in convents. We were educated just enough to charm, marry, and obey. Yet from a young age, I saw that obedience would not serve me. If I were to survive and thrive, I would need to observe closely, think deeply, and act boldly. That, I believe, is what all women of my time were beginning to realize—not just those born in palaces, but those who lived in parlors, markets, and villages. The world was changing. And women, though long confined, were beginning to press against the walls.

Enlightenment and the Female Mind

The Enlightenment was a storm of ideas—reason, liberty, science, and progress. It swept through salons in Paris and libraries in London. It touched universities, coffeehouses, and courts. And it stirred the minds of women. While men published treatises and debated in academies, women read in secret, hosted salons, and wrote under pseudonyms. We were not merely witnesses to this age of reason—we were participants, often unacknowledged but ever present.

In France, women like Madame Geoffrin and Madame de Staël led intellectual circles. In England, Mary Wollstonecraft would soon write her bold defense of women's rights. Even in my own empire, noblewomen took an interest in education, philosophy, and literature. The idea that women were incapable of deep thought was losing its grip, though not without resistance. Still, society moved slowly. For every voice like mine raised in leadership, there were thousands more silenced by tradition.

Education: The Gate to Progress

I believed that education was the true key to lifting women—and indeed all people—from ignorance and dependency. One of my proudest reforms was the founding of the Smolny Institute, Russia’s first state school for girls. It was a modest step, but it marked a new vision. Women should not be taught merely how to sew and pray. They should be taught to read, to reason, and to contribute to society with confidence and intelligence.

Across Europe and its colonies, similar ideas began to take root. Female education was still rare, but its value was increasingly recognized by those who understood the link between knowledge and power. Enlightenment thinkers often spoke of natural rights and equality, yet many hesitated to include women. That was their blind spot. But women were learning, remembering, and waiting.

Work, Family, and Social Shifts

In the countryside and among the working classes, women had always labored—on farms, in homes, in markets. Their role was essential, though rarely celebrated. During this period, as industry began to rise in Britain and elsewhere, women’s labor shifted. In textile mills, print shops, and small factories, women worked long hours for little pay. They earned wages, but rarely independence. The world relied on their work, but offered little in return.

In wealthier households, women played the roles of hostesses, companions, and mothers. They were the keepers of reputation, the stewards of domestic life, and often the quiet managers of estates. Some held great influence over husbands, sons, and courts. Others suffered in silence. I myself was born into this world—but I refused to be defined by it.

A Woman on the World Stage

When I seized power in 1762, I did so as a woman in a man’s world. Many questioned my legitimacy, my intellect, my ability to rule. I answered with policy, diplomacy, and endurance. I expanded the empire, reformed institutions, and corresponded with the greatest minds of Europe. I proved that a woman could command armies, build cities, and shape the destiny of millions. Yet even I, an empress, was judged by my appearance, my relationships, and my gender in ways no man ever was. I do not complain—I prevailed—but I never forgot how narrow the path was for women.

Change Begins with Possibility

The period from 1750 to 1790 did not liberate women—but it planted the seeds. Women began to see themselves as citizens, thinkers, and individuals with rights. The American Revolution spoke of liberty, and women there asked, “What of us?” In France, before the storm broke, women demanded to be heard. In Russia, I stood as proof that women could rule not just households, but empires.

Yet I knew the world would not change overnight. Progress, like empire, must be built step by step. I encouraged education, allowed greater access to literature, and supported reforms that opened doors—if only slightly—for women of my time.

The Legacy We Leave Behind

I leave this world knowing that the struggle for equality continues. But I also know that change begins when someone dares to imagine it. From the salons of Paris to the fields of England, from the printing presses to the throne of Russia, women were beginning to rise—not in rebellion alone, but in reason, resilience, and quiet determination.

If my reign showed anything, it is that the mind has no gender, that wisdom is not the property of men, and that a woman with vision can shape the world as surely as any man with a sword. The role of women was changing in my time—not quickly, not fully, but undeniably. And it would continue to change, for history does not stand still, and neither do we.

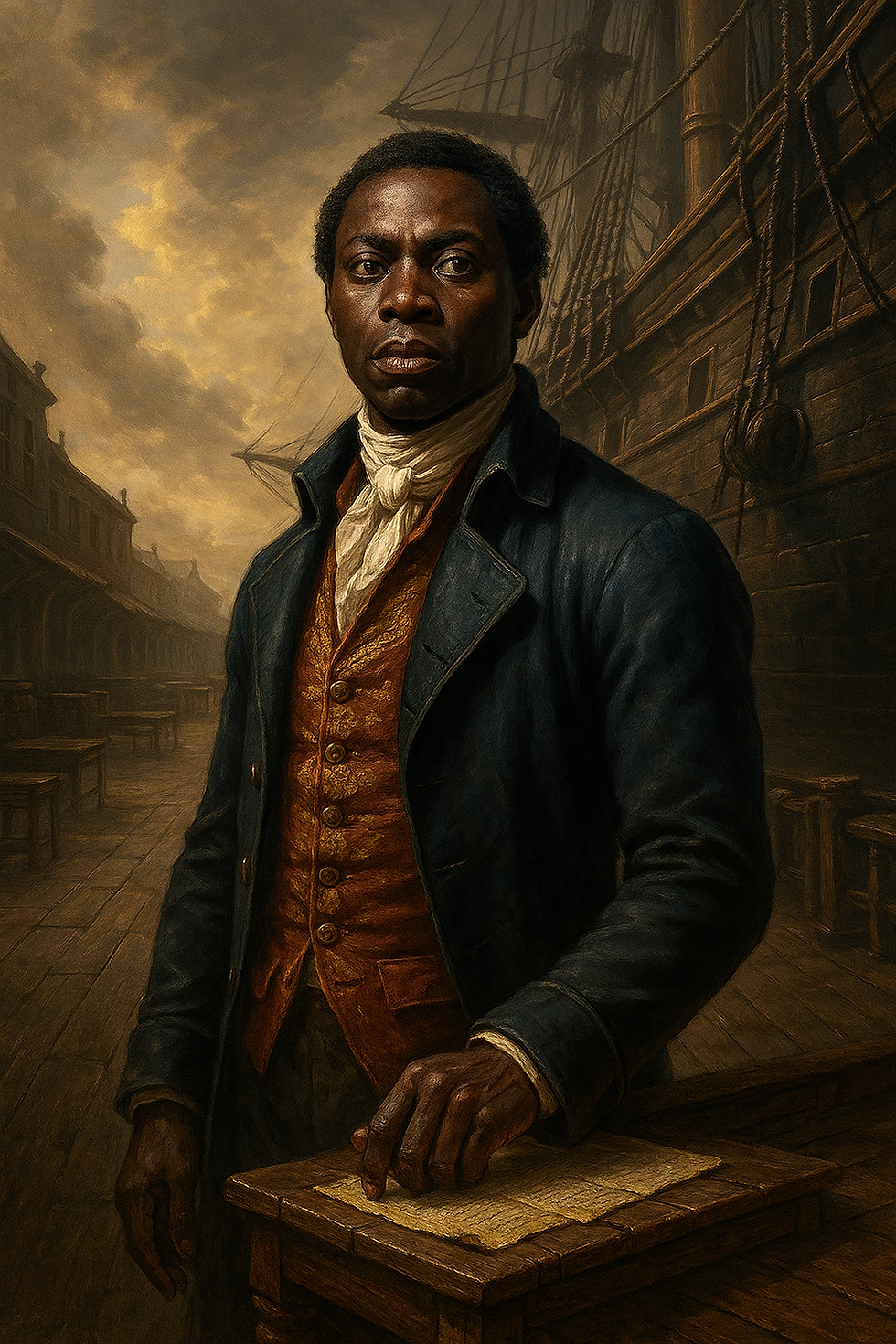

The Transatlantic Slave Trade and Resistance – Told by Olaudah Equiano

I was born in the land of the Igbo, in what is now Nigeria, and I lived as a free boy among my people until I was about eleven years old. My days were filled with family, language, tradition, and the rhythm of village life. But that world was ripped away from me in an instant. Raiders attacked our village, and I was taken—tied, marched, and sold, first to African traders, then to Europeans. I did not understand the language of my captors or the fate that awaited me. I only knew fear and confusion as I was brought to the coast and placed aboard a ship that would cross the ocean to a world I could not imagine.

The ship that carried me was packed tight with human bodies—men, women, and children, shackled in chains, groaning in despair. The stench was unbearable, and the cries of the dying echoed day and night. This was the Middle Passage, one part of the vast transatlantic slave trade, a system that moved not just goods, but lives—millions of them—between Africa, the Americas, and Europe. It was not merely commerce. It was cruelty institutionalized.

The Machinery of Oppression

Between 1750 and 1790, the slave trade reached terrible heights. Ships sailed from Europe loaded with textiles, firearms, and liquor, which were traded in Africa for people—people who were kidnapped, sold, or betrayed into bondage. Those who survived the passage were taken to the Caribbean, to North and South America, where they were sold into labor on plantations of sugar, cotton, and tobacco.

The labor was relentless. On sugar plantations in the West Indies, enslaved Africans worked under the whip, in scorching heat, suffering disease, injury, and death in staggering numbers. The trade was profitable to European merchants and plantation owners. It built the wealth of nations while destroying the bodies and cultures of others. Every person carried across the ocean was a life uprooted, a language lost, a name replaced, and a history broken.

My Struggle for Freedom

I was sold into bondage more than once. At sea, I learned to sail, to read, and eventually to negotiate. After years of service aboard British ships, and through extraordinary fortune and persistence, I purchased my freedom. But even as a free man, I could not forget what I had seen, nor the countless others who remained in chains. I began to write and speak, to tell the story not only of my life but of the entire system of injustice that had brought me across the Atlantic.

In 1789, I published The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. It was a plea for justice, a testimony of survival, and a weapon in the growing movement to abolish the slave trade. My words reached the eyes of lawmakers, citizens, and fellow abolitionists, and I hoped they would stir hearts to action.

Resistance Across the World

We did not go quietly. Resistance took many forms. On ships, enslaved Africans rose up, seizing weapons and attempting to take control. These rebellions were often crushed with brutal force, but they showed the spirit that refused to submit. In the Caribbean, revolts erupted—some small and scattered, others large and terrifying to the slaveholders. One could feel that something greater was coming. In the French colony of Saint-Domingue, whispers of rebellion stirred among the enslaved. Soon, those whispers would rise into the thunder of revolution.

Even in the British colonies and across Europe, voices were raised in protest. The Quakers spoke early against slavery, and men like Granville Sharp and Thomas Clarkson began to gather evidence and testimonies, turning conscience into campaign. Women, too, played a crucial role—organizing, writing, and refusing to purchase sugar grown by slaves. This was not only a battle fought with chains and ships—it was fought with books, petitions, and words.

The Tide Begins to Turn

By the end of the 1780s, a powerful movement had formed in Britain. I was honored to stand among the abolitionists, to speak in public, to meet with those in Parliament. We knew the fight was not yet won, but change was stirring. For the first time, the slave trade was being debated not as an economic tool but as a moral crime. The world had long accepted slavery as normal. Now, it was being forced to justify the unjustifiable.

Still, millions remained enslaved, and the trade continued. Resistance was not always successful, and laws moved slower than ships. But we believed—no, we knew—that truth had power. That dignity could not be erased, and that even those born in bondage could rise to speak, to write, and to demand the freedom that is the right of every soul.

Memory and Hope

I lived to see the beginnings of change, though not its completion. The British slave trade would not be abolished until after my death. Slavery itself would endure into the next century. But I have hope, because I saw the moment when the world began to listen.

I tell this story not to recount sorrow alone, but to show that resistance is always possible. That in every corner of suffering, there is someone who dreams of freedom. And that no matter how wide the ocean, how cruel the master, or how deep the pain, the human spirit endures. Let my voice be one among many. Let my life, stolen and reclaimed, remind all who hear it that justice delayed is not justice denied.

Cultural Diffusion Through Trade, Exploration, and Conflict – Told by Olaudah I was born in a land rich with its own traditions, languages, and beliefs. In my village in West Africa, we honored our ancestors, told stories under the stars, and lived by customs handed down through generations. But when I was taken, when I was sold into the machinery of the slave trade and thrust into the world beyond my homeland, I encountered something I could never have imagined—a world constantly in motion, where people, goods, ideas, and even faiths traveled across seas and continents. Much of this was driven by trade, exploration, and war. Some of it brought opportunity, but much of it brought suffering. And yet, amidst the pain, cultures met and transformed each other in ways no power could fully control.

A World of Trade and Exchange

Trade was the great engine of the age. Across the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, ships crisscrossed the waters carrying sugar, cotton, spices, silver, tea, coffee, tobacco, and more. Alongside these goods came languages, technologies, clothing, food, and habits. European merchants brought textiles to Africa, where they were exchanged for human lives. Slaves were sent to the Americas, where they labored on plantations to produce goods that fed Europe's growing appetite. In the markets of the West Indies, I saw African patterns worn by Caribbean women, European tools used by indigenous hands, and languages that blended words from many lands.

Even as a slave, I witnessed this mix of cultures firsthand. On British ships, I heard English, French, Spanish, and African dialects spoken together. In the Caribbean, enslaved Africans found ways to preserve their identity—through music, food, dance, and belief—blending their traditions with those of others around them. This was cultural diffusion born not of curiosity, but of necessity and survival. We did not simply adopt new customs—we reshaped them.

Exploration and the Reach of Empire

Europe’s thirst for exploration pushed its powers into the farthest corners of the world. The British and French sailed to India and China. The Spanish ventured deeper into the Americas. These journeys were often claimed in the name of knowledge or progress, but they were also missions of conquest. Where explorers went, empires followed. Still, every encounter left a mark. European botanists studied Asian plants. African navigators taught Europeans the paths of coastal waters. American crops such as maize and potatoes transformed European diets.

These exchanges, however uneven, changed the shape of daily life around the world. In West Africa, firearms brought by Europeans altered warfare. In Europe, tea from China became a daily ritual. In the Americas, African drums, rhythms, and songs became the foundation of new musical traditions. Exploration opened new trade routes, but it also opened channels for the movement of ideas, resistance, and adaptation.

Conflict as a Carrier of Culture

Where trade and exploration did not reach, conflict often did. The Seven Years’ War, fought across Europe, the Americas, Africa, and Asia, was more than a clash of empires—it was a vehicle for cultural contact. Soldiers from different lands encountered new ways of living. Colonies changed hands. Territories were redrawn. In every occupied town, in every garrison, people met across boundaries of language and nation. Though war brought destruction, it also forced interaction. People absorbed foreign customs, languages, and strategies. Some of these changes were permanent, woven into the cultural fabric of regions far from the original conflict.

In the Americas, conflict led to revolution. When the American colonies rebelled against Britain, their ideas of liberty were not theirs alone. They had drawn upon Enlightenment thinkers from Europe and watched resistance movements across the globe. And when they declared independence, others were watching them. In the French colonies, in Haiti, and even among enslaved people in British holdings, whispers of freedom took root. The words of revolution did not stay on parchment. They traveled, ignited imagination, and stirred hope.

Faith, Food, and the Memory of Home

Throughout my travels, I saw cultural diffusion not only in great events, but in the quiet ways people lived. African foods—okra, yams, black-eyed peas—found their way into American kitchens. Religious beliefs mingled, forming new spiritual paths that drew from African, Christian, and indigenous roots. In slave quarters, songs passed from elder to child carried memories of homelands lost but not forgotten. Even in bondage, people kept parts of themselves alive by reshaping the world around them. We did not merely accept foreign ways—we adapted them to speak our truths.

I too was changed. I learned to read and write in English. I converted to Christianity and saw in it both sorrow and hope. I came to understand the power of the printed word, of European ideas about liberty, of African strength, and the potential of a shared world. My very life became a blending of continents and cultures—forced, yes, but also resilient.

The Cost and the Gift of Contact

The cultural exchange of this era came at great cost. It was not fair or balanced. Much of it was built on conquest, slavery, and greed. But amidst the suffering, people found ways to communicate, to preserve, and to create. The world grew smaller, more connected, and more complex. Empires thought they could control this process, but culture, once released, cannot be owned. It spreads like water, finds new shapes, and flows through every crack.

I lived in an age where I saw the best and worst of human contact. I saw cruelty born of trade, and compassion born of shared faith. I saw African songs sung in Caribbean fields, and Enlightenment ideals echo in the hearts of former slaves. I saw the beginning of something larger than any one nation.

Let it be remembered that even in the darkest systems, the light of human spirit crosses boundaries. The meeting of cultures is not only a tale of domination, but of endurance and transformation. And in that truth, there is great power.

Global Shifts in Power and the Foundations of Modern Nations – Told by Benjamin

The world I was born into in 1706 was governed by kings, empires, and the belief that authority came from above—by bloodlines or divine right. But by the time I reached the end of my life in 1790, the world had begun to awaken to a different idea. The Enlightenment had whispered to us that power might lie not in crowns but in reason, not in thrones but in the consent of the governed. And by the mid-18th century, those whispers began to thunder. From Europe to the Americas, the foundations of old powers began to tremble, and the seeds of modern nations were sown—not always peacefully, but with a force no empire could ignore.

The Shifting Empire of Britain

Britain stood as one of the most powerful nations in the world during my lifetime. With colonies stretching across the Americas, Africa, and Asia, it commanded the seas and governed distant peoples with a mixture of trade, law, and musket. But as its influence grew, so too did the weight of its burdens. After the costly Seven Years’ War, Britain sought to tax its American colonies to pay for imperial defense. This decision, born from logic, ignited resistance. When we colonists rose in protest, demanding rights equal to those of Englishmen, we did not intend to topple an empire—we merely wished to be heard. But when our voices were silenced, revolution followed.

The American War of Independence was not only a colonial rebellion. It was the beginning of a great shift in the structure of global power. We had shown that a colony could rise against the empire and survive. The victory of the United States was more than a military triumph—it was a political earthquake. Monarchs across Europe watched with unease. What if others followed our example?

France and the Shadow of Revolution

France, Britain’s greatest rival, had suffered defeat in the Seven Years’ War and lost much of its overseas empire. Yet while it rebuilt, it also simmered. The French people bore the weight of war debts, rising prices, and a deeply unequal society. And even as French nobles lived in luxury, Enlightenment ideas spread among the people. I spent many years in Paris, and I could feel it in the salons and coffeehouses—a quiet questioning, a boldness in speech. They had read our Declaration. They saw that we had forged a nation without a king. And they began to imagine doing the same.

Though the French Revolution would erupt fully after my death, its roots were nourished during this period. France was not merely shifting its own political ground—it was stepping toward the modern idea of nationhood, where people rather than monarchs would define the state.

Colonial Resistance and Future Nations

While the great powers of Europe fought and schemed, in the colonies across the world, resistance was taking shape. In Haiti, enslaved men and women heard of liberty and began to whisper of uprising. In Latin America, criollo elites began to chafe under Spanish rule. Though their revolutions would come later, they were already looking to the American experiment for guidance. The idea that a people could break free, govern themselves, and write their own constitution was no longer a fantasy—it was a precedent.

In India, the British East India Company tightened its grip after victories in Bengal, but even there, the structure of power was changing. The British were no longer just traders—they were rulers, administrators, builders of empire. Yet with each conquest came the possibility of resistance, and the slow rise of nationalist sentiment. In the decades to follow, these regions too would challenge foreign rule and envision their own future nations.

Russia and the Continental Balance

While Western Europe shifted under the weight of revolution and reform, Eastern powers like Russia, under Empress Catherine, expanded in influence. Catherine brought Enlightenment ideas to her court while extending her empire’s borders through war and diplomacy. She corresponded with philosophers and debated reforms, yet ruled with absolute authority. Her Russia was a symbol of both old and new—a place where the seeds of modern governance were sown within the soil of monarchy. Nations like Russia, Prussia, and Austria sought to maintain the old order, yet even they could not escape the changing world.

Ideas That Reshaped the Map

What truly caused the global shift in power between 1750 and 1790 was not only the movement of armies or the rise and fall of kings—it was the spread of ideas. The Enlightenment, that great engine of reason and reform, moved across borders faster than ships. It spoke of liberty, justice, and human rights. It questioned tradition, religion, and authority. It gave birth to the notion that nations were not the property of kings but of people, that governance could be chosen, and that laws should serve the many rather than the few.

These ideas were not always welcomed. They were suppressed, censored, and feared. But they endured. And as they moved through letters, books, and revolution, they remade the world.

The First Stones of the Modern Age

I did not live to see the full unfolding of this transformation, but I knew it had begun. The world of nations, where citizens have rights, governments are accountable, and laws are made by elected voices—that world was not yet fully formed, but it was no longer a dream. We had taken the first steps. We had shown that it could be done.

From North America to France, from the Caribbean to India, from the salons of Europe to the ships at sea, the old world had cracked. The age of empires was beginning to give way to the age of nations. And though conflict would follow, so too would hope.

Let future generations remember that power does not reside in crowns or castles. It resides in people—in their minds, their choices, and their will to shape the world they inherit. We merely lit the torch. It is theirs to carry forward.

Comments