16. Heroes and Villains of the Age of Exploration: The Journeys of Sir Walter Raleign

- Historical Conquest Team

- Aug 21

- 29 min read

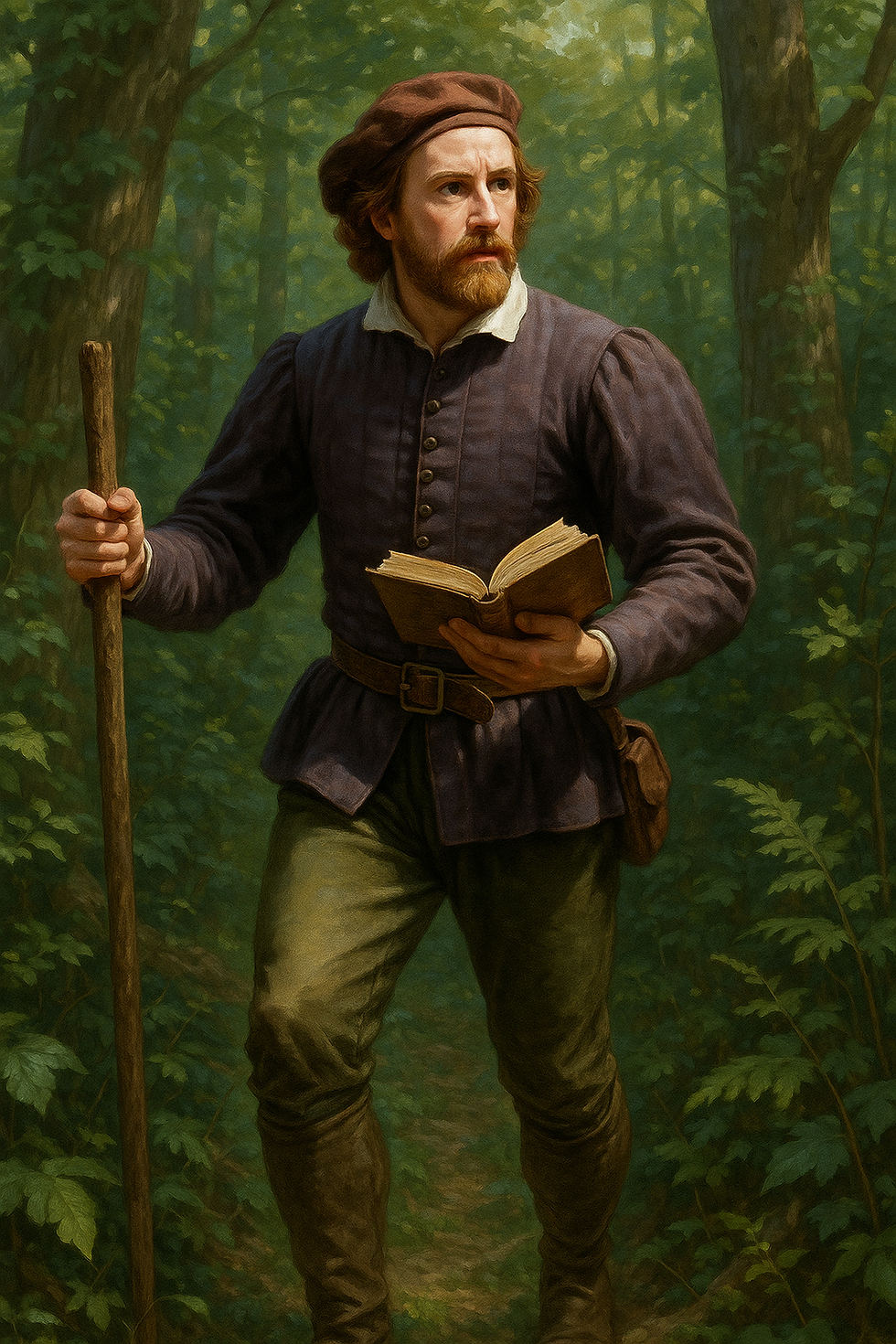

My Name is Sir Walter Raleigh: Courtier, Explorer, and Dreamer of Empires

I was born in Devon in 1552, into a world where England was still finding its footing among the great powers of Europe. My youth was spent in study and adventure, and from the beginning I longed for both knowledge and the thrill of discovery. The seas and distant lands called to me, and I resolved that my life would be shaped by them.

Rising at Court

Fortune came when I won the favor of Queen Elizabeth I. My wit, my words, and my loyalty brought me close to her side. I was granted lands, titles, and privileges, and I became one of her trusted courtiers. Yet court life was a game of power as dangerous as any battle at sea, and I learned to balance ambition with caution, though not always wisely.

Dreams of the New World

I longed to make England strong across the seas, to rival mighty Spain. With the queen’s blessing, I organized voyages to the Americas. It was I who gave the name Virginia to honor Elizabeth, the Virgin Queen. My dream was not just gold or glory, but colonies that would root England in the New World, forever changing the destiny of my homeland.

The Roanoke Venture

My greatest hope was Roanoke, the first English colony in North America. Brave men and women crossed the ocean, carrying my vision. Yet their fate became a mystery. When ships returned, the settlers had vanished, leaving behind only the word “CROATOAN” carved into a post. The world still calls it the Lost Colony. Though the failure haunted me, it did not end my belief in England’s destiny overseas.

My Poetic Soul

Many know me as an explorer and courtier, but I was also a man of letters. I wrote poems of love, ambition, and despair, and accounts of my journeys. For me, words were as mighty as swords, able to preserve the spirit of an age and win favor in the eyes of kings and queens.

Imprisonment and Fall

The death of Queen Elizabeth and the rise of King James I brought a sharp turn in my fortune. I was accused of treason, imprisoned in the Tower of London, and stripped of my titles. Years later, desperate for redemption, I led an expedition to Guiana in search of gold. It ended in disaster and the death of my son. My enemies at court pressed for my downfall, and the king condemned me.

My Final Days

In 1618, I faced the executioner’s block. I met death with the courage of a soldier and the calm of a man who had long known ambition’s cost. I left behind a name tied to dreams of empire, voyages across unknown seas, and a cautionary tale of power’s rise and fall. My life was a tapestry of triumphs and tragedies, woven into England’s march toward a new world.

My Rise at Court

I was born a gentleman of Devon, but my beginnings were far from grand. Through wit, service, and unshaken loyalty, I earned the notice of Queen Elizabeth. I stood tall, spoke boldly, and offered her my devotion, for I knew that in her favor lay the key to power. She made me a knight, gave me lands, and trusted me with her confidence. In those halls of glittering ambition, every gesture mattered. To rise was to balance charm with courage, and I played the game with all my skill.

The Rivalry with Spain

Yet my thoughts were not confined to courtly intrigues. Beyond the palace walls stretched a greater struggle, one that consumed the seas and the souls of nations. Spain had become the giant of Europe, rich with the gold and silver of the New World. Their galleons brought wealth beyond measure, and with it, power enough to threaten all Christendom. I longed to see England stand as their equal, not cower in their shadow. To rival Spain was not merely my desire—it was a necessity for my country’s survival.

Ambition and Empire

It was ambition that burned within me, a fire I could not quench. Yet my ambition was never mine alone. I believed that by seeking fortune across the seas, I also sought glory for England. Colonies, trade, and discovery would enrich the crown, strengthen her navy, and give her people a place among the mighty. My name and my nation’s power were bound together. To fall short was to shame myself and weaken England. To succeed was to carve both into the annals of history.

The Call of the Ocean

Thus I turned my gaze westward, across the unending ocean. There lay both danger and promise—lands untamed, peoples unknown, and riches yet to be claimed. For me, the sea was not simply water but a road to greatness. It was the path that joined my own fortune with the destiny of England. Ambition, court, and empire were threads of the same cloth, and I wove them together in the hope of building a new world.

The Ambitions of Exploration and Court Life – Sir Walter Raleigh

I was born a gentleman of Devon, but my beginnings were far from grand. Through wit, service, and unshaken loyalty, I earned the notice of Queen Elizabeth. I stood tall, spoke boldly, and offered her my devotion, for I knew that in her favor lay the key to power. She made me a knight, gave me lands, and trusted me with her confidence. In those halls of glittering ambition, every gesture mattered. To rise was to balance charm with courage, and I played the game with all my skill.

The Rivalry with Spain

Yet my thoughts were not confined to courtly intrigues. Beyond the palace walls stretched a greater struggle, one that consumed the seas and the souls of nations. Spain had become the giant of Europe, rich with the gold and silver of the New World. Their galleons brought wealth beyond measure, and with it, power enough to threaten all Christendom. I longed to see England stand as their equal, not cower in their shadow. To rival Spain was not merely my desire—it was a necessity for my country’s survival.

Ambition and Empire

It was ambition that burned within me, a fire I could not quench. Yet my ambition was never mine alone. I believed that by seeking fortune across the seas, I also sought glory for England. Colonies, trade, and discovery would enrich the crown, strengthen her navy, and give her people a place among the mighty. My name and my nation’s power were bound together. To fall short was to shame myself and weaken England. To succeed was to carve both into the annals of history.

The Call of the Ocean

Thus I turned my gaze westward, across the unending ocean. There lay both danger and promise—lands untamed, peoples unknown, and riches yet to be claimed. For me, the sea was not simply water but a road to greatness. It was the path that joined my own fortune with the destiny of England. Ambition, court, and empire were threads of the same cloth, and I wove them together in the hope of building a new world.

The Vision of Colonization in the New World – Told by Sir Walter Raleigh

From the moment I won the queen’s favor, I dreamed not only of voyages but of planting England’s roots in distant soil. Spain had its mighty empire in the Americas, but I believed England, too, could claim her place. A colony across the sea would not only enrich us with trade and resources but would also spread our faith and culture. It was more than ambition—it was destiny. I saw the New World as the stage on which England’s future greatness would be written.

The Birth of Virginia

When I was granted a patent to explore and colonize, I chose to honor Elizabeth by naming the land Virginia, after the Virgin Queen herself. The name carried with it a sense of purity, promise, and new beginnings. I imagined towns filled with English families, fields of crops to sustain them, and harbors from which our ships could challenge Spain’s dominance. Virginia was not just a place on a map—it was the vision of a nation unchained from dependence on others.

The Roanoke Experiment

To bring this dream to life, I sent men, women, and children to settle on Roanoke Island. They carried with them the hope of a permanent English home across the ocean. The land was fertile, the waters abundant, and the possibilities endless. Yet I knew the challenges would be great—distance, supply, and the delicate balance with the native peoples. Still, I believed that the hardships would be worth the reward, for every nation that sought greatness had once endured the trials of foundation.

A Dream Beyond My Lifetime

Though Roanoke would become known for its mystery and failure, I never abandoned the vision. I knew that even if my efforts faltered, the idea of colonization would outlive me. In time, others would take up the task, and England would plant her flag across vast continents. My dream was not for myself alone but for the generations to come, who would one day call that land their home. Colonies, I believed, were the key to empire, and empire the key to immortality.

My Name is Richard Grenville: Soldier, Sailor, and Servant of England

I was born in 1542 in Devon, into a proud and restless family that had long served the crown. From a young age I was trained in the arts of war, for England was always threatened by enemies abroad. My youth was marked by discipline and ambition, and I sought glory wherever it might be found—on the battlefield or upon the seas.

A Life of Soldiering

Before I became known upon the oceans, I fought as a soldier in Hungary against the Ottoman Turks. I learned the ways of battle, the hardship of campaigns, and the honor that came with serving Christendom. War sharpened my courage and taught me that loyalty and resolve mattered more than life itself.

Service to England

Upon returning to my homeland, I gave my service to England and her queen. The seas had become the battlefield of empires, and Spain ruled the waves with her mighty treasure fleets. I joined with my cousin, Sir Walter Raleigh, in daring enterprises across the Atlantic. Together we dreamed of colonies, wealth, and power that could rival Spain’s.

The Roanoke Venture

In 1585 I sailed to the New World, commanding the fleet that carried Raleigh’s settlers to Roanoke. I saw with my own eyes the dangers and promises of those distant lands—strange peoples, unfamiliar climates, and endless uncertainty. Though the venture faltered, it was a bold step, and I was proud to be part of it.

The Call of the Sea

More than once I crossed swords with the Spanish upon the waters. I believed every Englishman must stand firm against them, for Spain sought to crush our nation’s spirit. To me, the sea was both battlefield and destiny, and I was never far from it.

The Battle of Flores

My final and greatest moment came in 1591. Off the Azores, my ship, the Revenge, was caught alone against a fleet of fifty Spanish vessels. I chose to fight rather than flee. Through the night and into the next day, my crew and I battled until we could fight no more. Though outnumbered beyond reason, we sank many of their ships and bloodied their pride. At last, wounded and weary, I was taken prisoner, but I did not regret the stand we made.

My Death and Legacy

I died soon after the battle, but my name lived on. The story of the Revenge spread across Europe, a tale of courage against overwhelming odds. I wanted England to know that a single ship, with men of iron hearts, could stand against an empire. That was my life, and that was my lesson: to fight with honor, even when victory is beyond reach.

Naval Expeditions and the Struggle Against Spain – Told by Richard Grenville

From the moment I first set sail across the Atlantic, I knew the ocean was both friend and foe. Its storms struck without warning, tearing sails and splintering masts, while its vast emptiness tested the spirit of even the bravest crew. Yet the dangers of the sea were not only of wind and wave. Spanish ships patrolled the waters like wolves, their galleons heavy with treasure from the Indies. To sail against them was to invite battle, and I welcomed it.

Piracy and Power

In those days, England and Spain were locked in a struggle not just for land but for wealth and dominion. Their treasure fleets carried silver and gold beyond imagination, plundered from the New World. To strike them was to weaken an empire, and so our ships became hunters. Some called it piracy, but I called it service to queen and country. Every Spanish vessel we captured was a victory for England, every coin a blow against our enemy’s might.

The Pride of the Revenge

Of all the ships I commanded, none is remembered like the Revenge. She was my sword upon the waters, swift and unyielding. In 1591, off the Azores, I faced my greatest trial. Alone and outnumbered, with barely two hundred men, we found ourselves against a fleet of fifty Spanish ships. My officers urged retreat, but I would not run. To yield the ocean without a fight was unthinkable. I resolved to stand, though the odds defied reason.

The Last Stand

For fifteen hours we battled. The Revenge was surrounded, torn by cannon fire, and yet she fought on. My men fell one by one, but their courage did not falter. We sank ships, crippled others, and struck fear into the hearts of the Spanish. At last, wounded and bleeding, I was taken prisoner. The Revenge herself was lost, but her spirit burned brighter in death than in life.

A Legacy of Defiance

I did not live long after that battle, but my stand against Spain became legend. The story spread across Europe, a testament to English valor and resolve. I wanted the world to know that one ship, well manned and fiercely fought, could shake an empire. That was the struggle of my life—the defense of England’s honor upon the seas, against storms, against enemies, and against the shadow of Spain’s power.

My Name is Thomas Hariot: Mathematician, Scientist, and Observer of New Worlds

I was born in 1560, a time when England hungered for knowledge and exploration. From my youth, I was drawn to numbers, patterns, and the mysteries of the heavens. At Oxford I studied mathematics, a discipline that sharpened my mind and gave me the tools to understand the order of creation. Knowledge became my compass, and it guided the course of my life.

In Service to Sir Walter Raleigh

My talents brought me into the circle of Sir Walter Raleigh, whose grand vision of empire in the New World required not only courage but also science. I became his advisor and tutor, teaching navigators the mathematics of sailing and the art of charting unknown seas. Raleigh’s patronage gave me the chance to put my learning into practice on ventures that carried England’s hopes across the Atlantic.

Journey to Roanoke

In 1585, I sailed with Raleigh’s expedition to Roanoke. I was no soldier, but an observer, eager to record the land and its people. I studied the soil and found it fertile, the rivers full of fish, and the forests rich with game. I believed that this place, if carefully tended, could sustain an English colony. My writings would later become a window into this fragile experiment of settlement.

Learning from the Algonquians

Among the greatest of my experiences was living among the Algonquian peoples. With patience and respect, I began to learn their words, customs, and ways of life. Their knowledge of the land was profound, their agriculture skillful, and their society complex. I recorded their language, for I knew that mutual understanding was the first step toward peace. Yet I also saw the tensions that grew between our peoples, born of mistrust and misunderstanding.

Man of Science

I was not only a traveler but a seeker of truth in every realm of nature. I experimented with optics, studied the stars, and made observations that later prepared the way for the discoveries of others. Long before Galileo raised his telescope, I turned mine skyward and saw the moon in greater detail than ever before. Science was my true voyage, and I sailed it until the end of my life.

Later Years and Legacy

Though I did not lead great armies or command mighty ships, my contribution was of a quieter sort. I gave knowledge where there was ignorance, records where there was silence, and clarity where there was confusion. When I died in 1621, I left behind maps, observations, and writings that captured a moment when England first stretched its hand across the ocean. My life was proof that empire is built not only by the sword, but also by the mind.

Life in the Early Colonies – Told by Thomas Hariot

First Impressions of Roanoke

When I first stepped onto the shores of Roanoke in 1585, I saw a land filled with both promise and challenge. The island was fertile, the rivers alive with fish, and the forests rich with game. To my eyes, it seemed a place where English settlers could thrive, if only they learned to live as the people of the land had done for generations.

Food and Agriculture

The Algonquian peoples taught us much about sustenance. They grew maize, beans, and squash, crops that could flourish in soil unfamiliar to us. They showed us how to plant fish with corn to strengthen the earth, and how to dry and preserve food for the colder months. I recorded these practices carefully, believing they could ensure survival for future colonies. Our settlers brought their own seeds from England, but many did not take to the new climate, making the native crops all the more essential.

Houses and Shelter

The English built their houses in ways they had known at home, with timber frames and thatched roofs, but these often proved less suited to the environment. The Algonquians’ houses, built of saplings bent into domes and covered with bark or mats, were warm in winter and cool in summer. I noted their efficiency, for adaptation to the land was as important as courage on the sea.

Struggles of Survival

Despite the abundance I saw, the settlers often struggled. Supplies from England were uncertain, storms delayed ships, and not all the men were skilled in farming or hunting. Some quarreled among themselves, others grew desperate. The lessons of the land were clear, but pride sometimes blinded us from learning. I observed with care, hoping my records might guide those who came after, so that failure need not be repeated.

A Scientist’s Hope

As I studied, I believed that knowledge was our greatest tool. If England could learn to live from the land rather than against it, the colonies could prosper. At Roanoke, I wrote not just of the hardships, but of the possibilities—a place where English families might one day build lasting homes, sustained by the wisdom of those who had lived there long before us.

Science, Mapping, and Language Study – Told by Thomas Hariot

When I lived among the Algonquian peoples of Roanoke, I devoted myself to learning their words. At first, communication was slow, built on gestures and repeated sounds, but over time I gathered lists of their terms for food, tools, and places. Their language opened a window into their lives, and I found it both rich and precise. By recording it, I hoped not only to ease understanding between our peoples but also to provide future settlers with the means to speak rather than fight.

Recording the Natural World

The land was filled with plants and animals unknown to England, and I saw it as my duty to document them. I noted the fruits that could be eaten, the roots that could be boiled, and the herbs used by the natives for healing. I described the fish, the birds, and the creatures of the forests, believing that knowledge of these things might help England thrive in this strange environment. To me, each discovery was both a matter of survival and a contribution to the growing body of natural philosophy.

The Art of Mapping

I also set about the work of mapping the land and waters. With compass and careful observation, I traced the shapes of rivers, the outline of the coast, and the locations of villages. To chart a new land was more than an act of science—it was an act of power, for maps guided ships, claimed territories, and gave order to the unknown. My maps and notes would later serve others who sought to follow where we had gone.

Science in Service of Empire

Though my curiosity was genuine, I also knew that my work had greater purpose. Every word written, every plant described, every line drawn on a chart became part of England’s claim to the New World. Science was not separate from empire—it was its servant. I believed that by recording these truths, I was laying a foundation for England’s future, so that those who came after us would be wiser, better prepared, and more enduring.

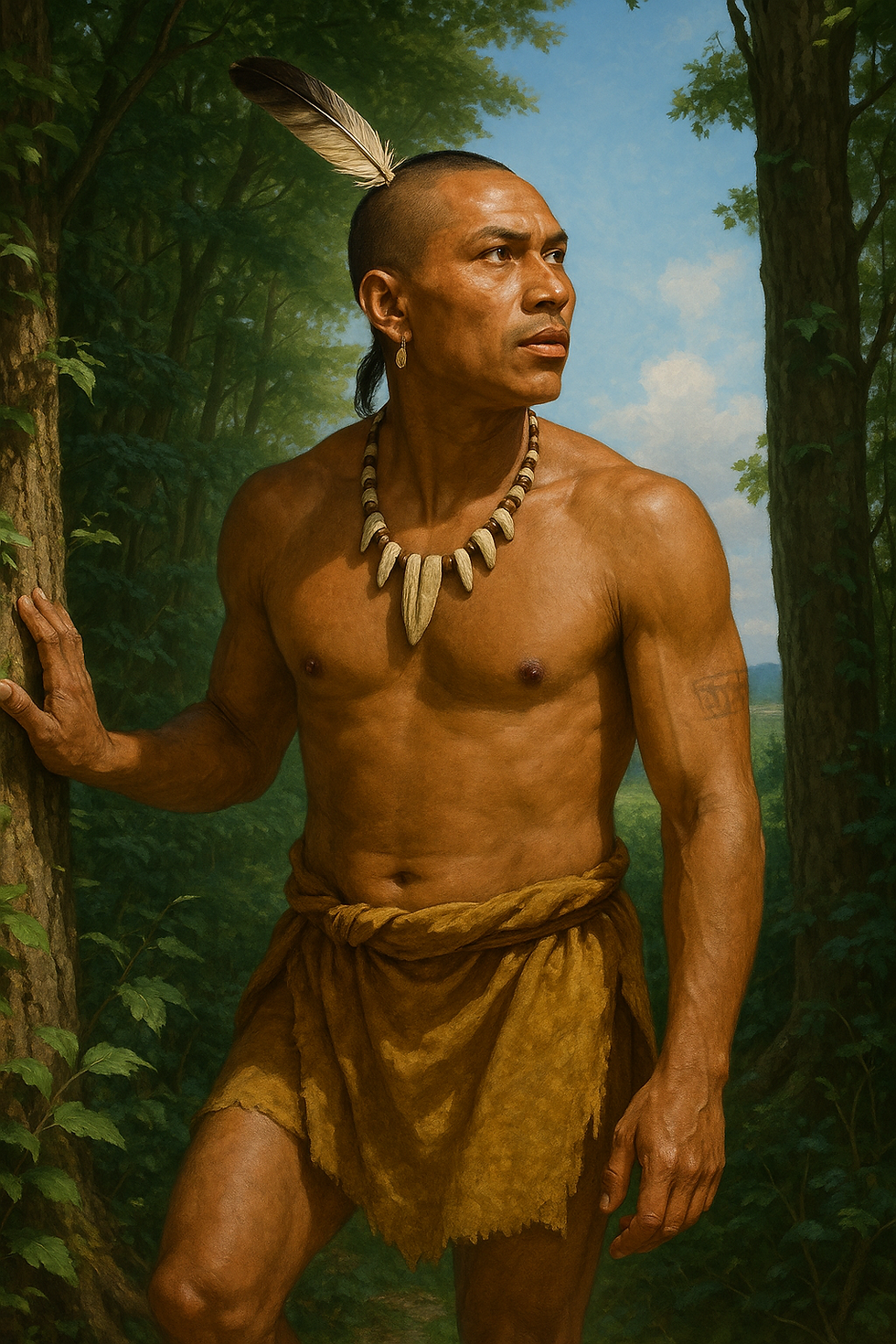

My Name is Manteo: Croatan Leader and Bridge Between Two Worlds

I was born among the Croatan people, who lived along the Outer Banks of what you now call North Carolina. The land and sea were our life. We fished the waters, hunted the forests, and planted our corn and beans in the soil that had sustained our ancestors for generations. Our world was complete, yet it was also fragile, for neighboring tribes often warred with us, and survival demanded both strength and wisdom.

First Encounters with the English

When the English first came to our shores, we did not know if they were spirits or men. Their ships were vast, their weapons thundered, and their hunger for land and power was plain. Yet they also sought friendship, and I, as a leader among my people, chose to guide them. I believed peace might bring strength against our rivals and open new paths for my people’s future.

Journey Across the Sea

I traveled with the English across the great ocean to their homeland. The voyage was long and perilous, but I was curious to see this world from which they came. In England I was received with wonder, clothed as they clothed themselves, and even baptized into their faith. They gave me the title of Lord of Roanoke, but I never forgot that I was first a Croatan. I tried to understand them so that I might protect my people.

The Roanoke Settlers

When I returned to my homeland, I stood between the English and the Algonquians. I spoke their words and sought to ease mistrust. I guided the settlers of Roanoke and urged peace, but suspicion and conflict grew. Misunderstandings turned to anger, and anger to bloodshed. I watched as friendship gave way to fear, and I knew that my role as a bridge was both vital and dangerous.

Between Two Worlds

I lived in two worlds yet belonged fully to neither. To my people I was a leader touched by foreign ways. To the English I was a noble ally but never their equal. Still, I believed that our survival depended on finding a path of peace, even as storms of war gathered. My life was spent trying to keep that fragile balance.

My Legacy

I died around 1590, as the fate of the Roanoke settlers remained a mystery. Some remember me as the first Native to be called a lord in the English world. Others recall me as the interpreter who carried words across the divide. But I hope I am remembered as a man who sought to hold two peoples together, even as the tide of history pulled them apart. My life was a story of meeting worlds, of promises and betrayals, and of the hope that peace might yet be found.

The Role of Native Allies and Guides – Told by Manteo

I still remember the first time the English ships came to our shores. They were like floating islands, larger than any canoe we had ever known, and the men upon them carried weapons that roared like thunder. Many of my people feared them, for we did not know if they were spirits or men. Yet I looked beyond fear and wondered what might be gained from knowing them.

Building Alliances

When the English came to Roanoke, I chose to guide them. I spoke with their leaders and offered them food and shelter. I believed friendship with them could give my people strength against our rivals. In return, they gave us metal tools, beads, and cloth, items we had never seen before. I became their ally, a bridge between their world and mine, for I could walk in both and carry words across the divide.

The Work of a Guide

I showed them the rivers where fish ran thick, the fields where corn grew tall, and the paths through the forests. Without this knowledge, their survival would have been far more difficult. I served as interpreter, carrying their strange words to my people and carrying ours back to them. It was not easy, for meaning often slipped between us, but I tried to make peace where suspicion lingered.

Misunderstandings and Tensions

Yet even with friendship, mistrust grew. The English often misunderstood our ways, and some of my people grew angry at their demands. Small disputes became large, and fear sometimes turned allies into enemies. I stood between them, hoping to heal the divide, but I learned how fragile peace can be when two peoples do not truly understand one another.

My Role in the Balance

I became a symbol of alliance, named Lord of Roanoke by the English, yet I was always Croatan in my heart. I wished for my people to thrive, and I hoped the strangers would live in harmony with us. But I saw clearly that their hunger for land and power could not be easily bound. My role as guide was not only to lead them through our forests, but also to try to lead them toward peace—a path far more difficult to follow.

Cultural Exchange and Misunderstanding – Told by Manteo

When the English first came among us, we watched them with wonder. Their ships were larger than any we had imagined, and their weapons struck fear with fire and thunder. Some of my people thought them powerful spirits, while others believed they were only men with strange tools. We welcomed them as guests, for in our way of life, strangers were to be shown respect. Yet their customs were unlike ours, and soon we saw that they did not always understand the meaning of our gifts or the ways of our villages.

How They Saw Us

To the English, we were both allies and curiosities. They marveled at our crops, our canoes, and our hunting skills, yet they also looked upon us as if we were children in need of guidance. Some spoke of teaching us their faith and ways of living, as though our own ways were not enough. They often misread our hospitality as weakness, and they believed that what was shared once could always be taken.

The Strains of Misunderstanding

At times, what began as friendship soured quickly. A gift of food was sometimes seen by the English as tribute, when to us it was generosity. When they took more than was given, my people grew angry. When they demanded obedience, they did not see that each village held its own leaders, and no man could command all. Misunderstandings grew into quarrels, and quarrels into bloodshed.

The Fragile Balance

I stood between the two worlds, speaking their words to my people and ours to them. I tried to explain that their hunger for land and wealth was not the same as our desire for harmony with the land. Yet the gulf between our ways was wide. They saw power in ownership, while we saw strength in sharing. They saw wealth in gold and silver, while we valued corn, fish, and peace.

Lessons of a Broken Exchange

In the end, I learned that cultural exchange can bring knowledge, but also conflict if not tempered with respect. The English and my people saw each other through eyes clouded by fear, pride, and misunderstanding. We might have built a lasting bond, but instead, suspicion weakened the friendship we had begun. I, who wished to bridge two worlds, saw how easily that bridge could crumble when neither side truly understood the heart of the other.

The Mystery of the Lost Colony – Told by Sir Walter Raleigh

When I first sent men, women, and children to Roanoke, I believed they would be the roots of England’s new world. They carried with them not only provisions and tools, but also the promise of permanence—English homes, English families, English life across the ocean. It was a daring step, for never before had our people planted themselves so far from home. I dreamed that one day they would grow into towns and cities, standing as proof of England’s strength.

The Silence of Absence

But when ships returned after years of absence, the settlement lay empty. Houses were deserted, fields overgrown, and no voices welcomed the English back. The only sign left behind was a single word carved into a post—“CROATOAN.” It offered a clue, yet no certainty. Had the settlers gone willingly to live with friendly tribes? Had they perished from hunger, disease, or war? The truth was swallowed by the land, leaving only silence in its place.

A Stain on My Name

The mystery of Roanoke clung to me like a shadow. Some blamed me for sending the settlers too soon, with too few supplies. Others whispered that I had chased glory rather than cared for those I placed across the sea. Though I sought to defend my vision, I could not escape the judgment of those who saw only failure. The Lost Colony became a wound to my reputation, one that never fully healed.

England’s Haunted Ambition

Yet it was not only my name that bore the weight of the loss. England, too, was shaken. Doubt spread over whether we were ready for such ventures. Some questioned if our people could truly survive in the New World, or if Spain’s dominance there was unbreakable. The disappearance of the colonists became more than a mystery—it was a warning that empire came at a cost, and that dreams of greatness could easily turn to ruin.

The Unanswered Question

To this day, I do not know their fate. Were they taken in by allies and lived on in other villages? Or did they fall to hunger and despair? The question haunts me, for in their story lies both the hope and peril of exploration. The Lost Colony is remembered as England’s first attempt, and its first failure, a reminder that ambition can open the door to glory, but also to tragedy.

The Clash of Empires in the Atlantic World – Told by Richard Grenville

In my time, the Atlantic was more than an ocean. It was the battlefield upon which empires fought for power. Spain, swollen with the gold and silver of the Indies, claimed the seas as their own. Their galleons carried treasure beyond imagining, and with it they purchased armies and built a vast empire that stretched across the world. England, smaller but proud, could not hope to stand idle while Spain’s shadow grew ever darker.

England’s Answer

Men like Sir Walter Raleigh looked to the New World as the key to England’s future. Colonies would not only provide wealth but also secure our place among the nations. Each settlement was a strike against Spain’s monopoly, each ship a challenge to their claim. To plant English roots in America was as much an act of war as it was of discovery. I knew well that every voyage we undertook was not just for trade or knowledge, but to defy the might of Spain.

Privateers and Pirates

Our struggle was fought in more ways than one. We Englishmen turned the sea into our battlefield, harrying Spain’s treasure fleets. Some called us privateers, others called us pirates, but we knew the truth—we were warriors in a war without formal declaration. Every Spanish ship we captured was a victory for England, a blow against their wealth and their pride. The Atlantic became a chessboard of ambushes and running battles, with each side vying for mastery.

Colonization as Strategy

The colonies Raleigh envisioned were more than dreams of settlement; they were fortresses in disguise. An English foothold in the New World meant harbors for our ships, outposts against Spanish fleets, and places from which we could strike at their empire. Colonization and war were bound together, each feeding the other. To settle the New World was to wage war upon Spain with roots instead of cannon fire.

The Wider War

What began on the seas stretched into a struggle that encompassed nations. The clash of empires in the Atlantic was but one theater in a greater conflict, where Protestant England and Catholic Spain fought for supremacy in Europe and beyond. I believed then, and still do, that Raleigh’s ventures were part of that vast struggle. His colonies, my battles, our raids—they were all threads in the same tapestry of war, one that shaped the destiny of nations.

The Fall of Raleigh: Ambition and Downfall – Sir Walter Raleigh

With the death of Queen Elizabeth, my fortune faded. She had been my shield, my patron, and my constant support. When King James took the throne, I found myself a stranger in the court I once commanded. Old rivals whispered against me, and soon I was accused of treason in a plot I did not weave. Though the charges were doubtful, I was condemned and cast into the Tower of London. There I lingered for years, a prisoner whose dreams of empire turned to dust within stone walls.

The Final Expedition

At last, freedom was offered to me, but with it came a heavy burden. I was to lead an expedition to Guiana in search of a golden city, a prize that might restore my name and enrich the crown. I accepted, for what choice did I have? I longed to prove myself once more, yet the venture was doomed from the start. The land was harsh, the gold a phantom, and in the attempt I lost my eldest son. His death struck me harder than any wound I had known, for he had shared my ambition and paid the price of it.

Betrayal and Condemnation

The expedition brought not glory but ruin. My men, desperate and broken, struck at a Spanish outpost, though I had sworn to King James that peace would not be violated. Spain demanded satisfaction, and my enemies at court seized their chance. I was brought back in chains, betrayed by circumstance and condemned by politics. My life was no longer my own but a token to be spent in the games of kings.

Facing the Block

In 1618, I was led to the scaffold. I met my fate with calm, for I had long known that ambition carries its price. I declared to those gathered that I died a true servant of England. The axe fell, and with it ended the life of a man who had reached for the world and grasped only shadows.

Lessons of My Fall

From my story, let this be learned: ambition can raise a man high, but it can also cast him low. Exploration and empire bring glory, yet they are bound to risk, to politics, and to the shifting winds of favor. I dreamed of planting England across the seas, and though I did not live to see it fulfilled, others carried the vision forward. My downfall was my own, but the dream endured.

The Role of Religion in Exploration – Told by Thomas Hariot

In my age, religion was bound tightly to the cause of exploration. To many in England, the voyages across the Atlantic were not only for wealth and discovery but also to carry the Protestant faith into distant lands. Spain, our great rival, sailed under the banner of Catholicism, spreading its priests and doctrines wherever its soldiers went. To counter them, our colonization was seen as a mission not just of empire but of faith, to uphold Protestant strength against Catholic power.

The Desire to Convert

Among the plans for Virginia and Roanoke was the hope that the native peoples might embrace Christianity. Some of my companions spoke with zeal of turning them from what they called heathen ways. They believed that to spread the Gospel was as important as planting corn or building forts. For the queen and many of her counselors, such conversions would prove the righteousness of our cause, showing that England’s ventures were guided by God’s hand.

Observing Algonquian Beliefs

Yet when I lived among the Algonquian peoples, I saw a different truth. Their faith was not void or empty but rich with meaning. They spoke of spirits that dwelled in rivers, forests, and skies. They honored their deities with song, dance, and offerings, believing that harmony with the natural world was a sacred duty. I studied their ceremonies and their words, and though I did not share their beliefs, I saw in them the same desire to explain the mysteries of life that we carried in our own churches.

Misunderstandings and Judgment

The English often failed to see this depth. To them, the Algonquian practices were strange or false, and some mocked them as the works of the devil. Such judgments bred contempt rather than understanding, making true fellowship difficult. I tried in my writings to describe their religion with fairness, though I knew that many in England would read my words only as a call to convert and conquer.

Religion as a Weapon

In the end, religion served as both compass and weapon in our endeavors. It gave moral justification to the risks of colonization and framed the struggle against Spain as holy war. But it also blinded many to the humanity of those we encountered. To me, the role of religion in exploration revealed both our highest hopes and our gravest failings, for it could inspire peace, yet more often it fueled division.

Violence and Atrocity in Contact Zones – Told by Richard Grenville

When we English came to the shores of the New World, we brought with us not only hope but also fear and steel. The meeting of peoples was rarely peaceful, for mistrust lay on both sides. Our men, hardened by war in Europe, were quick to see danger in every shadow. The natives, proud of their lands, saw us as intruders. Suspicion turned to quarrel, and quarrel to bloodshed, often before peace had any chance to take root.

Raids and Reprisals

I myself led men at Roanoke in 1585. When provisions grew scarce and tempers flared, small disputes with the local villages became larger. A stolen tool, a slighted gesture, or a refusal to trade could spark a skirmish. In one such moment, I ordered a reprisal against a village we believed hostile. Houses were burned, and innocents likely suffered. To some, it was justice; to me, it was necessity in a land where weakness invited ruin. But I knew, even then, that such acts planted seeds of hatred that could not be easily pulled out.

The Weight of Violence

These were not isolated moments. Across the seas, Spaniards, Frenchmen, and English alike carved their claims with the sword. At times, settlers faced ambushes and retaliated with fire and shot. At others, soldiers destroyed whole villages in the belief that fear would secure obedience. The wilderness was not empty—it was home to people who would not yield it easily. And so violence became the language of empire, spoken as often as treaties or promises.

Atrocity and Empire

Some called it cruelty, others called it strength, but I will not hide it: colonization was rarely gentle. Where diplomacy failed, we forced our will. Where suspicion lingered, we struck first. I do not say this with pride, but with truth. Men who seek to plant a nation in another’s soil must reckon with the cost, and the cost is often paid in blood.

A Soldier’s Reckoning

Looking back, I see that violence was both our weapon and our weakness. It secured us land in the short term, but it destroyed trust that might have led to lasting friendship. The New World could have been a place of alliance and shared strength, but too often we made it a battlefield. Such was the brutal reality of empire-building, and I, as a soldier, played my part in it.

Propaganda and the Selling of Colonies – Told by Thomas Hariot

When Raleigh and others sought to build colonies in the New World, they needed more than ships and sailors. They needed money, men, and the confidence of those at court. Exploration was costly, and investors demanded hope of profit. It fell to men like me to provide that hope, not only through maps and charts but through words that would stir imagination. My writings were read not only as records of discovery but also as promises of plenty.

The Glowing Reports

In my account of Virginia, I spoke of fertile soil, abundant game, and rivers alive with fish. I wrote of fruits, trees, and crops that seemed to grow without end. I described a land where settlers could prosper, where families could build a new England in America. My words painted the picture of a paradise, one that would reward courage and labor with wealth and comfort. These descriptions were true in part, yet they were chosen with care to strengthen the cause.

Downplaying the Hardships

I did not speak as often of the hunger that came when supplies ran low, or of the storms that battered our ships, or of the mistrust that grew between our people and the natives. I feared that such truths would weaken support for future voyages. Investors wanted certainty, not doubts, and settlers needed encouragement, not despair. Thus the dangers were softened, and the hardships left in shadow.

The Role of Propaganda

In this way, our writings became more than reports—they became instruments of persuasion. They were used to attract money, settlers, and the approval of the queen. We told stories that elevated the vision of empire and muted its risks. This was propaganda, though we did not call it so. It was the selling of a dream, and I was one of its craftsmen.

The Consequences of Persuasion

Looking back, I see how our glowing words raised expectations that reality could not match. Some who came seeking ease found only toil and despair. Yet without such words, the colonies may never have been attempted at all. The dream of empire required more than courage; it required belief. And belief, I confess, was built as much upon hopeful description as upon sober truth.

The Spanish Black Legend – Told by Richard Grenville

From the first days we ventured westward, stories spread across Europe of Spain’s deeds in the New World. Priests and travelers told of native peoples enslaved, villages burned, and cruelty without mercy. The Spanish, it was said, sought gold with such hunger that they trampled every soul in their path. These tales became known among us as the Black Legend, a portrait of Spain painted in blood and fire.

England’s Use of the Legend

We Englishmen seized upon these stories, for they served our cause well. If Spain’s empire was built on cruelty, then ours would be painted as just. We told ourselves and others that our colonies would not enslave but uplift, that we came not only to claim land but to spread the light of Protestant faith. The Black Legend gave us a moral weapon, a reason to strike at Spain and to defend our own ambitions before the world.

The Question of Superiority

Yet I must confess, the matter was never so simple. I saw with my own eyes how violence marked our own ventures. We raided villages when supplies were scarce, burned homes to teach lessons, and shed blood in the name of survival. Were we always more merciful than Spain? I cannot say it with certainty. Men in strange lands, pressed by hunger and fear, are quick to wield the sword, whether Spanish or English.

Truth and Convenience

The Black Legend was not without truth, but it was also convenient. It allowed us to see ourselves as righteous even when our hands were stained with the same sins. It gave us the cloak of morality, even as we fought for power, treasure, and empire no less fiercely than our rivals. In war, tales often serve as weapons, and this tale was one of our strongest.

A Soldier’s Reflection

As a man of arms, I fought Spain without hesitation, for they were the great threat to England. But in honesty, I cannot claim that our way was always pure. The Spanish Black Legend made it easier for us to believe in our cause, but history will judge whether we were as different from Spain as we claimed. In the end, empire is not built by legends, but by deeds, and deeds are often harsher than the stories told to justify them.

Comments