11. Heroes and Villains of the Industrial Revolution - The Oil Wars

- Historical Conquest Team

- Jul 26, 2025

- 38 min read

My Name is Mary Starbuck: The “Great Woman” of Nantucket Whaling and Oil

My name is Mary Starbuck, and I was born Mary Coffin in 1645, on the island of Nantucket—though it was not yet the busy port or whaling town you may know it as today. My parents were among the first English settlers on the island, and I grew up surrounded by wild landscapes, hard work, and the promise of a new life. Life in those early days was not easy. We cleared the land ourselves, traded with the native Wampanoag people, and built homes out of timber we brought by boat. As a girl, I learned quickly how to manage not just a household, but a community.

A Marriage of Strength and Vision

I married Nathaniel Starbuck when I was just a teenager, and together we built one of the most prominent families on the island. Nathaniel was a respected leader and trader, but it was not uncommon for me to take charge of our affairs. While he was at sea or away managing business, I kept the books, negotiated agreements, and ensured the trade of goods continued smoothly. In time, we expanded our home into what became a central meeting place for the community—both for business and for worship. I was not content to remain silent in the background; I believed women had a voice, and I used mine.

The Heart of the Island’s Spiritual Life

As Quakers, our faith did not separate the roles of men and women as strictly as others did in those days. That gave me space to speak openly and spiritually. I became the first Quaker woman minister on Nantucket and preached regularly at our home. People called it the Great Meeting House, though it was just our parlor. Neighbors gathered not just to worship but to listen, to debate, and to plan. I was often asked to interpret the scriptures or to speak on matters of faith. In time, I became known as “the Great Woman,” not for power, but for the way I guided our island in both spirit and society.

Building a Whaling Empire

Though I did not set out in ships myself, I helped lay the foundation for Nantucket’s whaling economy. Our family was involved in early ventures to hunt whales offshore, and I managed the business side of those risky enterprises. I saw how the whale oil we brought in could be sold in Boston and beyond, lighting homes across the colonies. As Nantucket grew, so did the importance of the oil trade. I ensured contracts were honored, captains were paid, and families were supported while their husbands were at sea. In truth, it was often the women who kept Nantucket running while the men chased the whales.

Legacy of a Woman Unafraid to Lead

I lived a long life for my time—into my early seventies—and in that span I witnessed Nantucket rise from a modest island settlement to a thriving trade hub. I raised ten children, many of whom became leaders in business, ministry, and governance. I left behind not just a home or a name, but a way of life. I taught that faith and commerce could live side by side, that women could lead without apology, and that a community is built not just with tools and ships, but with courage and conviction.

A Voice Across Time

If you are reading my story now, long after I’ve passed, I ask that you remember this: there are many kinds of power. Some wield it with weapons, others with wealth. I held it in words, in actions, and in the quiet strength of daily work. Whether you are tending a home, speaking in public, or daring to challenge the order of things—do so with clarity and purpose. The world needs women and men who are not afraid to lead with both heart and mind.

A Beacon Fading at Sea: The Energy Crisis of the Early 1800s – Told by Mary

Though I passed from this world in the year 1717, the legacy of my island and the trade I helped nurture lived on well into the 1800s. By then, the once-thriving business of whaling, which had lit cities and homes across the world, began to flicker like a candle running low on wax. In my day, whale oil was a gift from the sea. We pressed it from the heads of sperm whales and the blubber of right whales, filled barrels, and shipped it to ports far and wide. It burned brighter and cleaner than tallow and was prized across the colonies and in Europe. But in the decades after my death, the hunger for that oil grew into something fierce and unrelenting.

The Great Hunt Expands

By the early 1800s, the near waters were no longer enough. The whales we once hunted off Nantucket’s coast became scarce. Ships had to sail farther—from the icy reaches of the Arctic to the storm-lashed waves of the South Pacific. What once was a two-month voyage became a two-year expedition. Young men vanished into the horizon for years at a time, chasing a dwindling promise. Our island's streets, once rich with the smell of rendered oil, now carried whispers of worry. Fewer barrels returned with each voyage. The cost of outfitting a ship rose, and the risk became unbearable for smaller owners.

The Limits of Nature’s Bounty

We had believed, perhaps foolishly, that the ocean’s bounty was endless. We learned otherwise. Whale populations dropped sharply, and the great beasts—clever and wary—began to change their routes or dive deeper, out of reach. For the first time, there was talk of “overfishing,” though the word had yet to settle into everyday language. There were no laws then to protect the sea. No limits. No thought of tomorrow. We took, and took, and took again. It was only when the returns diminished that we questioned whether the sea could recover.

A Town’s Uneasy Realization

Nantucket and her sister ports grew anxious. Oil merchants worried. Candle-makers fretted. Lamps dimmed earlier in the evening. The great whaling ships, once symbols of strength and pride, came home half full or not at all. The towns that had built their wealth on whale oil began to look for substitutes—coal gas in the cities, and rumors of a strange “rock oil” bubbling from the earth inland. The world was waking to a troubling truth: no light, no power, no wealth lasts forever if you take it faster than it can be renewed.

A Woman’s Warning to the Future

If I could have spoken to the people of the 1800s, I would have told them what we began to learn in my own time—that all resources, no matter how vast they seem, are limited by how we use them. The whale gave us light, but it was never meant to carry the burden of an entire world’s hunger. The desperation to find more whales, to sail deeper and farther, was a cry of a society that had pushed nature to its edge. Remember this: every flame has a cost, and every choice leaves a mark. When you light a lamp, ask yourself not only where the oil came from—but what was lost to bring it to you.

My Name is James Watt: My Early Life and the Spark of Curiosity

I know you heard it all before, but let’s recap my life before I tell you more about the Oil Wars and how I played a part. I was born in Greenock, Scotland, in the year 1736, the son of a shipwright and merchant. My father was a practical man, and I often watched him build ships and instruments in his workshop. My mother was educated and thoughtful, and from both I gained a love of learning. As a boy, I was quiet and often sickly, but I had an eye for detail and a fascination with the workings of things. I remember spending hours dismantling and rebuilding small mechanical toys or instruments, trying to understand their secrets. My teachers found me difficult to manage, but they could not deny my hunger for knowledge.

The Move to Glasgow and My First Encounters with Steam

I traveled to Glasgow in my late teens, hoping to improve my craft. There, I was taken under the wing of Professor Joseph Black, who introduced me to the mysteries of heat and latent energy. These ideas would guide my work for decades to come. Eventually, I was appointed instrument maker at the University of Glasgow. It was in this position, surrounded by scholars and thinkers, that I encountered a broken model of a Newcomen steam engine. It was inefficient and clumsy. I knew it could be better.

Revolutionizing the Steam Engine

The Newcomen engine wasted vast amounts of heat by cooling and reheating the same cylinder. My breakthrough came with the idea of separating the condenser from the cylinder, allowing steam to be condensed in a different chamber. This simple change, completed in 1765, vastly improved the engine’s efficiency. But invention is never easy. I struggled for years to secure the funding and resources to build my design. Eventually, I partnered with the bold and driven Matthew Boulton, and together we formed Boulton & Watt. In 1776, our improved engines began appearing in mines and factories. They didn’t just pump water; they powered machines, drove industry, and changed the world.

Steam Power and the Growth of Industry

As our engines spread across Britain, they helped transform every corner of life. Coal mines became deeper and more productive. Textile mills ran faster and longer. Ironworks grew louder and more efficient. Cities swelled with laborers drawn to the hum of industry. My engines made possible what had once been unimaginable. I did not invent steam power, but I gave it purpose. My innovations helped break the limits of muscle and water, and in doing so, gave rise to the modern industrial world.

Later Years and Lasting Impact

In my later years, I turned to new experiments and inventions, including attempts at copying sculpture and improving chemistry. Though none of these matched the success of my earlier work, I remained curious until the end. I retired a wealthy man, but my greatest pride came from the knowledge that I had helped turn the wheel of human progress. When I passed away in 1819, I could already see how far steam had carried the world—and how much farther it would go.

A Message to the Future

If I may leave a thought to those who study my life, it is this: Innovation does not begin with power—it begins with observation. I was not the strongest or loudest in the room, but I watched carefully. I listened to the hiss of steam, the clang of engines, and the whispers of ideas shared between minds. If you do the same, perhaps you too may catch the spark that changes everything.

The Humble Beginnings Beneath the Earth: Rise of Steam – Told by James

Before steam changed the world above ground, it served first beneath it. When I began my work in the mid-1700s, coal mines across Britain faced a dangerous problem—flooding. Water poured into the deep shafts faster than men could bail it out. Early steam engines, like those of Thomas Newcomen, were used to pump water out of the mines. But they were slow and devoured coal. I studied one such engine and saw that it wasted heat by constantly heating and cooling the same cylinder. It was there that I found my purpose: to make steam more efficient, more powerful, and more useful to the world beyond the mine.

The Separate Condenser and a Giant Awakens

My solution came in the form of a separate condenser. Instead of cooling the main cylinder to condense the steam, I allowed the condensation to occur in a chamber apart from the engine’s working parts. This alone cut fuel use dramatically. With the help of my business partner Matthew Boulton, we brought this engine to market and slowly, but surely, people saw its value. No longer limited to mines, our engines began to drive hammers in forges, looms in textile mills, and even wheels in flour mills. The engine that once labored in darkness now spun the gears of progress.

Factories Rise and Cities Follow

Once steam could turn a wheel, the world changed. Factories no longer needed to sit beside rivers for water power. They could be placed anywhere coal could be delivered. This freed industry from the landscape and allowed it to settle in growing towns, which soon became bustling cities. Steam engines ran day and night, powering textile mills in Manchester, steel works in Birmingham, and breweries in London. Workers flooded into these cities, drawn by the promise of wages, and before long the towns swelled into industrial giants. Smoke rose like banners above the rooftops, and beneath them, the steam hissed and pulsed like a living heart.

On the Rails and Across the Seas

It was only a matter of time before the power of steam left the factory floor. Engineers began to place boilers on wheels, and soon locomotives thundered across the countryside. Railways could carry coal, goods, and people faster than any horse-drawn cart. Canals, once the arteries of trade, were quickly rivaled by these iron tracks. Steam also took to the water. Ships once moved only by wind or oar were now driven by pistons and paddle wheels. Ports grew busier, oceans shrank, and distant lands drew closer. The world was not only working faster—it was moving faster.

The Pulse of Progress

Every improvement brought new challenges. Boilers burst, rails cracked, workers toiled for long hours. Yet steam remained the great equalizer. It did not tire, did not sleep, and did not complain. With coal in its belly and water in its veins, it turned the wheels of the world. By the end of my life, I saw how far it had come—from a crude pump in a mine to the roaring engines that powered nations. And though others would improve it further, adding pressure, speed, and elegance, I take pride in having lit the first fire in the furnace of industrial power.

A Word to the Future from a Man of Steam

Steam did more than turn gears; it turned the course of history. It brought forth both wonder and hardship. But in its rise, I saw the might of human invention—to harness nature, to solve great problems, and to shape the world anew. Let those who follow remember that great power begins with a simple question, and that a better world may lie in the smallest improvement, patiently pursued. Steam rose not in a day, but in steady strokes, and with each puff of vapor came the breath of a new age.

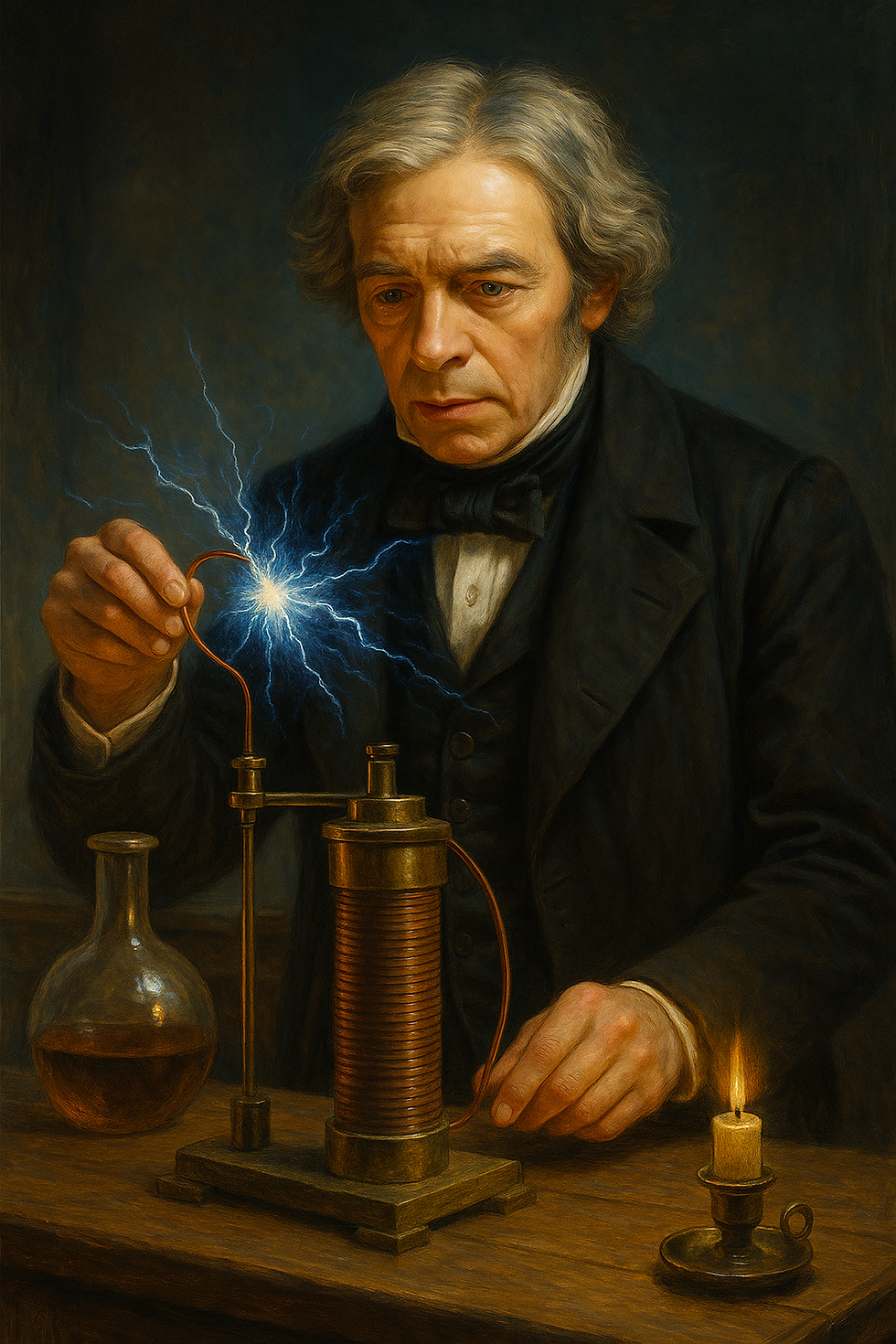

My Name is Michael Faraday: A Bookbinder’s Son with Boundless Curiosity

I was born in 1791, in the heart of London, to a poor but honest blacksmith and his wife. We had little, and I received only the barest formal education. But I had something that no coin could purchase—a hunger to understand the world. As a child, I devoured books whenever I could. At age fourteen, I was apprenticed to a bookbinder. It may seem an ordinary trade, but it gave me a priceless gift: access to knowledge. One book I bound, Conversations on Chemistry, opened my eyes to a universe of invisible forces and astonishing truths. I was captivated. Though I was a tradesman’s apprentice, I began to dream of science.

The Lecture That Changed Everything

In 1812, a kind customer gave me a ticket to attend the lectures of the great chemist Humphry Davy at the Royal Institution. I sat near the back, feverishly taking notes and sketching his apparatus. After the lectures, I sent Davy a bound copy of my notes, along with a letter asking for a position. Remarkably, he replied. When an assistant was injured, Davy hired me as a temporary replacement. I had entered the world of science not through university halls, but through my hands and my perseverance.

Chemistry, Experiments, and Discovery

I spent years in Davy’s service, traveling across Europe, learning from great minds, and assisting in experiments. Eventually, I began my own investigations. In chemistry, I isolated benzene and improved the safety lamp for miners. But it was the invisible realm—electricity and magnetism—that most stirred my soul. I asked: could magnetism produce electricity? In 1831, I answered with a resounding yes. By moving a magnet through a coil of wire, I generated an electric current. This principle, electromagnetic induction, would become the foundation of electric generators.

The Birth of a New Age of Energy

My discoveries opened the door to harnessing electricity not as a curiosity, but as a force of power and industry. While I never built a power station myself, others would use my principles to light cities, drive machines, and power homes. I also introduced the concept of the electric field and worked tirelessly to explain the behavior of electromagnetic forces. I was not a mathematician like my friend James Clerk Maxwell, but I saw patterns in nature and expressed them in language and experiment. The torch I lit, Maxwell would later formalize, giving birth to modern physics.

A Humble Life in Service to Science

Though I was offered knighthood and other honors, I declined most of them. I preferred to remain simply “Mr. Faraday.” I believed that science belonged to all people, not just the elite. That is why I gave hundreds of public lectures—many for children—at the Royal Institution. Perhaps the most joyful of these were the Christmas Lectures, where I lit flames, bent wires, and brought invisible forces to life for eager young minds. My goal was never glory, but understanding.

Final Thoughts for the Generations to Come

When I look back upon my life, I see not a path of privilege but one of curiosity and conviction. I came from nothing but was given the chance to learn, to question, and to experiment. I was a servant of nature’s mysteries. My hope is that you too will see the invisible threads that connect every leaf, every flame, every movement of the stars. If you listen carefully, they will whisper truths that no book alone can teach. Be curious. Be humble. And above all, be unafraid to ask questions no one has dared to ask before.

Smoke & Flame: Coal was King of the Industrial Age – Told by James and Michael

We never met in life, Michael and I, though our lives overlapped for but a few short years. Yet had we sat together in one of those soot-dusted rooms of the Royal Institution or among the clattering machines of a Glasgow foundry, I imagine our conversation would have turned quickly to the fuel that powered both of our legacies—coal. It was coal that fed my steam engines, and it was coal’s hidden energy that would, in time, give rise to Michael’s studies of electricity. Our work may have looked different, but it was shaped by the same black rock pulled from the depths of the earth.

James Watt Reflects on Power from the Pit

When I first began tinkering with the Newcomen engine, coal was already the lifeblood of industry. It warmed homes, smelted iron, and turned the pumps in sodden mines. But it was expensive and dirty, and engines like Newcomen’s used far too much of it. My great ambition was not simply to harness steam, but to do so efficiently, to extract more work from less fuel. With my improved engine, miners could go deeper, haul more coal, and sell it at a better profit. In a strange twist, my engine, born to reduce coal consumption, helped unleash a hunger for coal greater than Britain had ever known.

Faraday Observes the Spread of the Black Vein

Indeed, James, by the time I was a young man conducting lectures on heat and light, coal dust lay thick on Britain’s skin. The coal fields of Newcastle, South Wales, and the Midlands hummed day and night. I remember walking through London in winter and seeing the fog roll in, but it was no natural fog—it was the smog of a thousand chimneys, a heavy breath from the furnaces of progress. Coal gave us light, but it also darkened our skies. I studied the flame of a single candle to understand the nature of combustion, but outside the lecture hall, entire cities burned with the same principle—at a far greater cost.

Watt on Labor and the Price of Power

The deeper the mines grew, the harder the lives of the men and boys who worked them. I had visited such places, where the air was close, the light dim, and danger ever present. Explosions from pockets of gas, collapses of the shaft, and the slow poison of coal dust in the lungs were the wages of power. Steam engines may have lifted water from the pits, but they did not lift the burdens from the workers. And yet, without them, none of it—the factories, the railroads, the cities—would have been possible.

Faraday Considers the Cost Beyond the Mine

And the cost was not only to the body, but to the world itself. Long before there was talk of climate or pollution as we know it now, one could see the toll coal took. Trees fell to clear the way for mines. Rivers darkened. Air thickened. Even the instruments in my laboratory would blacken with soot if the windows were left open too long. Still, the people embraced coal, for it brought warmth, movement, and growth. It made the impossible possible—just as your engines did, James—but not without consequence.

A Shared Vision, A Cautious Hope

We both saw coal as a gift of nature, but also a challenge. It gave us the means to rise, yet warned us of what might happen if we rose too blindly. I, James, gave the world machines that demanded coal. And I, Michael, revealed the forces that would one day move us beyond it. Together, our time stood at the edge of something new—an age where power could be made, stored, and guided in ways even we could not fully imagine.

A Final Thought from Two Men of Energy

Let none forget that coal was the king of its age—not for its beauty, but for its force. It drove the pistons of empire and the wheels of progress. But kings must one day yield to new rulers. As the world moves forward, it must remember both the promise and the peril of coal. Let it be a lesson—not only in what we can burn, but in what we must understand. For every spark we summon, every light we kindle, must be guided by wisdom as well as will.

From the Glow of the Whale Lamp: Whale Oil vs. Coal Gas – Told by Sarah

In my day, the soft light of a whale oil lamp was the very heart of the home. It burned steady and clean, far brighter than a smoky tallow candle. The oil we pressed from the great whales—especially the spermaceti oil from the heads of sperm whales—was our island’s gold. It lit drawing rooms in Boston, parlors in London, and even the halls of kings. From the decks of our Nantucket ships to the storehouses onshore, whale oil was our pride and livelihood. I knew the faces of the men who risked years of their lives to bring back barrels of light from the distant oceans, and I knew the hands of the women who made sure those barrels reached their markets.

A New Flame in the City Streets

But time, like the sea, does not stay still. Long after I passed from this world, a new light began to flicker in the streets of the growing cities. It did not come from a barrel or a ship, but from beneath the ground—coal gas, they called it. Men had discovered how to distill gas from coal and pipe it into streetlamps and even into homes. First in London, and soon in places like Baltimore and Philadelphia, iron poles lined the avenues with glowing orbs, lit not by whale but by coal. The lamps did not flicker with the same golden hue, but they stayed lit through wind and weather, and they could be controlled from a single flame at the mains.

The Turning Tide of Illumination

The change did not come all at once. In many homes, whale oil still reigned for a time. It was trusted, it was familiar, and it bore the smell of far-off salt and bravery. But gas light was cheaper to maintain, easier to supply in the city, and required no years-long voyage to chase elusive creatures through treacherous waters. The cities grew crowded, and whale oil—once a symbol of refinement—began to seem slow and expensive. Gaslight, with its hissing hiss and pale glow, became a sign of progress. Investors turned their eyes from harpoons to pipelines, and the harbors of Nantucket grew quieter.

A Woman's Grief for the Vanishing Trade

It pained me, in memory, to see the decline of the whaling families I once knew. Their sons no longer sailed as they once did. Shipyards emptied. Cooperages fell silent. The oil that had built homes, chapels, and schools was no longer in demand. The world, ever hungry for light, had found a faster way to feed its appetite. What once came from muscle, sweat, and bone now came from fire and stone. It was not better or worse, but it was different. And with that difference came an ending to a way of life I had helped shape.

A Legacy of Light, Passed On

Still, I do not mourn the rise of the coal gas flame entirely. Each age finds its own path to brightness. But I would urge those who look back on mine to remember the cost of every light—whether drawn from the deep ocean or mined from the earth. The glow that fills a room is not born of magic; it is bought by labor, by risk, by sacrifice. So if you light a lamp today, pause for a moment and remember the women who packed the oil, the men who braved the waves, and the world that once turned to the whale to chase away the night.

A Flame to Start the Lesson: The Science Behind Combustion – Told by Michael

When I gave my lecture to the children at the Royal Institution—what is now remembered as my “candle lecture”—I did not begin with machines or great theories. I began with a flame. A simple candle, the kind found in every home. “There is not a law under which any part of this universe is governed,” I said, “which does not come into play and is touched upon in the phenomena of a candle.” Within that small flickering light lies the key to understanding the nature of combustion, the transformation of matter into heat, light, and motion.

The Dance of Elements

What, then, is combustion? At its heart, it is a dance between fuel and oxygen. Whether it is wax from a candle, whale oil in a lamp, or coal in a furnace, the principle remains the same. Heat causes the fuel to break down, releasing gases—hydrogen and carbon among them—which rise and mix with the air. Oxygen, always hungry, seizes upon them. This rapid union releases energy in the form of heat and light. That is the flame you see. It is not solid, nor fixed, but a moment-by-moment expression of chemistry in motion.

The Fuel’s Journey: Wax, Oil, and Coal

In a candle, the wax is drawn up the wick, vaporized, and ignited. In whale oil, the process is much the same, though the liquid fuel is held in a reservoir. Coal, however, is a slower and heavier thing. It burns not in a clean, lifting flame, but in glowing embers, releasing thick smoke and soot. Each fuel has its own character. Oil burns brightly and steadily, but is costly to produce. Coal is abundant and powerful, but it leaves residue—ash, gas, and pollutants that darken both chimney and sky. Efficiency depends not just on the fuel, but on how well we manage the air and heat that feed the fire.

Heat Lost, Energy Gained

One of the great questions I asked in my studies was: how much of what we burn is used, and how much is wasted? In a poorly built lamp or stove, much of the heat escapes into the air. The combustion may be incomplete, meaning not all the fuel is fully consumed. Smoke, then, is the ghost of wasted energy. In steam engines, such as those built by Mr. Watt, improvements were made to retain as much heat as possible, turning more of the fuel’s energy into useful work. This efficiency is not just a technical concern—it is a moral one. To waste fuel is to waste the labor and cost behind it.

The Candle as a Teacher

As I stood before those young faces in the lecture hall, I reminded them that the flame of a candle teaches not only science but imagination. Look closely and you will see the invisible gases rushing in. You will see convection, the rise of hot air and the fall of cool. You will see color changes that reveal temperature and reaction. And perhaps, if you are very attentive, you will begin to wonder what more this humble light has to say about the stars, the engines, and the great furnaces that move the modern world.

A Last Word from the Flame

Let every spark remind you: we live in a world of transformation. Combustion is not destruction—it is change. It is stored sunlight from long-dead forests, captured in coal. It is ancient fat drawn from ocean beasts, alight in the dark of winter. And it is wax drawn from bees, burning on the table of a quiet study. All these flames tell us that energy surrounds us, hidden in matter, waiting to be set free. It is up to you to study it, harness it, and use it with care, for every flame, no matter how small, holds within it the secrets of the universe.

Steam & Sail: Transporting Energy, How Fuel Traveled – Told by James and Sarah

If I, James Watt, had ever sat across from a woman like Sarah Russell—a capable wife of a Nantucket whaling merchant—I imagine we would have found much to discuss. Though we worked in different worlds, mine in the smoky heart of Britain’s industry and hers among the salt-sprayed harbors of America, we were both bound by a common challenge: energy. Not just how it was used, but how it was moved. Whether it was coal dug from the earth, oil drawn from the heads of whales, or crude pumped from beneath the ground, every form of energy had to journey before it could burn. We lived in an age where fuel didn’t simply appear—it had to be fetched, stored, hauled, and delivered.

Sarah Speaks of the Sea and the Whale

Our energy began on the water, James. Whales don’t offer themselves easily. Our men would sail for months, sometimes years, in search of them. The sperm whale was most prized, for it carried in its great head a clear, waxy oil called spermaceti. When a whale was spotted, boats were lowered, harpoons thrown, and the creature brought back to the ship. Onboard, we rendered the blubber in great iron try-pots, boiling the oil down while still at sea. The barrels were then stored deep in the ship’s hold, sealed and ready for the voyage home. Once we reached Nantucket or New Bedford, the oil was offloaded, strained, and placed into casks for shipment. It traveled by wagon, by canal, by river barge—wherever it needed to go. It was not a quick process, but it was steady. And every barrel that reached a distant lamp was the result of blood, sweat, and salt.

Watt Describes the Power Beneath the Soil

Your journeys were long, Sarah, but our burden was no less heavy on land. Coal was our lifeblood in Britain. We pulled it from deep mines, often hundreds of feet below the surface. At first, it was brought up by rope and basket, later by rail systems powered by my own engines. The mines were wet and dangerous, but the coal was plentiful. Once above ground, the coal was moved in carts, sometimes drawn by horses, sometimes by locomotives along wooden or iron rails. In coastal towns, it was loaded onto barges or steamships. In the cities, it was sold by the sack or ton, delivered to factories and homes alike. We built entire canals—like the Bridgewater Canal near Manchester—just to carry coal more efficiently. It was heavy, messy, and left soot on every hand it touched, but it fueled the machines that reshaped our world.

The Arrival of a New Player: Crude Oil

Though it came after both our times, we watched from the shadows of history as crude oil entered the stage. In 1859, a man named Edwin Drake drilled a well in Pennsylvania and brought up oil not from animals or sea, but from the ground itself. No ships or harpoons needed—only a derrick and a pump. This oil was piped, barreled, and shipped across railways and rivers. Refined into kerosene, it threatened to replace both coal gas and whale oil as the lighting fuel of choice. Crude oil could be moved more easily than whale oil, and it burned brighter and cleaner than coal in lamps. Its rise marked the beginning of a new energy empire—one built not on muscle and voyage, but on wells and pipelines.

Sarah on the Burden of Distribution

The difference, James, was not just in how we found the fuel, but in how we prepared the world to receive it. Whale oil required coopers to make barrels, ships to cross oceans, chandlers to blend and sell it. If a barrel broke or spoiled, weeks of work were lost. We relied on trust—of ship captains, merchants, and buyers. Even at its best, whale oil took months to reach a city street. But once it arrived, it was prized, poured into delicate lamps and carefully trimmed wicks. It wasn’t just energy—it was a mark of refinement.

Watt on the Reach of Coal

With coal, we could move faster, though not always more gracefully. The infrastructure of canals, tramways, and later railroads gave us reach. We built depots and coal yards in every city, feeding fires great and small. My steam engines not only burned coal, but helped move it. The fuel became its own freight network, looping through the veins of our industrial nation. It did not spoil, and it was always ready to burn, though its presence was felt in the grime on walls and the black smoke in the sky.

A Shared Reflection on Energy’s Journey

Energy, we both knew, was never simply about the spark—it was about the path it took to get there. From harpoons slicing through sea spray to pickaxes striking stone, from ships crossing the Atlantic to railcars trundling through the Midlands, energy was always in motion. It shaped economies, dictated labor, and decided the rise or fall of industries. Whether we boiled blubber in the Pacific or mined coal beneath the Pennines, we were part of a world pulling power from the far corners of the earth—and bringing it home, barrel by barrel, sack by sack, to chase away the night.

One Final Thought

If you light a lamp today without thought for where the fuel came from, remember us. Remember the journeys, the dangers, the networks of hands that brought that power to your fingertips. Every flame you see has traveled. And every step it took left its mark.

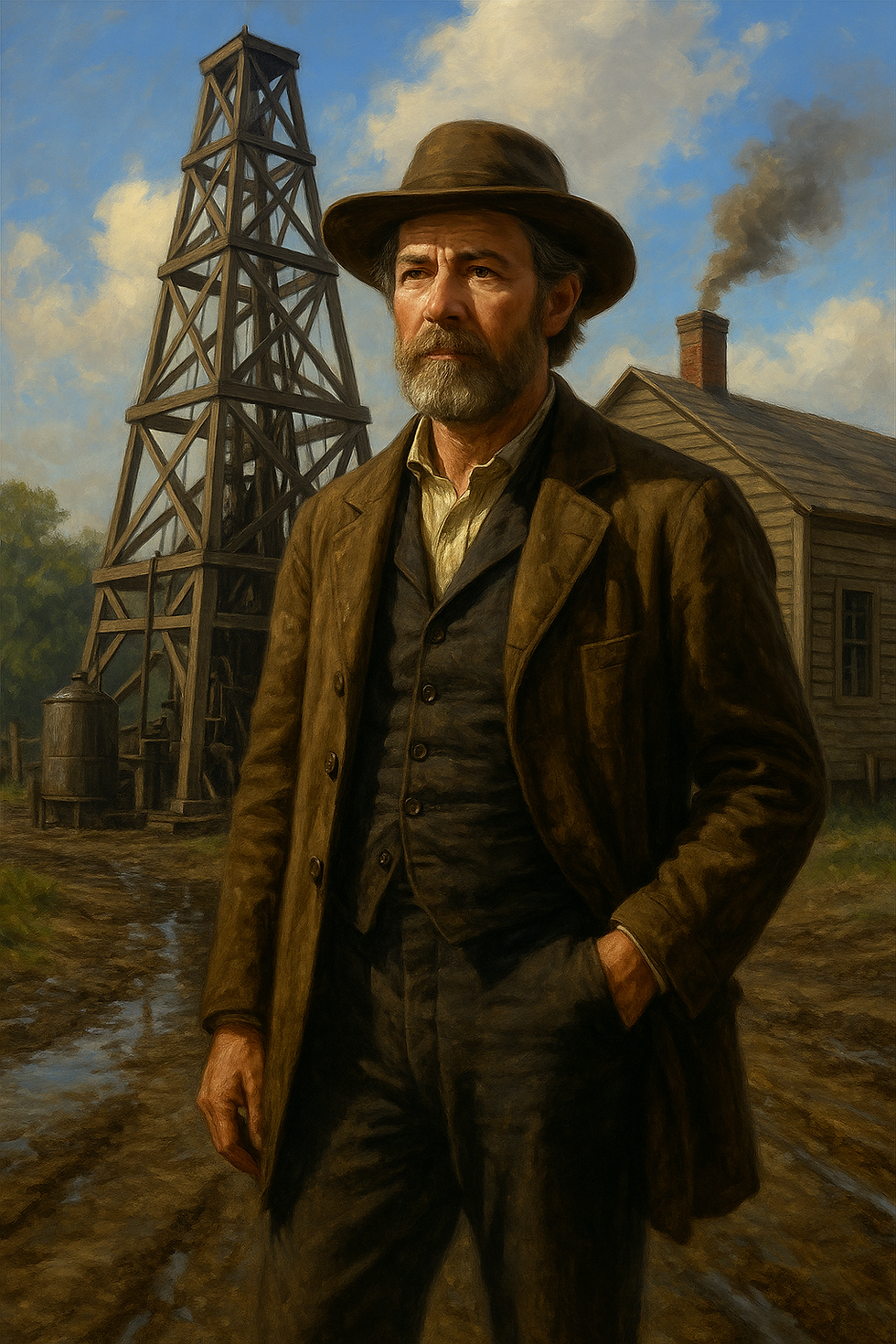

My Name is Edwin Drake: A Humble Beginning and Restless Journey

My name is Edwin Laurentine Drake, and I was born in 1819 in Greenville, New York. I didn’t come from wealth or privilege. My early life was a patchwork of jobs and wandering. I worked as a clerk, a hotel manager, and even a railroad conductor. I never received much formal education, and I often felt like I was drifting, searching for something more meaningful. I didn’t know then that my name would one day be tied to a discovery that would help power the modern world. I was simply a man trying to make a living in a restless young nation.

An Unlikely Opportunity

In the 1850s, I suffered from an illness that forced me to leave the railroads, but that misfortune led me toward destiny. Through a series of chance connections, I was hired by the Seneca Oil Company—not because of any special skill, but because I had a railroad pass that would let me travel cheaply. They wanted someone to investigate oil seeps in Titusville, Pennsylvania, where people had long collected oil from the ground with buckets and rags. At the time, this "rock oil" was mostly used for medicine, but some believed it could be refined into a cleaner, more efficient fuel for lamps—better than whale oil or coal gas.

The Struggle to Drill

The company asked me to find a way to collect larger quantities of oil. I believed the best method would be to drill into the ground—just as people did for salt wells. Many thought the idea was ridiculous. Locals mocked me and called the project “Drake’s Folly.” I had no engineering background, no geological training—just a stubborn belief that it could be done. I hired a blacksmith named William “Uncle Billy” Smith to help me construct a derrick and a steam-powered drill. We fought equipment failures, financial troubles, and skepticism every step of the way.

The Breakthrough at Titusville

On August 27, 1859, at a depth of 69½ feet, we struck oil. It didn’t gush like in the stories you hear now—it rose gently up the pipe—but it was oil, and it could be pumped steadily. That single moment changed the course of history. For the first time, oil could be drawn from beneath the earth in commercial quantities. Soon, barrels were being hauled out of the Pennsylvania hills by the thousands. My simple rig became the blueprint for the modern petroleum industry. Towns sprang up overnight, fortunes were made, and the age of crude oil had begun.

A Legacy Without Fortune

Despite the importance of my work, I did not become a rich man. The company that hired me went bankrupt, and I never held the patents that could have made me wealthy. I was swindled by opportunists and passed over by those who profited from what I began. For years I lived in poverty, nearly forgotten by the world I helped change. Only near the end of my life did the state of Pennsylvania recognize my contribution and grant me a small pension. I died in 1880, not far from the place where oil first flowed beneath my feet.

A Message from the Man in the Mud

I am not a man of science, nor one of privilege. But I proved that bold ideas don’t belong only to scholars or kings. They belong to anyone willing to try, to fail, and to keep digging. My derrick was made of timber and sweat, not silver or fame. But it opened a vein of power that now fuels your cities, your engines, your world. Remember this: the future often begins with a question no one else dares to ask. I asked whether oil could be drawn like water—and that question lit the lamps of a new age.

The First Oil Boom: A Glimpse from the Future – Told by Edwin

My name is Edwin Drake, and though I came onto the scene just as the world was leaving behind the age of whale oil and coal gas, I was there when a new kind of flame was lit. In 1859, in a quiet town called Titusville, Pennsylvania, I drilled what would become known as the first successful commercial oil well. I was no engineer, no scientist—just a man with a stubborn belief that oil could be drawn from the earth like water from a well. Many laughed at me. They called it “Drake’s Folly.” But when the drill struck oil at a depth of 69½ feet, and the thick, black liquid began to rise through the pipe, the world shifted. I didn’t know it then, but I had opened a door to a future far bigger than myself.

From Lamps to Engines

At first, oil was used much like whale oil—for lamps. It was refined into kerosene, which burned brightly and cleanly. No more need for long voyages across oceans or the slaughter of whales. The oil we pulled from the ground could be gathered faster, refined in large batches, and delivered by rail or river. Cities that once depended on barrels from the sea now turned to the land. But crude oil held more than light. As the years passed, clever men found new ways to use it. The invention of the internal combustion engine would turn oil from a lighting fuel into the lifeblood of movement. Trains, ships, and eventually motorcars would run not on steam or muscle, but on the power hidden in every drop of oil.

The Wells Multiply

Once word of my success spread, the hills of Pennsylvania became a frenzy of drills, derricks, and boomtowns. Men rushed in from every direction, dreaming of striking it rich. Oil rigs sprouted like weeds across valleys and ridges. The landscape was noisy, muddy, and wild. Fortunes were made overnight—and lost just as quickly. Pipelines were laid. Refineries rose. Tanker cars rolled out by the hundreds. What began with one well became a network, then an industry, and soon a global race to find the next great oil field.

Replacing the Old Fuels

Before oil, homes had relied on whale oil and coal gas. Factories ran on steam fed by coal, and lamps flickered with animal fat or plant oils. But crude oil was different. It was abundant, easy to transport in barrels or tanks, and rich with potential. It didn’t take long before oil eclipsed whale oil entirely. Whaling ships returned to port for good. Coal, though still powerful, struggled to compete with the versatility and cleanliness of refined petroleum. In cities, gaslights were replaced by kerosene lamps, and soon even they would give way to electric bulbs powered by oil-fired generators.

The Hidden Cost of Convenience

But I must be honest, even in this glimpse toward the future. Oil brought light, speed, and power, but it also brought dependence and danger. Wells sometimes exploded. Spills blackened rivers and fields. Fires raged through careless boomtowns. And the more the world relied on oil, the more it shaped its politics, its economy, and even its wars. In chasing the flame of progress, we sometimes forgot to look behind at what we left burning.

A Voice from the Turning Point

I stood at the edge of two eras—the old world lit by whale oil and coal, and the new world running on oil and engines. My well in Titusville did more than strike a resource—it marked the beginning of a new kind of power. Not just energy, but influence. A barrel of oil came to mean more than gold in some corners of the world. And that meaning only grew with time.

A Lesson for Those Who Light the Future

So to those who study history, who flip on a light or start a car without thinking, I say this: remember that every great leap begins with a single stroke, a single spark, a single well. But also remember that the ease you now enjoy was bought with labor, risk, and change. The first oil boom wasn’t just about finding fuel—it was about unlocking a force that would shape the centuries. Use it wisely. Honor the past, question the present, and never stop asking where your energy comes from—and where it will lead you next.

Beneath the Smoke: Environmental Impacts of Industrial Fuels – Told by All Four

It is a strange thing, this gathering—one of sea and soot, of spark and steam. James Watt stood with soot-streaked hands and quiet pride in the hum of his engines. Edwin Drake, ever practical, leaned on a barrel as if expecting oil to rise from beneath his boots. Michael Faraday held a candle, not yet lit, as if waiting for the moment to explain the fire. And I, Mary Starbuck, stood wrapped in salt-worn cloth, the scent of whale oil still faint upon me. Though we came from different shores and times, we were joined by one pressing question: what price did the world pay for its light?

Mary Starbuck on the Vanishing Giants

I began the talk, not with a sermon, but with memory. When I was a young woman in Nantucket, whales were everywhere. They breached beyond the horizon, their great backs gliding through the water like islands come to life. We hunted them with skill, respect, and desperation. Whale oil lit homes and cities, warmed hearts, and brought profit. But as the years wore on, the whales did not return. The harpoons traveled farther. The voyages grew longer. I saw the sorrow in the eyes of widows and the empty ledgers of merchants. We thought the sea endless, the whales eternal. But they were not. We took too much, too fast, and gave nothing in return. There is no greater warning than a sea gone silent.

James Watt on the Cost of Coal

I listened to Mary with quiet reflection. My work, I said, had been to reduce waste—to take the Newcomen engine and make it more efficient, to use less coal, not more. And yet I could not deny what followed. My improved steam engines, while saving coal in one place, made it possible to use coal everywhere else. Entire cities, once lit by firelight, now throbbed with coal-fed power. But the skies darkened. I had seen it in Birmingham and Glasgow—the soot on the bricks, the ash in the air, the children’s lungs burdened before they reached manhood. Coal built the factories, powered the rails, and drove the ships. It lifted nations, yes—but it also buried clean air beneath its black breath. Still, without it, would we have come so far?

Michael Faraday on Invisible Dangers

Both of them looked to me, and I raised the candle. “This,” I said softly, “teaches more than light. It teaches consequence.” In my lectures, I had spoken of combustion, of the invisible transformation of matter. But smoke, too, is a lesson. In London, I watched the air thicken with coal dust. The instruments in my laboratory blackened. Children coughed in the alleys. We did not yet have the words for it—pollution, respiratory disease, environmental collapse—but we could feel it in our throats and see it in the sky. Even the gaslights we installed in the city streets left behind residue. Every discovery holds potential for progress or ruin. The question is never just what we can burn—but what we leave behind when we do.

Edwin Drake on Oil’s Double Edge

And then I spoke, the newest among them. I never meant to stir the earth as I did. I simply found a way to draw oil from rock. It was cleaner than coal in lamps, easier to move than whale oil, and it lit homes with a steadiness people had never known. But I watched the boomtowns rise and the rivers grow slick with spills. We drilled without restraint, hungry for more. Pipelines carved up the land. Forests were cleared for rigs. And the oil, once flared and spilled without thought, began to seep into the ground, into the water. We had found a genie, and we loosed it without a plan. Oil gave us speed, power, and wealth—but it also tied our future to a finite flame.

A Circle of Reflection

We stood there in a moment of uneasy silence, each of us seeing the part we played. I, Mary, bore the weight of the sea and its wounded creatures. James watched a city rise under smoke. Michael held both fire and caution in his hands. Edwin felt the pressure of an unending rush. None of us could deny the gifts our fuels had given the world—illumination, warmth, movement, connection. But neither could we forget the cost.

Voices in the Smoke and Salt

Mary asked, “Was it worth it?” James answered, “It was necessary, but it need not have been blind.” Faraday whispered, “Knowledge must walk with restraint.” And I, who had opened the earth and let the oil flow, said, “Only if we learn from it.”

A Message to the Ones Who Burn Today

We leave our voices now not as condemnation, but as counsel. Every age chooses its light—and every flame has a shadow. Whether you burn oil, coal, gas, or even harness the sun, remember the stories of those who lit the first lamps. The world is not just fuel to be consumed. It is home, and it must be tended with care.

Fuel and Society—Who Benefited, Who Paid: Discussed by Sarah and James

It was the kind of conversation not often had in the great halls of power or the counting rooms of merchants—but among those who lived close to the sources of energy, the truth could not be ignored. James Watt, the engine-maker of smoky cities, and I, Sarah Russell, a woman who ran the books and barrels of a Nantucket whaling business while my husband chased leviathans across the sea, met on common ground—the question of who truly bore the cost of the world's power.

Sarah on the Weight of the Sea

In my town, it was the sailors who paid the price. The men who set out to sea risked drowning, illness, hunger, and years away from their families. Some never returned. The profits were high, yes—but only for the ship owners and chandlers. The common whalemen, despite risking their lives, often came home with little more than their keep. When oil fetched high prices in Boston or London, it was not the crew who saw the windfall—it was the merchants and refiners. Women like me kept the books, rationed the stores, and held the towns together—but we too were tied to a system built on sacrifice.

Watt on the Shadowed Engine Rooms

In the mining towns and factory districts of Britain, I saw a different kind of hardship. My engines brought new industry, yes—but they also demanded constant fuel, and that fuel came from deep within the earth. The miners, often children and desperate men, worked in cramped tunnels where explosions, cave-ins, and black lung were constant threats. In the textile mills and iron foundries, my engines drove machines faster and longer than any man could endure. Workers toiled for twelve, sometimes fourteen hours a day. Meanwhile, factory owners grew rich. My heart ached to know that while I sought to make engines more efficient, the burden of their power still fell hardest on the poor.

Shared Reflections on Inequality

Sarah nodded, and I returned her gaze. Whether it was the salt-slick whaleboat or the coal-choked shaft, the truth was plain: energy, in our time, flowed uphill. It was pulled from the labor of many and carried profit to the hands of few. Towns sprang up around ports and pits, but they often lacked sanitation, safety, or schooling. Generations were raised in soot and storm, all to keep the lamps burning and the wheels turning.

The Shape of Working Lives

Energy shaped every part of society. In Sarah’s Nantucket, whole families were tied to a single ship’s voyage—its success meant food, its loss meant ruin. In my Glasgow and Birmingham, children left school for mines at eight years old. Tenements grew where factories bloomed, but they were crowded, cold, and dangerous. Fuel brought progress, but it also chained the working class to the demands of industry.

Closing Thoughts Between Colleagues

Still, we agreed that progress could not be undone—but perhaps it could be made wiser. “Efficiency must serve humanity,” I said. “And energy must lift all boats,” Sarah replied. We hoped that future generations would learn from the cost paid by those who dug, hunted, and burned to make the modern world possible.

Watt, Drake, Faraday, and Starbuck Debate: Which Fuel Is Best? – Discussed by All

We four—James Watt, Edwin Drake, Michael Faraday, and Mary Starbuck—stood at the center of a long-burning debate. Each of us had brought a different fuel into the world: steam from coal, oil from whales, crude from the earth, and fire refined through science. The question now laid before us was simple: which source was best for lighting, power, and motion? But the answer, we would discover, was anything but simple.

Mary Starbuck Defends the Whales

“I’ll speak first,” I said. “Whale oil lit homes for generations. It burned clean, smelled sweet, and sustained entire towns and families. My Nantucket thrived on it, and it was earned with courage, not machines. There was no coal dust, no toxic spill. A barrel of whale oil was as valuable as gold. But it was taken too greedily. The seas grew quiet, the whales fewer. I cannot claim it is the best forever—but for a time, it was a noble light.”

Watt Champions the Power of Coal

“With respect, Mary,” I said, “coal brought more than light—it brought motion. Steam engines powered by coal lifted cities, ran mills, drove trains, and drained mines. It was not just about lighting a lamp, but turning the wheels of progress. Yes, it blackened the skies and cost lives, but it built a new world. It could be mined in vast quantities and stored with ease. Without coal, there would be no industry, no iron bridges, no mass production.”

Drake Proposes a New Future

“I understand both of you,” I added, “but crude oil changed the equation. It combined light and power in one. Kerosene replaced whale oil, cleaner and cheaper. And later, gasoline drove engines that coal and whales never could. Oil is abundant, portable, and more efficient than either coal or blubber. It made transportation faster, cities brighter, and industry more flexible. But I won’t lie—it also made us reckless. We burned it faster than we understood it.”

Faraday Argues for Principles, Not Just Fuel

I listened quietly, then stepped forward. “I admire what each of you achieved. But the best fuel is not just the one that burns brightest—it is the one we understand, the one we respect. Science teaches us that combustion is transformation. Whether you burn wax, whale, coal, or crude, the reaction releases heat, light, and gases. But we must ask: what do we leave behind? Soot? Smoke? Poisoned air? The future must move beyond fire. Electricity, drawn from motion, from magnets, from the sun and wind—that is where our minds must turn. Not merely more fuel, but better use.”

A Spirited Closing

We argued gently, each recognizing the others' wisdom. Mary reminded us of the courage behind each barrel. James pointed to the strength of the engine. Edwin showed us the power of oil’s promise. And I, Michael, urged us to consider what lies ahead, not just what lies below.

The Verdict, Left to the Future

In the end, we could not name a single victor. Each fuel had lifted the world in its time—and each had left its shadow. The best fuel, we agreed, is not only the one that burns, but the one that leaves the world brighter than it found it. To those who walk with light today, we say this: choose wisely, for every flame is a choice, and every choice shapes tomorrow.

Gathering at the Crossroads of Flame: Why Oil Won – Told by Edwin

We gathered in a place beyond time, the four of us—James Watt, Edwin Drake, Michael Faraday, and Mary Starbuck—brought together by the enduring question of energy. Not as inventors or icons, but as voices who had once stood at the turning points of their respective fuels. In a circle lit by a single flickering flame, we prepared to debate not only what had worked in our time, but what might serve the world best in the centuries beyond. Our task: to weigh the virtues of whale oil, coal, crude oil, and electricity—for lighting, for power, and for motion.

Mary Starbuck: The Elegance of the Whale’s Gift

I was the first to speak. “I come from a time when the world was lit by what the sea gave us,” I said, voice calm but firm. “Whale oil burned with a soft, clean light. It fueled lanterns in homes, lighthouses on rocky shores, and even the lamps of great cities. It required no machine, only men and ships and bravery. There was something deeply human about it—honorable work at great cost. But I will not hide the truth. We hunted the whales too fiercely. The sea could not replenish them fast enough. It was not a fuel built for eternity. But it was pure, and for a time, it was enough.”

James Watt: The Unstoppable Power of Coal

“I respect the courage of your sailors, Mary,” I replied, “but the world needed more than light—it needed power. Steam engines, fueled by coal, moved the very bones of industry. They spun the wheels of factories, drained the mines, pumped water, drove trains, and carried the weight of empires. Coal was abundant and dependable. You could store it by the ton, haul it by rail, and keep it burning day and night. Yes, it blackened skies and smothered cities. Yes, it sickened the workers who fed the furnaces. But without it, there would have been no Industrial Revolution. It was not beautiful, but it was mighty.”

Edwin Drake: Crude Oil, Swift and Flexible

“I do not come from the sea or the pits,” I said, rising slowly. “I come from the soil. Crude oil, hidden beneath the ground, gave us something new—a fuel that could be turned into light, motion, even chemicals. It burned cleaner than coal, flowed smoother than blubber, and could be refined into kerosene, gasoline, and more. With it came cars, planes, machines that neither steam nor sail could power. It was portable, versatile, and profitable. But I confess, I watched it grow into a beast. Wells bled into rivers. Forests were cleared. We did not think to ration it—we only thought to chase it. Still, no fuel has lit as many homes or carried as many people as oil.”

Michael Faraday: Beyond Fire, Toward Force

I had waited, listening carefully. Then I stepped forward, candle in hand, and lit it. “Each of you brought light to the world,” I said, “but I look beyond flame. Combustion is transformation, yes, but it leaves a residue. Smoke, soot, waste. In my time, I learned to turn motion into electricity, and electricity into light—without burning, without polluting. The candle taught me that energy is everywhere, waiting to be drawn forth not with fire, but with understanding. The future must not belong to what burns brightest, but to what burns cleanest. The sun, the wind, the magnet, the current—these are fuels the Earth does not lose. These are powers we can guide without destruction.”

The Circle Grows Still

For a moment, none of us spoke. Mary looked down, thinking of the whales that once sang through her oceans. James stood still, his fingers twitching as if on a lever, recalling the endless churning of his engines. Edwin stared into the candlelight, seeing oil rise from the earth, black and gleaming. I let the flame flicker, a silent reminder of the science yet to come.

An Answer Without a Crown

None of us claimed final victory. We each had served our time, brought our gift, and witnessed our cost. Whale oil was noble but limited. Coal was powerful but dirty. Crude oil was revolutionary but dangerous. Electricity was still young, but full of promise. Perhaps the question was never which fuel is best—but which is best for the moment, and what follows after.

A Message to the Keepers of the Flame

To those who light the world now, we leave this: Choose your fuel with care, and never forget what it takes to bring it forth. Let your energy lift the many, not just the few. Let it burn not only for power, but for wisdom. And when the old flames dim, do not be afraid to search for a better light.

Comments