11. Heroes and Villains of the Indus Valley - Mahajanapadas and the Second Urbanization (600-300 BC)

- Historical Conquest Team

- Jun 13, 2025

- 35 min read

My Name is Bimbisara: The Diplomatic Builder of MagadhaI am Bimbisara, son of Bhattiya and the first great king of the Haryanka dynasty. I was born around 544 BC in the kingdom of Magadha, a fertile land nestled between the Ganges and Son rivers. From an early age, I was trained in statecraft, warfare, and the Vedic traditions. When I was just fifteen years old, my father saw in me the strength of a ruler and appointed me king, an honor and a burden I carried with both pride and caution. It was not easy to rule at such a young age, but I quickly proved that youth does not always mean weakness.

Conquests and Alliances

Magadha was already a significant realm when I took the throne, but I saw its potential to become the most powerful kingdom of all. My first act was to expand our territory. I annexed the kingdom of Anga, to the east, which gave us access to vital trade routes and resources. I appointed my son Ajatashatru as governor of Champa, Anga’s capital, to secure our hold there. But conquest was not my only method. I also used diplomacy and marriage alliances to strengthen Magadha. I married the princess of Kosala, sister to King Prasenajit, bringing peace between our two kingdoms and a dowry that included the valuable city of Kashi. I also wed princesses from the Lichchhavis and Madra clans, creating bonds with powerful republics and tribes across the northern plains.

Governance and Prosperity

I devoted much of my reign to internal development. I wanted Magadha to be not just large, but strong and prosperous. I centralized the administration, organized tax collection, and encouraged agriculture. Roads were built to connect cities and towns. I fostered trade, which brought riches into Pataliputra, our emerging capital. With the Ganges flowing through our lands, merchants, scholars, and monks traveled with ease, turning Magadha into a center of culture and learning. I welcomed all faiths—Brahmanical rites were respected, but new ideas were rising.

Meeting the Buddha

One of the greatest moments of my life was meeting Siddhartha Gautama, who later became the Buddha. I first heard of him from travelers who spoke of a wise ascetic from the Shakya clan. When he arrived in Rajagriha, I went to meet him. I was deeply moved by his calm presence and profound words. I offered him land at the Bamboo Grove, or Veluvana, to use as a retreat and teaching center. Though I remained a king with many duties, I admired his path of renunciation and wisdom. We maintained a mutual respect throughout my reign.

The Weight of the Throne

But being king was not without sorrow. The peace I sought with all my efforts did not always hold. Court politics could be treacherous, and not even family could always be trusted. Toward the end of my life, I was betrayed by my own son, Ajatashatru. Eager for power, he rebelled against me and imprisoned me. Some say he repented later, some say he did not. I do not speak of him with hatred. Such is the nature of ambition—it burns even in the hearts we nurture.

Legacy and Reflection

Though my life ended in captivity, I look back on my reign with both pride and humility. I laid the foundations for Magadha’s rise, for it would one day become the core of the mighty Mauryan Empire. I built roads, fostered peace, met great teachers, and ruled with both the sword and the olive branch. History will judge me as it may, but I know I served my people and my land with devotion.

If you ever walk the banks of the Ganges near ancient Rajagriha, think of the king who once dreamed of peace, prosperity, and wisdom, and who, for a time, brought them to Magadha.

A World of Great States – Told by Bimbisara

Let me tell you about the world I ruled in—an age of ambition, power, and ideas. During my lifetime, the Indian subcontinent was divided into great realms called Mahajanapadas. “Maha” means great, and “janapada” means the realm or territory of a people or tribe. There were sixteen of these great states, spread across the north of what you now call India, each with its own system of governance, laws, and ambitions. Together, they formed a mosaic of monarchies and republics, of rivals and allies. These were not minor tribes, but powerful regions with organized armies, cities, and economies.

The Sixteen Great Mahajanapadas

Let me name them for you, as any wise ruler of my time would know them well: Anga, Magadha, Vajji, Malla, Kashi, Kosala, Vatsa, Avanti, Chedi, Kuru, Panchala, Matsya, Surasena, Assaka, Gandhara, and Kamboja. Each had a story, and each had its ambitions. My own kingdom, Magadha, was in the lower Ganges valley—rich in rivers, fertile lands, and iron mines. To the west of me was Kosala, my ally and sometimes rival, with whom I sealed peace through marriage. North of Magadha lay Vajji, a confederacy of tribes that proudly called themselves a republic. Further northwest were the ancient lands of the Kurus and Panchalas, whose traditions ran deep into Vedic times. Gandhara and Kamboja, farthest to the northwest, were frontier states touching Persian lands. Avanti, in the west-central region, was another great monarchy and one of my main rivals for control of central India.

Monarchies and the Power of Kings

My own Magadha was a monarchy, as were many others. A monarchy meant a king sat at the center, ruling by divine right, often advised by ministers and priests. My father passed his throne to me, and I ruled Magadha with central authority, collecting taxes, raising armies, and passing laws. Other monarchies like Kosala, Kashi, and Avanti were similar—though their kings varied in strength and wisdom. In monarchies, succession was usually hereditary, and the king’s word was law. But a wise king always consulted his council of elders and Brahmins, for a ruler who ignored advice often fell from grace.

Republics and the Power of the People

Not all Mahajanapadas were monarchies. Some were what we called gana-sanghas—republics or oligarchies. The Vajji Confederacy, to my north, was the most famous example. It included tribes like the Lichchhavis and the Videhas. These republics were governed not by a single king but by a council of elders, often drawn from noble or warrior families. They debated, voted, and ruled together. Decisions were made in large assemblies, and each representative had a say. It was slower, perhaps, than my style of rule, but it gave their citizens a voice. Malla was another such republic, where clans ruled themselves through shared leadership. I admired their unity, even if I found their lack of central command impractical for conquest.

Rivals, Trade, and Ideas

Despite our differences in governance, we all traded with each other, sometimes argued, and sometimes went to war. Goods moved across our borders—horses from Kamboja, textiles from Vatsa, spices from Kosala. So too did ideas. Philosophers and wandering teachers traveled freely, spreading new ways of thinking about life, truth, and the soul. It was in this very climate that men like Siddhartha Gautama and Mahavira arose, challenging kings and republics alike to seek truth beyond power.

Governance and the Future

Looking back, the Mahajanapadas were the seedbeds of India’s future. Monarchies like mine would give rise to great empires. Republics like Vajji showed that shared governance could work in a land of ancient traditions. I ruled with a crown and a sword, but I always watched my neighbors—learning from their debates, their alliances, their mistakes. Even as I expanded my own kingdom, I never forgot that there were many ways to rule, and even more ways to serve your people.

So when you read of these Mahajanapadas in your studies, do not see them as mere names on a map. See them as living experiments in governance, culture, and ambition. I lived among them, ruled among them, and helped shape their destiny. They were my world.

The Land That Gave Us Strength – Told by Bimbisara

Let me begin by telling you what made Magadha not just a kingdom, but the foundation of empires to come. Our strength began with our land. Magadha, cradled between the Ganges and Son rivers, was blessed with fertile soil and abundant water, which allowed our fields to feed large populations and our cities to grow. These rivers were not only a source of life—they were the roads of trade, the lifelines of our kingdom. Merchants, teachers, monks, and soldiers could move swiftly, carrying goods and ideas across our lands. But there was more beneath our feet: the land of Magadha was rich in iron. The hills of Rajgir and surrounding regions gave us the metal we needed to forge stronger weapons, tougher armor, and durable tools. Iron turned our farmers into producers and our warriors into conquerors.

My Rule and the Seeds of Power

When I became king at the age of fifteen, I saw all of this—the rivers, the mines, the towns—and I knew that Magadha was destined for greatness. I worked tirelessly to expand our borders, beginning with the conquest of Anga to the east. That victory gave us access to sea-bound trade through the port of Champa and proved our army could strike fast and hard. I forged alliances through marriage with powerful kingdoms like Kosala and noble tribes like the Lichchhavis. I improved administration, collected taxes efficiently, and centralized authority so the will of the king could be felt in the furthest villages. I did not build greatness for myself alone, but for Magadha’s future.

Ajatashatru and the Edge of War

Though my reign laid the foundation, it was my son Ajatashatru who carried our ambitions to new heights—though at great personal cost. He rose to power in bitter fashion, rebelling against me, but once he wore the crown, he proved to be a fierce and clever ruler. He warred against our neighbors, especially the Vajji Confederacy, which had long resisted Magadha’s influence. To defeat them, he introduced fearsome new weapons: the rathamusala, a chariot fitted with scythe-like blades, and a powerful catapult said to hurl stones across great distances. These were not just tools of destruction—they were symbols of Magadha’s evolving military strength. Ajatashatru also fortified Pataligrama, which would soon grow into Pataliputra, one of the greatest cities in Indian history.

Why Magadha Triumphed

While other Mahajanapadas boasted noble lineages or ancient customs, they lacked the full advantage we possessed. Our geography allowed for trade and agriculture on a grand scale. Our iron gave us unmatched military production. Our rulers—myself, and then Ajatashatru—were determined to unify the region under strong leadership. We used a mix of diplomacy, warfare, and statecraft. While republics like Vajji debated in councils, we acted swiftly. While monarchies like Avanti and Kosala warred among themselves, we expanded and absorbed. Slowly, kingdom by kingdom, we became the most powerful force on the Gangetic plain.

The Road to Empire

I did not live to see the full flowering of Magadha’s destiny, but I knew we had lit a fire that would burn brighter still. After Ajatashatru came other kings—some wise, some cruel—but each one built upon what we started. And then came Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of an empire that would unite most of India and bring fame to the name of Magadha across all lands. He stood on the shoulders of our conquests, our reforms, and our vision.

So when you speak of Magadha’s rise, remember it was no accident. It was the work of rivers, iron, and kings who believed that a strong kingdom could shape the world. I was Bimbisara, and this was my life's work.

The Return of the City – Told by Bimbisara

When I was born, the land was already stirring. Villages had dotted the plains for centuries, but something new was happening—cities were rising again. This was not the first time great cities had flourished in our lands. Long before my time, there were the ancient cities of the Harappans, now ruins whispered of in legend. But now, in my age, a new wave of urban life was spreading across the northern plains of India. We call it the Second Urbanization. Rajagriha, Vaishali, Ujjain—these were not just settlements of huts and thatched roofs. They were centers of power, commerce, religion, and learning. I watched them grow with my own eyes.

Life Within the City Walls

Let me tell you what a city like Rajagriha was like, for it was my capital. It lay nestled in a valley surrounded by five hills, offering both protection and beauty. Roads curved around the hills, and stone walls guarded the heart of the city. There were grand houses made of brick, narrow alleys crowded with stalls, and bustling marketplaces filled with smells of spice and the clamor of trade. Water was brought in through stone channels. People lived in a mix of simple homes and grand courtyards, depending on their station. There were potters, metalworkers, merchants, teachers, monks, and guards. The streets echoed with the cries of hawkers and the chants of wandering ascetics. In the early morning, fires were lit for cooking, and by midday the markets were alive with activity.

Craftsmen, Traders, and the Life of Labor

Every city thrived because of its people. The craftsmen made everything we needed—clay pots, metal tools, gold ornaments, wooden carts, and dyed cloth. Each craft had its guild, a group of skilled workers who passed down their trade from father to son. Traders carried these goods along dusty roads and river routes, reaching other Mahajanapadas and even foreign lands. Grain from the countryside flowed into the city, and in return, the city sent out fine wares and coins. Barter still existed in the villages, but in the cities, coinage had become common. Silver coins called karshapanas circulated in the markets. With coinage came accounting, contracts, and the rise of powerful merchant families. City life was no longer just about survival—it was about wealth, competition, and opportunity.

The Pulse of Urban Prosperity

Vaishali, to the north, was one of the proudest cities I knew. As the capital of the Vajji Confederacy, it was a republic, ruled by an assembly of clan leaders. But even there, despite its different politics, the signs of urban prosperity were the same—walled streets, market squares, and schools where philosophers debated. Ujjain, far to the west in Avanti, grew into a major trading hub, connecting north and south. These cities were not isolated; they were part of networks. Ideas, goods, and people traveled from city to city. Monks carried teachings, and merchants carried silk and salt. As cities prospered, they attracted scholars and spiritual seekers, building parks, temples, and gardens.

The Foundations of a New Era

These cities were not just homes for the wealthy or the rulers. They were the engine of a new kind of life—structured, organized, and interconnected. With permanent settlements came record keeping, with coinage came taxes, and with taxes came kings like me, able to build roads and armies. I knew that cities were the future. They brought together many strands—labor, learning, governance, and faith—and wove them into something far greater than the sum of their parts. It was in these rising cities that the seeds of empire would take root.

So remember, the Second Urbanization was not simply the return of walls and markets. It was the rise of a new way of life—one that would shape the destiny of India for centuries to come. I, Bimbisara, lived in the heart of this change, and I saw the cities of my age glow like stars across the land.

The Web of Commerce – Told by Bimbisara

In my time as king of Magadha, I came to understand that power did not come from swords alone. A strong kingdom needed wealth, and wealth flowed along the trade routes like water down a river. Our land was crisscrossed by paths trodden by merchants, caravans, and riverboats. These routes, some ancient and others newly carved by growing kingdoms, connected distant regions—from the northwestern frontiers to the fertile Ganges plain, from the hills of the Vindhyas to the shores of the eastern seas. It was through these routes that our cities were fed, our artisans enriched, and our influence extended far beyond the reach of our armies.

Rivers as Roads of the Kingdom

The rivers were our first highways. The Ganges flowed through Magadha like a silver ribbon, linking villages, towns, and markets. Boats made of wood and covered with cloth sails carried grain, pottery, spices, and passengers from Rajagriha to distant towns like Kashi and Prayaga. The Son River and its tributaries brought goods from the highlands, including timber and iron. River traffic was swift and efficient, and during the monsoon when roads turned to mud, it was the rivers that kept trade alive. At key ports along the riverbanks, tolls were collected, and merchant houses bustled with activity.

Overland Caravans and Crossroads of Trade

But not all trade moved by water. Great overland trade routes stretched across the land. One major route began in the northwest, in regions like Gandhara and Kamboja, and wound its way through the Punjab, across the Ganges valley, and down into the eastern territories. From the west came horses, gold, lapis lazuli, and woolen goods. From the east we sent back spices, rice, sugarcane, and fine textiles. Another important path connected the Deccan plateau with the northern plains, allowing us to trade with kingdoms like Assaka and Avanti. Merchants often traveled in caravans guarded by hired soldiers, for the roads could be dangerous, with wild beasts and robbers lurking in the forests.

The Treasures of Trade

What did we trade? Everything that could be grown, woven, carved, or mined. Salt from the coasts and deserts, spices from the eastern forests, iron tools from Magadha’s forges, silk and cotton cloth dyed in brilliant colors, beads and bangles of glass and stone, perfumes, pottery, and even medicinal herbs. In the cities, markets were divided by trade—one street for cloth merchants, another for jewelers, another for grain sellers. Trade guilds regulated quality, prices, and apprenticeships. The use of coinage, especially silver karshapanas, made it easier to trade over long distances, and cities like Rajagriha, Vaishali, and Ujjain became centers of wealth.

How Trade Built Kingdoms

It was trade that allowed kingdoms to flourish without endless conquest. With strong trade networks, I could tax goods, fund my armies, and build roads. Trade also brought knowledge—mathematics from merchants, stories from travelers, and philosophies from wandering sages. My court was richer in mind and treasure because of the flow of goods from across Bharatavarsha. Urban centers grew where trade routes crossed, and soon our towns became cities, our villages became markets, and our paths became roads of power.

The Spirit of Exchange

Trade was not only about objects. It was about connection. A pot made in the hills of Anga might end up in the hands of a fisherman in Kosala. A spice picked in the jungles of the east might flavor a meal in Gandhara. Even without empires, we were already a land woven together by movement, exchange, and ambition. And it was from this tapestry of trade that the dream of empire would later rise.

So when you think of ancient India, do not think only of kings and wars. Think of the merchant with his oxen cart, the boatman steering down the Ganges, the market stalls filled with smells and colors, and the roads where strangers met to do business. I, Bimbisara, built my kingdom with this spirit of exchange at its heart.

My Name is Ajatashatru: The Weight of Inheritance

I am Ajatashatru, son of King Bimbisara of Magadha. My name means “one whose enemy is unborn,” and it was said I would rise to power unmatched. Yet greatness does not come without burden. From my earliest days, I was raised in the shadow of my father—a king beloved by his people, a diplomat, and a conqueror. I was taught the Vedas, statecraft, and the use of arms, but ambition grew in my heart more swiftly than wisdom. I began to hunger for power, not in time, but immediately. And so, I did what I have come to regret—I turned against the very man who gave me life.

A Throne Gained in Darkness

Driven by ambition and perhaps poisoned by bad counsel, I imprisoned my own father and claimed the throne of Magadha. Some say he died in that cell by my orders, others say grief took him. Whichever truth stands, I was haunted by it for years. But once the throne was mine, I knew there could be no turning back. I had to prove I was not merely my father’s successor, but a greater king still. The kingdoms around me—Kosala, Vajji, Avanti—watched closely, expecting weakness. I gave them none.

The War with Vajji

The most formidable challenge came from the Vajji Confederacy, a union of tribes and republics, most notably the Lichchhavis. They were strong, organized, and proud. But I was determined to break their power and bring their lands under Magadha. It was a long and bitter war. I could not defeat them by strength alone. Their republican council moved cautiously, and their alliances made them hard to divide. So I used spies, bribes, and cunning, spreading discord among their ranks. At the same time, I introduced terrifying weapons—iron-clad war chariots with blades on their wheels, and catapults that hurled stones with deadly force. Eventually, the Vajji unity cracked, and I claimed victory.

Fortifying the Future

During my reign, I fortified Pataligrama, a small settlement on the banks of the Ganges, and turned it into a mighty city. It would later be known as Pataliputra, one of the greatest cities in the history of India. I saw its potential as a political and economic center, perfectly placed on the river to control trade and movement. I strengthened the army, improved roads, and maintained the iron supplies that had long made Magadha a military power. I did not rule by mercy, but by order. Peace, I believed, came only after submission.

Encounters with the Enlightened

Though I was a man of war, I did not close my ears to the path of wisdom. I met the Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, in Rajagriha. He was calm, humble, and spoke with a clarity that pierced the heart. Though I did not become his follower in my early years, his words unsettled me. He did not seek power, yet kings sought him. His teachings of compassion stood in stark contrast to my own path. I also heard the words of Mahavira, the great teacher of Jainism, who preached nonviolence in a world I had shaped with steel. In my later days, I gave land to monks, listened more to sages, and allowed schools of thought to grow under Magadha’s rule.

A Legacy of Power and Reflection

As I near the end of my life, I look back on my deeds with pride and sorrow. I expanded Magadha to heights my father dreamed of. I made it the strongest of the Mahajanapadas. I set the stage for what would one day become the Mauryan Empire. Yet I cannot forget how I took the throne, nor the blood it cost to keep it. My victories were not just on the battlefield—they were in building a city, uniting a kingdom, and preparing a path for future greatness.

Let history judge me as it will. I was Ajatashatru, the king who rose in fire and shadow, and who, in his final days, searched for the peace he once denied others.

The Rise of Conflict – Told by Ajatashatru

I am Ajatashatru, king of Magadha, and I ruled in an age when the land of Bharat was burning with ambition. The Mahajanapadas, sixteen great realms, were no longer content with peace and tradition. Each desired more—more land, more wealth, more power. And so warfare became a way of life, not just for kings and soldiers, but for entire peoples. Where once disputes were settled by alliances or rituals, now they were settled with blades and blood. The age of great battles had begun, and I was both a product and a master of this new reality.

How Wars Were Fought

Warfare in my time was not as it once had been. No longer were fights mere skirmishes between small bands of warriors. We organized standing armies—divided into infantry, cavalry, chariots, and even elephants. The foot soldiers carried bows, spears, and iron swords. Cavalry—those mounted on swift horses—could strike hard and vanish into the dust. But our pride was in the war elephants, towering beasts armored in metal, trained to charge into enemy lines and trample anything in their path. When they moved, the earth trembled beneath them.

Chariots, too, were symbols of elite power—pulled by two or four horses and mounted by skilled archers. These war chariots became faster, more durable, and sometimes even fitted with sharp blades that spun from their wheels. I myself used such chariots during my campaigns, terrifying the republics that had never seen such instruments of war.

Weapons and Innovations

Iron changed everything. In my father's time, the use of iron was rising, but by my reign it had become central to every battlefield. Iron-tipped arrows pierced armor. Iron blades held their edge in long battles. We forged large catapults, known as mahashilakantaka, which hurled stones the size of a man’s chest over city walls. These were used not only to kill, but to frighten—entire cities could be subdued by the threat of such destruction.

I ordered the creation of a fearsome weapon—chariots fitted with rotating scythes that would mow down rows of enemy warriors. These were not weapons for defense. They were machines of conquest, and they changed how battles were imagined.

Strategy and Siege

Battles were no longer just fought in open fields. We learned to lay siege to cities and fortresses. Walls of stone were built higher, gates were reinforced, and defenders poured boiling oil or shot flaming arrows. To break these strongholds, we used fire, deception, and starvation. I surrounded the great city of Vaishali for years during the war against the Vajji Confederacy. Their unity and defenses were legendary, but I used spies to sow discord within their council. Victory came not just through strength, but through cunning.

We also used diplomacy as a tool of war—breaking alliances, bribing ministers, and turning allies against one another. Warfare, I found, was not merely a clash of weapons. It was a contest of minds, will, and endurance.

The Cost of Victory

But with every war came loss. Fields were burned, towns plundered, and families shattered. The price of my victories was not paid by me alone—it was paid by the farmers whose land became battlefields, the merchants whose routes were blocked, and the children who grew up without fathers. As king, I bore the burden of both glory and guilt.

Warfare shaped our age. It forged kingdoms, shattered republics, and hardened the hearts of rulers. But it also led to stronger states, grander cities, and—eventually—the idea that peace must be stronger than war. I, Ajatashatru, learned this too late, perhaps, but I pass it to you now: the sword can build a kingdom, but only wisdom can keep it.

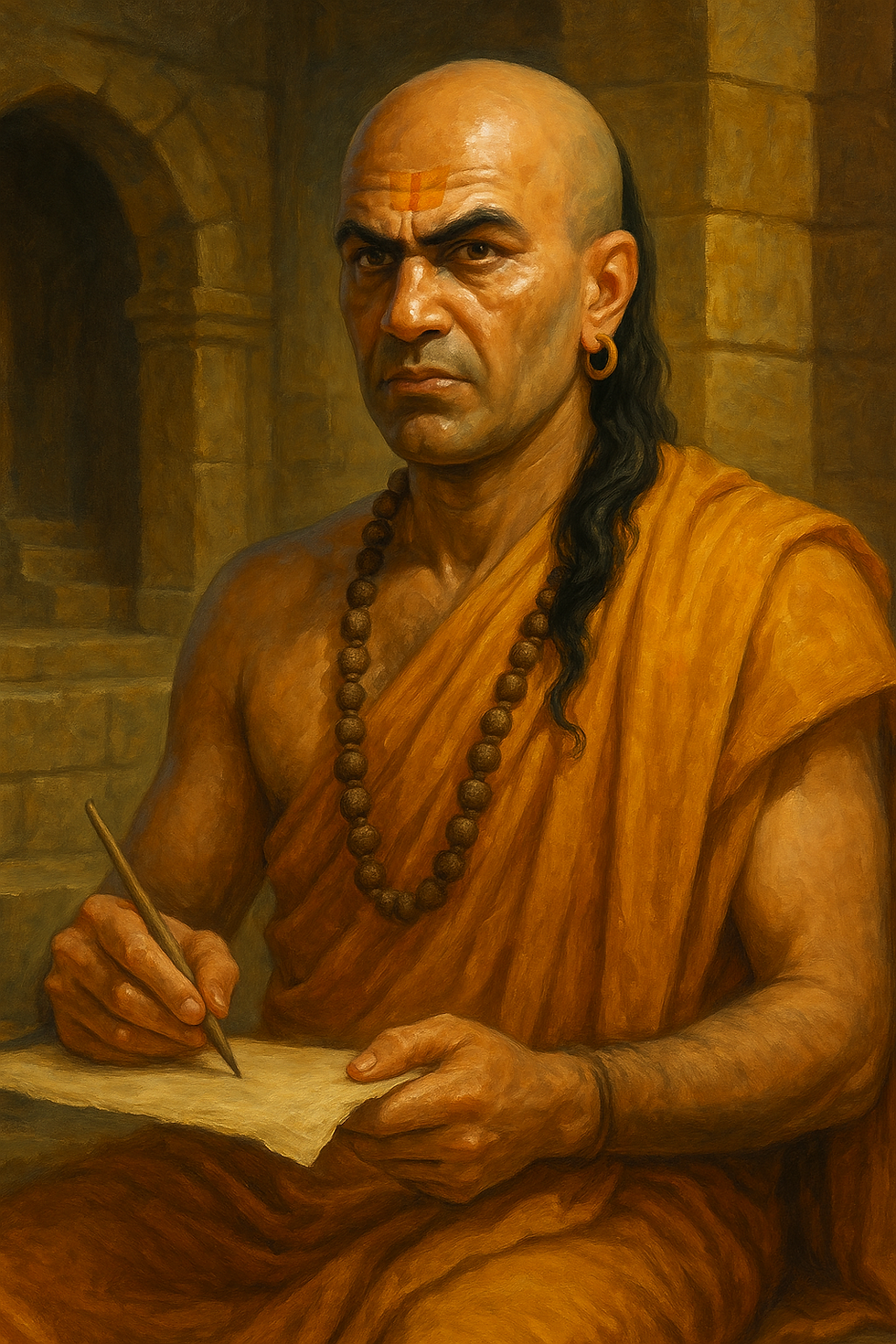

My Name is Kautilya: The Chief Advisor of the Mauryan Empire

I first opened my eyes to the world in a time of political disorder, when kingdoms rose and fell like the changing of seasons. My early education was in Takshashila, the great seat of learning where men studied not only the Vedas, but logic, medicine, warfare, and governance. There, I was trained in the ancient shastras, and I found my mind drawn not to prayer or ritual, but to power—how it is gained, lost, and used for the stability of a nation. I learned to observe not only men, but the systems they created, the flaws in their designs, and the root causes of failure. These studies, and my years among scholars and ministers, shaped the thoughts that would later pour into my life’s work.

A Vow to Uproot the Nanda Dynasty

I came to the city of Pataliputra during the reign of the Nanda dynasty, a family of kings whose authority was maintained by fear and greed. The court was filled with arrogance, and I—ragged, learned, and blunt—was mocked by its rulers. In that moment, I made a vow. I would uproot the Nandas, down to the last root, and plant a ruler worthy of the land. This was not merely revenge. I believed India needed unity, not tyranny. The land was fractured—sixteen Mahajanapadas competing, border raids constant, and invaders watching from the northwest. What we needed was vision, discipline, and strength.

Finding Chandragupta

In my search for a worthy leader, I met a young boy—spirited, sharp-eyed, born of a noble lineage but raised outside of power. His name was Chandragupta Maurya. I saw in him the seeds of a great ruler. I took him under my wing, trained him in statecraft, diplomacy, and war. We went from village to village, gathering allies, learning the pulse of the land. Twice we failed to seize Pataliputra. Twice we were beaten back. But failure is the hammer that sharpens determination. Eventually, with a growing army and the people’s support, we overthrew the Nandas. The throne was no longer theirs. It belonged to the Mauryas.

The Architect Behind the Empire

Though Chandragupta wore the crown, I was his shadow and his mind. I helped him build an empire not on sand, but on order. I devised systems of taxation, trained ministers, and ensured the army was loyal and disciplined. We centralized the administration, ensured roads and trade routes were safe, and established networks of spies to prevent rebellion. Law was firm, sometimes harsh, but always rooted in stability. My goal was not to be liked, but to create a state that would last longer than any man’s life.

The Arthashastra: My Treatise on Power

It was during this period that I composed the Arthashastra, a guide for kings, ministers, and future rulers. It is not poetry. It is not gentle. It is reality. I wrote of war and peace, of diplomacy and espionage, of economics and law. I taught that a king must be both a lion and a fox—strong enough to fight, clever enough to avoid unnecessary bloodshed. I instructed on coinage, weights and measures, trade policies, market regulation, and the duties of every official. My words were not meant for the idle, but for those who would build and protect great nations.

The Later Years

When Chandragupta converted to Jainism and left the throne, I stayed on briefly to guide his son, Bindusara. But I had grown old, and the work of building had already been done. I retired from the court, my hair gray and my beard long, satisfied that I had fulfilled my vow. I had removed the corrupt, raised the worthy, and written a manual that would outlive kingdoms. My life was not one of peace, but one of purpose.

A Legacy of Iron and Ink

Some called me ruthless, others wise. I cared little for praise. What mattered was that I had built something greater than myself—a foundation upon which future emperors could stand. The Mauryan Empire would stretch across the subcontinent, and its strength would be remembered long after its fall. I, Kautilya, was not born a king, but I shaped kings and empires with my mind, my will, and my unbending vision of order. That is my story. That is my legacy.

Growing Pains: Economic Expansion and Trade – Told by Kautilya

I first opened my eyes to the world in a time of political disorder, when kingdoms rose and fell like the changing of seasons. My early education was in Takshashila, the great seat of learning where men studied not only the Vedas, but logic, medicine, warfare, and governance. There, I was trained in the ancient shastras, and I found my mind drawn not to prayer or ritual, but to power—how it is gained, lost, and used for the stability of a nation. I learned to observe not only men, but the systems they created, the flaws in their designs, and the root causes of failure. These studies, and my years among scholars and ministers, shaped the thoughts that would later pour into my life’s work.

A Vow to Uproot the Nanda Dynasty

I came to the city of Pataliputra during the reign of the Nanda dynasty, a family of kings whose authority was maintained by fear and greed. The court was filled with arrogance, and I—ragged, learned, and blunt—was mocked by its rulers. In that moment, I made a vow. I would uproot the Nandas, down to the last root, and plant a ruler worthy of the land. This was not merely revenge. I believed India needed unity, not tyranny. The land was fractured—sixteen Mahajanapadas competing, border raids constant, and invaders watching from the northwest. What we needed was vision, discipline, and strength.

Finding Chandragupta

In my search for a worthy leader, I met a young boy—spirited, sharp-eyed, born of a noble lineage but raised outside of power. His name was Chandragupta Maurya. I saw in him the seeds of a great ruler. I took him under my wing, trained him in statecraft, diplomacy, and war. We went from village to village, gathering allies, learning the pulse of the land. Twice we failed to seize Pataliputra. Twice we were beaten back. But failure is the hammer that sharpens determination. Eventually, with a growing army and the people’s support, we overthrew the Nandas. The throne was no longer theirs. It belonged to the Mauryas.

The Architect Behind the Empire

Though Chandragupta wore the crown, I was his shadow and his mind. I helped him build an empire not on sand, but on order. I devised systems of taxation, trained ministers, and ensured the army was loyal and disciplined. We centralized the administration, ensured roads and trade routes were safe, and established networks of spies to prevent rebellion. Law was firm, sometimes harsh, but always rooted in stability. My goal was not to be liked, but to create a state that would last longer than any man’s life.

The Arthashastra: My Treatise on Power

It was during this period that I composed the Arthashastra, a guide for kings, ministers, and future rulers. It is not poetry. It is not gentle. It is reality. I wrote of war and peace, of diplomacy and espionage, of economics and law. I taught that a king must be both a lion and a fox—strong enough to fight, clever enough to avoid unnecessary bloodshed. I instructed on coinage, weights and measures, trade policies, market regulation, and the duties of every official. My words were not meant for the idle, but for those who would build and protect great nations.

The Later Years

When Chandragupta converted to Jainism and left the throne, I stayed on briefly to guide his son, Bindusara. But I had grown old, and the work of building had already been done. I retired from the court, my hair gray and my beard long, satisfied that I had fulfilled my vow. I had removed the corrupt, raised the worthy, and written a manual that would outlive kingdoms. My life was not one of peace, but one of purpose.

A Legacy of Iron and Ink

Some called me ruthless, others wise. I cared little for praise. What mattered was that I had built something greater than myself—a foundation upon which future emperors could stand. The Mauryan Empire would stretch across the subcontinent, and its strength would be remembered long after its fall. I, Kautilya, was not born a king, but I shaped kings and empires with my mind, my will, and my unbending vision of order. That is my story. That is my legacy.

Usage of Coins in the Economic System: The Mark of Authority – Told by Kautilya

I am Kautilya, known to some as Chanakya, and if you would understand how a kingdom grows strong, do not begin at the gates of its fortresses but at the scales of its markets. Among the many tools I used to build and guide the Mauryan Empire, few were as powerful as the humble coin. It may seem small, but a coin is a promise—a symbol of order, trust, and royal authority. When I helped shape the economy of Magadha and the empire beyond, I placed great importance on coinage, not merely for trade, but for unifying the economy and solidifying power.

Punch-Marked Coins: A New Age of Exchange

Long before I was born, punch-marked coins had begun to circulate in the Mahajanapadas. These were pieces of silver, roughly cut and stamped with symbols—each punch a mark of identity, authenticity, or authority. They did not show the face of kings as later coins would, but they bore the marks of the state or guild that issued them: sun symbols, trees, animals, or geometric shapes. In my time, these punch-marked coins had become the backbone of urban trade. They were accepted widely, weighed carefully, and trusted more than bartered goods.

Why Coins Changed Everything

Before coinage, trade relied on barter, and the value of one item against another was always in dispute. Coins introduced standardization. A karshapana, properly minted and weighed, had a known value. It could be taxed, saved, paid as salary, or used to buy grain, cloth, or cattle. In my Arthashastra, I wrote detailed regulations to control the purity of metal, to punish counterfeiters, and to fix exchange rates. Coins allowed a merchant from Kalinga to trade easily with a buyer in Gandhara. They made wealth portable and prices visible. They also made taxation efficient, for coinage brought all commerce under the gaze of the state.

The Marketplace and Economic Activity

Cities and towns in my day were lined with markets—panya shalas—each filled with the hum of trade. We had separate quarters for different trades: jewelers, potters, weavers, iron smiths, and spice sellers. I appointed superintendents to watch over the markets, check weights and measures, and ensure that prices were fair. Prices were not left to chaos; they were guided by the state to ensure stability. The presence of coinage allowed daily trade to flourish, from small handcrafts to bulk commodities.

The Rise of Early Banking

As coinage spread, another system quietly grew alongside it: the beginnings of banking. Wealthy merchants and guilds began to lend money with interest. Deposits were held by trusted individuals and institutions. Notes and records were written to represent stored coin. I ensured these practices were monitored and regulated. A coin held in trust was to be protected by law, for without confidence in such systems, economic life would crumble. Lending at unjust interest was forbidden. Debtors were to be treated with rules, not ruthlessness.

Coins as Instruments of State Power

But a coin is more than metal. It is a message. Every punch-mark on a coin told the people who ruled the land and protected the market. By circulating coins bearing the marks of Magadha and the Mauryan state, we declared our sovereignty. As the empire grew, so too did our coinage. Wherever a merchant saw one of our coins accepted and honored, he knew he stood within the reach of imperial order. Thus, coins did what armies could not: they bound distant provinces to the center not by fear, but by trade.

The Legacy of the Coin

In the world I helped shape, coinage turned markets into engines, brought rulers into the homes of commoners, and laid the groundwork for all organized economic life. Let it be remembered that a just coin, fairly weighed and widely trusted, is one of the greatest inventions of civilization. I, Kautilya, guarded the treasury not for gold’s sake, but because from it flowed peace, progress, and prosperity. The coin was our silent servant and our loudest statement. Let future rulers never forget its value.

My Name is King Prasenajit of Kosala: The Patron of Debate I am Prasenajit, king of the ancient and noble land of Kosala. I was born into the illustrious Ikshvaku dynasty, the very same line from which Lord Rama was said to descend. My father, King Mahakosala, was a wise and just ruler who laid the foundation for the strength and prosperity of our kingdom. From my earliest days, I was raised to understand that kingship was not just a right, but a sacred duty—a burden to be carried with wisdom, restraint, and fairness. I studied the Vedas, politics, and diplomacy, and I was trained in arms and governance under the best teachers of our court.

A Kingdom at the Heart of India

Kosala lay in the fertile plains of the Ganges, stretching from the Himalayas to the banks of the Sarayu River. Our capital, Shravasti, was a city of great learning, commerce, and religious life. Surrounded by powerful neighbors like Magadha and Vatsa, I knew that I must rule with both strength and tact. Our lands were rich with trade—salt, textiles, and grain moved freely across the roads and rivers. The marketplaces were alive with the voices of merchants and philosophers. My rule saw both challenges and golden years, and I worked always to maintain balance between prosperity and peace.

Rivalries and Alliances

Among the greatest political matters of my reign was my complex relationship with King Bimbisara of Magadha. He was as ambitious as he was skilled. To secure peace and strengthen ties between our two kingdoms, I gave my sister in marriage to him. In return, he granted me the prosperous city of Kashi as dowry. But as fate would have it, tensions still arose, especially after the execution of Bimbisara by his son, Ajatashatru. The friendship between our two courts gave way to war and rivalry. I fought Ajatashatru, but in time, peace was restored through my daughter's marriage to him. In the great chessboard of politics, alliances shifted with every generation, but I always placed the security of Kosala above pride.

A Patron of Wisdom and Faith

The greatest privilege of my reign was not in war or politics, but in thought. I lived during a time of profound spiritual awakening. The Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, walked the earth during my lifetime, teaching in the forests and cities of our region. I met him in person, and I became one of his devoted lay followers. Though I continued to uphold the traditional duties of a Kshatriya king, I came to believe deeply in the value of nonviolence, compassion, and truth. I provided support for the monastic community and helped spread his teachings across Kosala. Yet I also respected other paths, including those of the Brahmins and the Jains, believing that a wise king must allow his people the freedom to seek the truth in their own way.

Trials and Reflections in Old Age

No king’s life is free from sorrow. In my old age, I faced betrayal within my own court and the pain of losing loved ones. There were years when the land suffered from drought and discontent, and I questioned whether I had truly done enough. Yet I found peace not in palaces or ceremonies, but in quiet reflection on the teachings I had heard beneath the Bodhi tree and in the company of sages. The more I ruled, the more I realized that greatness lies not in conquest, but in justice and inner balance.

My Legacy to the World

When I look back upon my life, I see a ruler who sought harmony in a world often torn by conflict. I upheld dharma as best I could, protected my people, and gave my kingdom years of stability during a time of great change. I stood at the meeting point between ancient traditions and new wisdom, and I opened the doors of my court to both. My name may not be remembered with the might of conquerors, but I hope it is remembered with the quiet respect given to those who listened, who learned, and who led with a steady hand.

The Age of Change – Told by King PrasenajitThe air itself seemed heavy with new ideas, and the minds of men turned inward as much as outward. Though the Vedas and Brahmins still held sway over the spiritual life of our people, the sounds of recitation and ritual no longer drowned out the quiet murmurs of doubt. A great transformation was beginning to take root, and I stood in the heart of it. The people were restless—not with violence, but with yearning. They sought a path not covered in the ash of sacrifice or buried beneath layers of priestly command.

The Cracks in the Old Ways

The Brahminical order, based on ancient Vedic tradition, had ruled spiritual thought for generations. It emphasized complex rituals, performed in precise ways, with offerings of grain, ghee, and animals. Only Brahmins could officiate, and only those born into higher varnas could expect spiritual progress. The caste system had hardened by my time, and with it came growing discontent. Many began to ask why birth should decide destiny. Why should a merchant or a farmer be barred from sacred knowledge? Why must liberation from suffering come only through fire rituals and the guidance of priests? These questions echoed from the cities to the forests.

Voices from the Wilderness

It was into this world of questioning that two great lights emerged—Vardhamana Mahavira and Siddhartha Gautama, known later as the Buddha. Both were born into Kshatriya families, like mine, yet they walked away from palaces and politics to seek truth. They did not reject the quest for liberation, but they offered new paths to it. Mahavira taught the way of nonviolence, self-restraint, and renunciation. He spoke of karma not as something managed through ritual, but as a force tied to every thought, word, and action. His path was severe, demanding the shedding of all possessions and the embrace of absolute purity.

Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, offered another vision. He taught that suffering was part of life, but not unending—that it could be ended through understanding, ethical living, and meditation. His teachings needed no sacrifice, no caste, no priestly blessing. They called instead for compassion, mindfulness, and moderation. When I met him in person, I saw not a rebel, but a calm presence who spoke with clarity and peace. He asked not for gold or titles, but for ears that would listen and hearts that would reflect.

The People's Response

The people heard these new voices and came willingly. Merchants, farmers, artisans, even nobles—many were drawn to these teachings because they offered dignity and hope to all. In Jainism and Buddhism, they found meaning that was not bound to ritual or rank. Monasteries and gatherings appeared across the land. Cities like Shravasti and Rajagriha became centers of learning, debate, and pilgrimage. The traditional Brahmin class did not vanish, but it now shared the stage with those who spoke not of sacrifice, but of self-discipline and direct experience.

My View as King

As a king, I did not take sides in matters of belief, but I understood their power. I supported the monks and gave land for viharas. I still honored the Brahmins and their place in our history, but I also saw in these reformers a light that could reach beyond caste and creed. I believed that a wise ruler must not only guard borders and collect taxes, but also allow truth to find its voice among the people. For if we silence seekers, we blind ourselves to the future.

The Roots of Reform

So what caused this great wave of change? It was not rebellion, but reflection. It came from a people weary of exclusivity, hungry for meaning, and ready to walk new paths. The rigidity of the caste system and the weight of elaborate ritual had left many spiritually dry. The reformers gave them water. And as king of Kosala, I witnessed the transformation not as an observer from afar, but as one who welcomed it at my gates.

The Seeker from the House of Kings – Told by King Prasenajit

Among the wandering sages and renunciants of my time, few were as remarkable as Vardhamana, the man who came to be known as Mahavira—the Great Hero. Born into the noble Kshatriya clan of the Jnatrikas, near the land of Vaishali, he was the son of a chief and raised in comfort and learning. Like Siddhartha Gautama, his early life was filled with privilege, but his spirit was drawn not to luxury, but to liberation. At the age of thirty, he left behind his home, family, and status, seeking the truth of existence.

The Path of Renunciation

For twelve long years, Mahavira wandered through forests, villages, and cities. He wore no clothes, carried no possessions, and lived in the harshest of conditions. He endured hunger, mockery, and the searing heat of the sun, testing his endurance in every way. He believed that the soul was bound by karma—subtle particles of matter attracted by selfish action and ignorance—and that only through strict control of body and mind could these bonds be shed. His path was not one of comfort. It was of discipline, silence, and relentless self-purification. In time, he attained what his followers call kevala jnana—pure, infinite knowledge.

Ahimsa: The Heart of Jain Teaching

Of all Mahavira’s teachings, none struck me more deeply than his emphasis on ahimsa, or nonviolence. This was not merely the avoidance of killing; it was the refusal to harm any living being in thought, word, or deed. Even the smallest insect or plant was to be treated with care. For him, every soul—whether in a man, a bird, or a worm—was sacred. He taught that violence, whether for food, anger, or ignorance, tied the soul to the cycle of birth and death. His monks carried brooms to sweep the path before them, lest they crush tiny creatures. They wore masks to avoid harming even airborne insects. In this, Mahavira gave us a vision of radical compassion.

The Five Great Vows

Mahavira taught his followers to take five great vows, known as the mahavratas. The first was ahimsa, nonviolence. The second was satya, truthfulness in all speech. The third was asteya, not stealing or taking anything not freely given. The fourth was brahmacharya, celibacy and control of the senses. And the fifth was aparigraha, non-attachment to material possessions. These vows formed the core of Jain practice, especially for monks and nuns, though even laypeople were encouraged to follow them to the best of their ability. In contrast to the elaborate Vedic rituals, Mahavira’s path asked for inward change, ethical behavior, and deep self-restraint.

Jainism and the Vedic World

The world of the Vedas, which I too was born into, revolved around fire sacrifices, hymns, and the authority of the Brahmins. Spiritual progress was thought to depend on birth and proper ritual. The castes were sharply divided, and the gods were invoked through sacred chants. But Jainism offered something different. It gave access to liberation to anyone, regardless of caste or status, if they were willing to walk the path. It rejected the sacrifice of animals, and indeed any harm to life. Where the Vedic tradition looked upward to gods, Mahavira looked inward to the soul. Where the Vedas called for offerings of fire and ghee, Mahavira called for silence and renunciation.

My Reflections on the Great Teacher

As king, I could not follow Mahavira’s path—I was bound to my duties, my palace, and the governance of my people. But I welcomed Jain monks in my realm, and I saw the quiet strength of their example. Their discipline, honesty, and peace brought stability to society. Many of my subjects became followers, and their presence helped lessen violence and greed in the land. I do not believe there is one single path for all souls, but I saw in Mahavira a man who had conquered his passions and reached the summit of spiritual clarity.

A Light for the Ages

Mahavira’s teachings continue to guide those who seek liberation through discipline, harmlessness, and truth. He asked for no temples, only pure hearts. He demanded no blind loyalty, only self-awareness. He lived not to rule, but to free. I, Prasenajit of Kosala, lived in his time, listened to his disciples, and watched the seeds of Jainism take root across the land. Let those who study his path do so with respect, for he walked it not with words alone, but with every step of his life.

The Attacks on the Caste System by Religion – Told by King Prasenajit

I am Prasenajit, king of Kosala, and from the moment I was born, I lived under the canopy of an ancient social order—the varna system, which placed each person into one of four broad castes: Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra. It was said this order had existed since the beginning of time, born from the body of Purusha. The Brahmins, from the mouth, were the priests and scholars. We Kshatriyas, from the arms, were rulers and warriors. The Vaishyas, from the thighs, were traders and farmers. The Shudras, from the feet, served the rest. This system gave structure to society, but over time it became rigid, limiting a person’s worth to their birth alone.

The Weight of Ritual and Division

In my court, Brahmins performed sacrifices and chanted Vedic hymns, declaring that liberation could only be achieved through the correct performance of rituals. These ceremonies were elaborate, expensive, and beyond the reach of common people. The lower castes, particularly the Shudras and those considered outside the varna altogether, were often denied access to spiritual teachings. They were told that their very birth disqualified them from seeking truth in this life. Many accepted this silently. But not all.

The Challenge of the Wanderers

During my reign, two great teachers walked the roads of India—Mahavira of the Jains and Gautama, the Buddha. They came not with armies, but with questions. They asked: Can a person’s birth truly determine their purity? Is the soul bound forever by the caste of the body? They saw suffering in the eyes of the poor and the outcast and said that truth belonged to all who sought it, not just to those born into privilege. In their gatherings, a merchant sat beside a servant, a prince beside a farmer. They judged people not by lineage, but by their conduct and their effort toward wisdom.

Ethical Living Over Sacred Lineage

The teachings of both Jainism and Buddhism centered not on ritual, but on ethical living. Mahavira called for ahimsa—nonviolence toward all beings—and personal restraint. The Buddha spoke of the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path, teaching that liberation came through right speech, action, livelihood, and thought. Neither demanded that one be born into a certain caste to practice. They demanded, instead, that one be sincere. This message resonated deeply, especially with those who had been told their birth made them spiritually inferior.

Personal Responsibility and Universal Compassion

What set these paths apart was their emphasis on personal responsibility. No priest could absolve one of wrongdoing. No sacrifice could wash away harmful intent. Each person, regardless of caste, was the author of their own karma. And through right action, anyone—yes, anyone—could seek liberation from the cycle of birth and death. They taught compassion not for one's own group, but for all living beings. This idea, radical in its simplicity, began to stir change in the hearts of many.

A King's Reflection

As a ruler, I could not abandon the caste order entirely, for society rested upon its framework. But I began to see its flaws more clearly. I welcomed monks into my court who spoke not of fire altars, but of inner peace. I allowed those from humble origins to seek knowledge and spiritual refuge. My city, Shravasti, became a place where new voices could be heard. The presence of these teachings brought a gentler rhythm to our kingdom, one shaped more by moral duty than inherited status.

The Quiet Revolution

This was not a violent revolution. It did not tear down temples or burn scriptures. But it turned the hearts of many. By shifting the focus from birth to behavior, from ritual to reason, from caste to compassion, these new movements planted the seeds of social change. They reminded us that wisdom may rise from any soil and that the light of truth cares not for the shape of the vessel it fills.

I, Prasenajit of Kosala, watched these teachings spread like dawn across the land. And though I was born into power, I found myself learning from those who had renounced it. Let those who come after me remember that society must be guided by both order and justice, but justice must always begin in the heart.

Comments