11. Heroes and Villains of Ancient Africa: The Niger River Culture: From Ancient Times to Islamic Era

- Historical Conquest Team

- Aug 16, 2025

- 35 min read

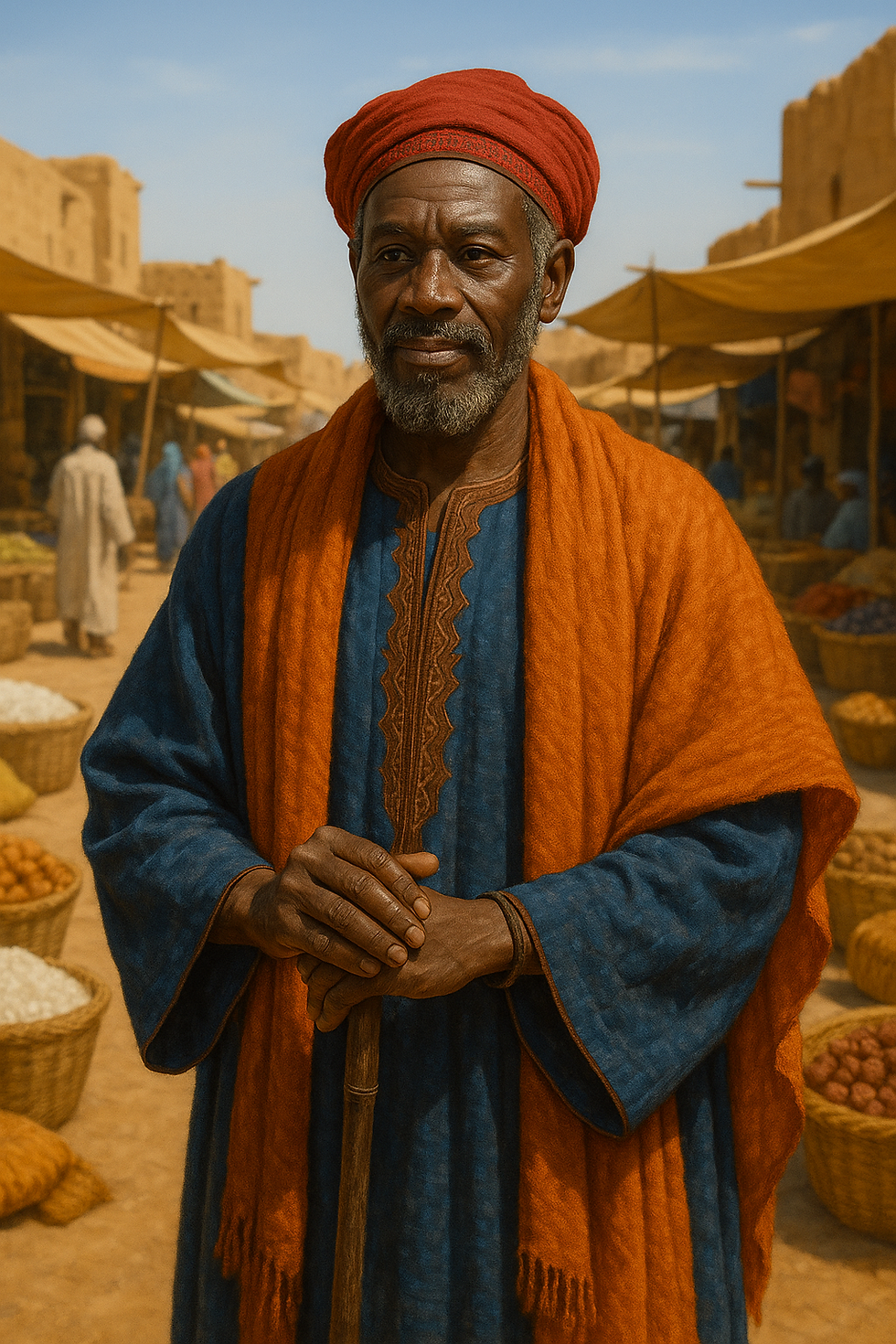

My Name is Za Alayaman (c. 8th–9th century AD): Founder of the Za Dynasty of Songhai Rule, Along the Niger River

I was not born along the banks of the Niger River, but far to the northeast, in the land of Yemen. My life began in the shadow of mountains and the scent of frankincense, yet my fate lay across deserts I had never seen. Stories of the great river that wound through the heart of a fertile land reached our ears through merchants and travelers. It was said that its waters fed mighty cities and that the people there traded gold, salt, and grain. I felt a calling, as though my path was meant to lead me there.

The Crossing of the Desert

My journey to the Niger was long and harsh. I joined caravans that wound their way across the Red Sea and through the Sahara, enduring scorching days and nights chilled by the wind. I traveled with traders, warriors, and wanderers, each drawn westward by opportunity. Along the way, I learned the customs of the Berber guides, the rhythms of the caravan drums, and the art of survival where water is more precious than gold.

Arrival at Gao

When I reached Gao, I found a land of promise. The Niger flowed broad and steady, its waters carrying fishermen’s canoes and merchant boats heavy with goods. The markets were alive with voices speaking many tongues—Songhai, Mandé, Tuareg, and others. Gao was a meeting place of cultures, yet it lacked unity under a strong and just ruler. The people welcomed me as an outsider with fresh vision, and I began to weave bonds between the different clans.

Founding the Za Dynasty

With the trust of the people and the loyalty of warriors, I established the Za dynasty. My rule was not only about power but about harmony between the diverse peoples of the Niger bend. I encouraged trade by securing caravan routes and protecting the river’s markets. I worked to strengthen Gao’s position as a central hub for goods traveling between the forest lands in the south and the salt-rich deserts to the north.

Blending Worlds

Though my origins were far from the Niger, I came to see myself as part of its life. I married into local families, listened to the griots who carried the history of the land, and learned the wisdom of the river’s cycles. I brought with me ideas from Arabia—new ways of governance and faith—but I also honored the traditions that had shaped this region long before my arrival.

A Lasting Foundation

My descendants carried on the Za name, ruling Gao for generations. Some would adopt new faiths, others would face challenges from rival powers, yet the dynasty I began remained tied to the Niger’s heartbeat. My journey was one of crossing worlds, from the mountains of Yemen to the great river of Africa, and of leaving behind a legacy that endured in the flow of history.

My First Glimpse of the Niger River: Origins and Geography – Told by Alayaman

When I first arrived in the lands of the Niger, I was struck by its vastness. In my homeland of Yemen, water flowed in narrow wadis that dried in the heat, but here, the river was a living force, wide and steady, bending and curling like a serpent across the land. I learned quickly that its journey began far to the southwest, in the Fouta Djallon highlands of what is now known as Guinea. From there, it wound north into the dry Sahel before curving back south, a great arc that brought life to countless peoples.

The Rhythm of Flood and Retreat

The Niger had its own calendar, marked not by the moons alone but by its rising and falling waters. Each year, when the rains came to its headwaters, the river would swell, spilling into the inland delta. This flood turned plains into shallow lakes and marshes, rich with fish and fertile silt. Months later, as the waters retreated, they left behind dark, nourishing soil ready for planting. The farmers understood this rhythm as well as the herders and fishermen did, for all depended on its gift.

The River’s Many Worlds

Traveling along the river revealed its many faces. In the inland delta, its channels spread into a maze of waterways, home to Bozo fishermen and their canoes. Downstream, the banks were lined with villages that grew millet, rice, and sorghum, their fields lush after the flood. Beyond them, the river narrowed and quickened, cutting through rocky lands before widening again into slow, deep stretches where traders could sail their goods to distant markets. Each bend of the Niger seemed to hold a new world.

How the River Shaped Settlements

It was no surprise that towns and cities grew where the river gave the most. Gao, the city I would one day rule, flourished where caravans from the desert met the boats from the south. Other towns, like Djenné and Timbuktu, rose from the river’s bounty and the trade it enabled. Villages hugged the fertile floodplains, their granaries filled with the harvests brought by its waters. In truth, the Niger was more than a river—it was a road, a market, and a wellspring of life.

The Bond Between River and People

I came to understand that the Niger was the heart of this land, and its pulse was felt in every season. Without its floods, the soil would harden and crack. Without its flow, the fish would vanish and the trade would falter. In my years as ruler, I sought to protect the routes along its banks, for whoever safeguarded the river safeguarded the people. The Niger’s geography was not just a fact of the land—it was the foundation upon which kingdoms, alliances, and cultures were built.

Rise of Early Niger River Civilizations (Gao, Djenné, Timbuktu) – Told by Alayaman

When I came to the Niger bend, the cities that would one day be famed across the desert were still growing into their power. Gao, where I would settle, was already a place of gathering for traders, fishermen, and herders. Djenné, far to the southwest in the inland delta, stood as a meeting point where river boats and caravan paths converged. Timbuktu, at that time a modest settlement, was known more as a resting place for nomads than as the seat of learning it would one day become. Yet even then, I could see that these places were poised to shape the future.

Gao and the Power of Trade

Gao’s strength lay in its position. Here, the Niger’s waters carried goods from the fertile lands of the south, while the desert paths brought salt, copper, and cloth from the north. Traders of many tongues met in its markets, and alliances were often sealed over the exchange of goods. By securing Gao and uniting its people under the Za dynasty, I helped transform it from a busy river town into a true seat of authority, a place where commerce and leadership intertwined.

Djenné and the Mastery of the Inland Delta

Djenné was different. It rose from the heart of the inland delta, surrounded by waterways rich in fish and soil perfect for crops. Its people were masters of the river’s cycles, planting rice and millet when the waters retreated and fishing when the floods came. Djenné’s traders moved goods by canoe to distant markets, making it a natural center of exchange. The city became a bridge between the cultures of the forest belt and those of the Sahel, and its wealth drew craftsmen, scholars, and farmers alike.

Timbuktu’s Humble Beginnings

In my day, Timbuktu was not yet the famed city of scholars. It began as a seasonal camp for Tuareg herders, its location at the edge of the Sahara giving it a role as a link between the desert and the river. As trade increased along the Niger and across the sands, Timbuktu grew from a cluster of tents into a settlement where merchants could store goods, rest their caravans, and prepare for journeys onward. Its true rise would come generations later, but its roots were already taking hold.

The Ties That Bound the Cities

What made these cities flourish was not just their location, but their connection to each other through the river. Goods could flow from Gao to Djenné and beyond, while ideas, stories, and skills traveled the same routes. A weaver in Djenné might work with cloth dyed from plants grown far upriver, while a merchant in Gao could sell salt that had passed through Timbuktu’s gates. Together, they formed a chain of prosperity that bound the peoples of the Niger into a shared destiny.

The Foundations of Empire

In uniting Gao and strengthening its trade, I knew I was laying part of the groundwork for something greater than my own rule. These cities were more than isolated centers of wealth—they were pillars of a growing network of power and culture. In their markets and harbors, the seeds were sown for the great empires that would one day rise, carried forward by the enduring flow of the Niger River.

My Name is Ibn Battuta (1304–c. 1369): Moroccan Explorer Who Came to Mali

I was born in the bustling port city of Tangier in the year 1304, where the scent of the sea mixed with the spice markets and the calls to prayer. My family were scholars and judges, and from a young age, I was taught the ways of the Qur’an and the law. Yet my heart longed for the open road, for places I had only read about in the books of travelers before me. At the age of twenty-one, I set out on pilgrimage to Mecca, not knowing it would be the beginning of a lifetime’s journey.

The Pilgrimage That Never Ended

What was meant to be a journey of a year became a voyage across the known world. I crossed deserts and sailed oceans, traveling through North Africa, the Middle East, East Africa, and beyond. I studied in the great cities of Cairo and Damascus, prayed in the holy mosques of Mecca and Medina, and sat at the feet of scholars in far-off lands. My curiosity drove me onward, each new place opening the door to another adventure.

Across the Sands to Mali

In the year 1352, I turned my eyes toward the distant empire of Mali, drawn by stories of its wealth and the greatness of the Niger River. I joined a caravan across the Sahara, enduring the searing heat, the shifting sands, and the endless horizon. Weeks later, we reached the empire’s borders, and I beheld a land rich in gold, grain, and cattle.

Life Along the Niger River

I visited the city of Timbuktu and the capital of Mali, where the Niger River’s waters nourished fertile fields and thriving markets. I saw fishermen casting nets from slender canoes, traders exchanging salt for gold, and griots reciting the histories of kings. The people were devout in their faith, yet they also honored the customs of their ancestors, blending traditions in a way unlike any I had seen before.

Lessons from the Journey

I learned that the greatness of the Niger River was not only in its waters but in the life it sustained. Empires rose and fell along its banks, yet the river flowed on, binding people together through trade, travel, and shared memory. My time in Mali left me humbled by the generosity of its rulers and the resilience of its people.

The Final Roads

After thirty years of travel and tens of thousands of miles, I returned to Morocco, my beard grayed and my mind full of stories. I dictated my travels to a scholar, so that future generations could see the world through my eyes. My journeys taught me that every land holds wisdom for those willing to seek it, and that the road itself can be the greatest teacher of all.

River’s Bounty: Agriculture and Fishing Along the Niger – Told by Battuta

When I arrived in the lands of the Niger, I was struck by how deeply the river shaped the lives of its people. Its waters did not merely pass through their fields and villages—they breathed life into them. I had traveled through deserts where every drop of water was guarded as treasure, and so the abundance of the Niger seemed like a gift beyond measure. Here, the river’s yearly flooding turned the land into a vast green plain, and I could see why so many communities had chosen to settle along its banks.

Fields Rich with Grain

In the villages and towns I passed, the fields stretched far and wide, thick with millet, rice, and sorghum. Farmers worked in the soft soil left behind by the retreating floods, their hands planting seeds in neat rows. Women and men labored side by side, using simple but effective tools, while children carried water in clay pots to tend young plants. I saw clever irrigation channels guiding the river’s flow into the fields, allowing crops to grow even after the floods had withdrawn. The harvests filled great granaries, ensuring that food was plentiful not only for the farmers but for the merchants and travelers who passed through.

The Work of the Fishermen

On the river itself, I saw the work of the Bozo people, masters of fishing. Their narrow canoes seemed to glide effortlessly over the water, guided by long poles or paddles. They cast wide nets woven from plant fibers, sometimes alone, sometimes in teams that spanned the river with a barrier of netting. I watched them spear fish in the shallows, their eyes trained to catch the slightest movement beneath the surface. The fish were dried in the sun or smoked over small fires, ready to be stored for months or traded in the markets.

Sustaining Great Populations

It became clear to me that the wealth of the Niger was not in gold alone, but in its ability to feed so many. Cities like Gao and Djenné could grow large and bustling because they were supplied by this constant flow of grain and fish. The merchants on their journeys knew they could stop along the river to find fresh food, and the farmers knew they could sell their surplus to passing caravans. It was this dependable abundance that allowed towns to grow into cities and kingdoms to endure.

A Lesson from the River

In my travels, I learned that a strong city is not built on walls alone but on the steady provision of life’s needs. Along the Niger, the fields and waters worked together to provide those needs. It was a harmony between land, water, and people, each giving to the other. I left with the memory of green fields swaying in the wind and the sight of fishermen bringing in their catch at sunset—a reminder that the true foundation of a civilization is the work that feeds it.

The River as a Prize: Conflicts Between River Kingdoms – Told by Za Alayaman

I am Za Alayaman, and I learned quickly that the Niger is both a blessing and a burden. Its fertile banks feed the people, its waters carry trade, and its crossings link distant lands. Yet because it gives so much, many seek to claim it for themselves. In my time, the river was not ruled by a single hand, but by many kingdoms, each guarding its share. Between them lay alliances, rivalries, and the constant tension of knowing that one year’s friend could be the next year’s foe.

The Struggle for the Floodplains

The inland delta, with its rich soil and endless fish, was the most coveted land of all. Farmers planted millet and rice in the silt left by the floods, while herders brought their cattle to graze on the grasses. Control over this region meant not only wealth but the power to feed armies and supply markets. Gao’s own warriors often had to defend our claim against neighboring peoples who believed their need was greater than ours. These disputes could begin with words but often ended with spears.

Fishing Zones and River Rights

The Bozo people, masters of the river, controlled many of the best fishing grounds. They guarded their waters fiercely, and rightly so, for fish were as important as grain in feeding the cities. Disagreements arose when rival kingdoms tried to fish beyond their agreed boundaries. Sometimes these quarrels were settled by negotiation or tribute, but at other times they sparked raids, with canoes clashing midstream and nets torn in anger.

The Battle for the Crossings

Trade could not flow without safe passage across the Niger. Fords, ferries, and narrow bends where bridges could be built became points of great contention. Whoever held these crossings could tax merchants, delay caravans, or close routes entirely during war. Gao itself fought more than once to secure a key crossing against our eastern rivals, for without it, we risked losing our place as a hub between the river and the desert.

Rivalries with Neighboring States

In my time, Gao’s most persistent rivals were kingdoms to the west and south, whose own ambitions matched ours. The disputes were rarely about distant lands—they were almost always over the river itself, its food, and its trade. Warfare was swift and often seasonal, beginning after the harvest and ending before the floods returned. Yet even in conflict, there were rules: markets might be spared, emissaries allowed to cross, and envoys sent to negotiate peace once both sides had shown their strength.

Lessons from the River Wars

I came to see that the Niger cannot be truly owned. It passes through many lands, feeding and enriching all who live along it. Those who try to claim it entirely will find themselves in constant war, while those who learn to share its flow will know lasting prosperity. In my reign, we fought when we had to, but we also built alliances that allowed traders, farmers, and fishermen to work side by side. It was not peace without tension, but it kept the river’s lifeblood moving for all.

My Name is Sundiata Keita (c. 1217–1255): Founder of the Mali Empire

I was born in the Mandé heartland around the year 1217, a time when our people were fractured among small kingdoms. My mother, Sogolon, was not of royal beauty, and because of my crippled legs in childhood, many doubted I would ever rule. I could not walk until I was seven years old, and whispers filled the court that I was cursed. Yet my spirit was strong, and I listened closely to the elders’ tales, learning patience and wisdom even as I was mocked.

The Journey to Strength

When my father died, my family’s enemies drove us from the court. We wandered in exile, living under the kindness of other rulers. During these years, I learned the ways of different lands, the skills of the hunt, the strategies of war, and the importance of uniting people through shared purpose. My legs grew strong, and so did my resolve.

The Call to Leadership

News reached me that the sorcerer-king Soumaoro Kanté had seized much of the Mandé lands. My people sent messengers, asking me to return and lead them. I could not ignore their plea. I gathered allies from far and wide—hunters, warriors, and kings who feared Soumaoro’s cruelty. We formed an army unlike any seen before along the Niger.

The Battle of Kirina

In 1235, we met Soumaoro’s forces at Kirina. His magic was feared, but I knew courage and unity could overcome it. Our forces struck with precision, breaking his power and freeing the Mandé from his grasp. This victory was the birth of the Mali Empire, and I was named mansa—emperor—by the will of my people.

Building the Mali Empire

My reign brought peace to a region that had long known war. I strengthened trade along the Niger River, linking gold mines in the south to markets in the north. I established laws that respected local customs, and I ensured that griots, our keepers of history, would preserve our stories for generations. Cities like Niani became centers of culture and learning, drawing merchants and scholars from across Africa.

My Legacy

When I passed from this world, the Mali Empire stood as one of the richest and most respected realms of its time. My life began in weakness but ended in strength, a journey that taught me the power of patience, unity, and vision. The Niger River still carries the lifeblood of our people, just as it did in my day, and the stories of Sundiata continue to remind them that greatness can rise from the humblest beginnings.

Trans-Saharan Trade and the Niger River’s Role – Sundiata Keita

When I rose to rule, I saw the Niger River not only as the heart of my people but as the bridge to lands far beyond our horizon. Its waters carried canoes from the forests and farmlands, bringing grain, fish, and goods to the cities along its banks. But the river’s true power came when it met the desert’s caravan routes, for together they formed the veins through which the lifeblood of our empire flowed.

The Gold of the South

In the forests and mines to the south, our people drew gold from the earth. This gold traveled northward along the river in boats carved from great logs, guarded by warriors loyal to the crown. At the cities of the Niger bend, the gold met the camel caravans from the Sahara, ready to be traded for the desert’s treasures. It was this meeting of river and sand that made Mali a name known across continents.

The Salt of the North

From the heart of the desert came salt, cut from the great mines of Taghaza and carried on the backs of camels. To those who live in lands of plenty, salt may seem small, but in the heat of our country, it is as precious as gold. The caravans brought these slabs to the river towns, where they were loaded into boats and taken to markets deep in the south. In this way, salt and gold crossed paths, each enriching the other’s journey.

Expansion of Markets

By securing the routes along the Niger and protecting the caravans through the desert, I ensured that our markets grew in both size and reach. Merchants from distant lands came to Timbuktu, Gao, and Djenné to trade not only gold and salt but ivory, cloth, copper, and books of learning. Each city became a meeting place of cultures, where the tongues of many peoples could be heard in the same marketplace.

The Empire’s Prosperity

The wealth from this trade filled our treasuries and strengthened our armies. It built mosques and schools, supported scholars, and fed the poor. Yet it was not wealth alone that mattered—it was the flow of knowledge, ideas, and customs that came with the goods. The Niger River carried more than cargo; it carried the spirit of exchange that bound our empire to the wider world.

A Legacy of Connection

When I think of my reign, I remember not only the battles won but the trade routes secured. The Niger and the Sahara, so different in nature, worked together to bring prosperity to our people. Long after my time, as caravans still cross the desert and boats still ply the river, that partnership remains the foundation of Mali’s greatness.

My Name is Griot Mamadou Kouyaté (fictional figure): Holder of Memories

I was born around the year 1533 in the city-state of Zazzau, one of the great Hausa kingdoms of the Sahel. My father, King Nikatau, ruled over a land of bustling markets and high earthen walls. From the moment I could walk, I was drawn to the clang of steel and the thrill of the hunt. While other girls were expected to master the domestic arts, I learned to wield the spear and ride into the savanna.

The Making of a Warrior

Under my brother’s reign, I served as a military commander, leading cavalry into battle. We fought to defend our lands, secure our trade routes, and bring more towns under the influence of Zazzau. My skill in war became known across the Hausa states, and soon my name carried both fear and respect.

Ascending the Throne

When my brother died, I took the throne as queen. In our tradition, a woman ruling in her own right was rare, but my victories had already proven my worth. I ruled not from the safety of the palace but from horseback, dressed in armor, at the head of my warriors. I expanded Zazzau’s territory to its greatest reach, securing control over key trade routes connected to the Niger River and beyond.

Building an Empire

My conquests were not for glory alone. Each victory brought wealth to my people—taxes from caravans, tribute from allies, and access to goods from across the Sahara. I ordered the building of fortified walls around cities, strengthening our defenses and showing the might of Zazzau. These walls, known as ganuwar Amina, stood for generations.

The Role of Trade

I understood that power was more than swords. The caravans that passed through our lands carried salt, gold, cloth, and slaves, linking us to the Niger River basin and the far-off ports of the Mediterranean. I ensured that Zazzau’s markets thrived, drawing merchants from every corner of the region.

Legacy of a Warrior Queen

When I died around 1610, the lands I had united stretched farther than any ruler of Zazzau before me. My life was forged in the saddle, my reign built on courage and strategy. The tales of my campaigns are still told, not just as stories of war, but as proof that leadership knows no bounds of gender, and that a single determined heart can change the fate of a nation.

Born to Carry the Stories: Cultural Diversity Along the Niger – Told by Kouyaté

I am Mamadou Kouyaté, born to the noble calling of the griots, the keepers of our people’s history. My father’s kora was the first sound I remember, its strings singing the tales of kings and warriors, farmers and fishermen, traders and travelers. I was raised along the banks of the Niger, where the river flows through many lands and cultures, each with its own tongue, customs, and songs. My duty was to know them all, for the story of one is never complete without the others.

The Songhai by the Great Bend

In Gao and the lands around the great bend of the Niger, I learned the stories of the Songhai. They were masters of the river, their canoes swift and their markets filled with goods from far away. The Songhai valued both warriors and traders, building cities where the wealth of the desert and the river met. Their rulers dreamed not only of defending their land but of controlling the lifeblood of trade itself.

The Mandé of the Heartland

Traveling westward, I walked among the Mandé people, whose kingdoms were born from the uniting of many clans. They were skilled farmers and traders, growing millet and rice in the fertile floodplains. The Mandé were also builders of empires, from the early lands of Wagadu to the mighty Mali. Their griots, my brothers and sisters in the art of memory, taught me the great epics—tales of Sundiata Keita, who bound many peoples into one.

The Fulani of the Open Grasslands

To the north and across the Sahel, I met the Fulani, herders who guided their cattle across wide plains. Their lives followed the rains, and their movements carried stories, songs, and customs from one region to another. Some settled in towns along the Niger, blending their ways with the farmers and traders they met. In their music, I heard the echo of far journeys; in their wisdom, the patience of those who follow the seasons.

The Hausa and the Cities of the Trade Routes

Eastward, the Hausa built great walled cities like Kano and Zaria, tied to the Niger by the trade routes that crossed the savanna. Their markets brimmed with fine cloth, leatherwork, and metal goods. The Hausa were known for their skill in governance and their ability to weave together diverse peoples into thriving city-states. Even those far from the Niger itself felt its reach through the flow of goods and ideas.

The Weaving of Many Threads

Along the river’s banks and in the caravan paths that touched it, these peoples met, traded, and sometimes fought. Yet from their meeting came more than goods—it brought new languages, music, foods, and beliefs. A Mandé merchant might wear Hausa leather, a Songhai warrior might ride with Fulani herders, and a Hausa trader might sell Mandé rice in a market far to the east. The Niger was not just a river; it was a loom, weaving the threads of many cultures into a shared cloth.

Carrying the River’s Voice

As a griot, I carry the songs of all these peoples. I tell their victories and defeats, their joys and sorrows, so that none may forget how the Niger bound them together. In its waters, you can hear the mingling of many voices. To know the Niger is to know that its strength lies in its diversity, and that the stories of its peoples are like its currents—flowing together toward the same endless sea.

The Call of the Griot: Art, Music, and Oral Tradition – Told by Kouyaté

I was born to the Kouyaté line, a family whose name has echoed in the courts and marketplaces of the Niger River lands for generations. From my earliest days, I was taught that our voices are not our own—they belong to the people, to the history that flows through them. My first lessons were not in books, but in the songs, proverbs, and tales passed from father to son, mother to daughter. To be a griot is to be a bridge between past and present, a living archive of the river’s memory.

The Power of Storytelling

When I stand before a gathering, kora in hand, I do not speak merely to entertain. I weave the deeds of kings, the struggles of warriors, the wisdom of elders, and the humor of common folk into a single tapestry. The Epic of Sundiata, the founding of Gao, the journeys of the Bozo fishermen—these are not distant tales but living truths. A well-told story can inspire a warrior, guide a ruler, or remind a child of their place in the great chain of their people.

The Drum’s Heartbeat

No griot stands alone. Behind my voice are the drummers, whose rhythms give breath to the words. The djembe speaks in tones that mimic the human voice, carrying messages across the marketplace or summoning crowds to listen. The talking drum, when struck and squeezed, can imitate the rise and fall of our speech, allowing messages to travel faster than a runner. These rhythms are not mere music—they are a language of their own, known to those who grew up in its sound.

Symbols in Clay and Cloth

Art along the Niger is not silent. The mud-brick walls of Djenné are shaped by hands that remember the old designs, each pattern telling something of the family within. Cloth is dyed in deep blues with indigo, and the patterns speak of lineage, profession, or a moment in history. Even the calabash bowls used in daily life may bear carvings of fish, waves, and birds, symbols of the river’s gift and the stories it carries.

The River as Inspiration

The Niger is in all of our art and music. Its seasonal floods inspire songs of renewal, its dangers give rise to cautionary tales, and its bounty is praised in harvest celebrations. The fishermen sing as they cast their nets, the farmers chant as they plant their seeds, and the women hum as they weave cloth. To live along the Niger is to have its rhythm in your very blood.

Carrying the Legacy Forward

As a griot, my duty is not only to preserve these traditions but to pass them on. I teach the young to remember that a story poorly told is a history half-lost, and a drum played without heart cannot move the soul. In every tale, rhythm, and design, we honor those who came before and guide those yet to come. So long as the Niger flows, its art, music, and stories will endure, carried in the voices of those like me.

Pre-Islamic Faith Along the Niger: Religion and Belief Systems – Told by Kouyaté

The Old Ways Before the New Faith

I have sung the stories of our people long before the muezzin’s call to prayer echoed across the river. Before the holy words of Islam reached these lands, our ancestors followed the ways taught by the earth, the sky, and the waters. Their gods and spirits were not distant; they lived in the river’s current, in the trees’ shade, and in the voices of those who came before. These beliefs were not merely personal—they bound whole communities together, guiding how they farmed, fished, married, and settled disputes.

The Strength of Ancestor Worship

Our people have always honored those who came before us. Ancestors were not thought gone when they left this world—they were still part of the family, watching, guiding, and protecting. Elders told the young of the deeds and wisdom of their lineage, and offerings were made to seek blessings for the harvest or safety in travel. In many villages, the clan’s history was not just a memory—it was a living force that shaped decisions, for to dishonor the ancestors was to risk the community’s very harmony.

The Spirits of the Land and Sky

Animism, the belief that all things have a spirit, was the heartbeat of daily life. The baobab tree that shaded the village was more than wood and leaves—it was a guardian. The rocks along the river bend, the hills rising above the plains, and the winds that swept across the grasslands each carried their own power. Hunters would speak to the spirit of the animal before the hunt, asking for balance between taking life and sustaining life. Every path and every field was shared with the unseen.

The Deities of the River

The Niger itself was seen as alive, a mother and provider. Among the Bozo and other river peoples, there were tales of water spirits—some gentle, some fierce—who guarded the fish and controlled the floods. Fishermen left small offerings on the banks before casting their nets, and boat-builders asked the river’s blessing before their craft first touched the water. The cycles of flood and retreat were not only natural events—they were sacred ceremonies, marking the turning of the year.

Community Shaped by Faith

These beliefs did more than guide the spirit—they organized the people. Priests, diviners, and elders held authority, interpreting signs from the ancestors or the land. Festivals tied to planting, harvest, and the river’s rise brought everyone together, reinforcing bonds between families and clans. Disputes were settled with the counsel of those who could read the will of the spirits, ensuring that peace was maintained not just through law, but through harmony with the unseen world.

The Coming of Change

When Islam arrived with the caravans and merchants, it did not sweep these old ways aside all at once. For many, the new faith was woven into the fabric of the old. Even now, echoes of ancestor reverence, nature’s spirits, and the river’s deities live alongside the call to prayer. The Niger remembers both the prayers whispered in Arabic and the chants sung in the ancient tongues, and so do I, as long as my voice can carry them.

How Islam Took Over the Markets, Faith, and Culture: Told by Battuta

When I set foot in the empire of Mali, Islam was already strong in its cities. The muezzin’s call to prayer rang over markets, and rulers were advised by qadis trained in the law of the Qur’an. Yet the faith had not always been here. The elders told me that its path into the Niger River lands was not carved by armies but carried by merchants. From the markets of Sijilmasa and Tunis, caravans crossed the Sahara with salt, copper, and cloth, bringing with them the words of the Prophet. At first, Islam was a faith of travelers and traders, foreign to the people of the river, but it would soon find a place at the heart of their lives.

The Power of the Market

I saw with my own eyes how the markets themselves became the first mosques of the merchants. Those who came from North Africa and beyond insisted on doing business in a manner guided by their faith—contracts sworn by the Qur’an, disputes judged by Islamic law, and business conducted around the hours of prayer. If a local trader wished to deal with these merchants, he found it easier to adopt their customs than to resist them. The more the river towns grew rich on this trade, the more their leaders saw the advantage of welcoming Islam into their public life.

The Influence of the Rulers

It was the kings and chiefs who gave Islam its strongest foothold. By embracing the faith, they gained the trust and respect of the North African merchants, opening their cities to greater trade and wealth. They sent their sons to learn Arabic and study the Qur’an, for knowledge was a form of power as valuable as gold. Soon, the presence of scholars, judges, and mosque builders made the faith not an outsider’s belief but a mark of prestige for the ruling class.

The Pressure of Prestige

The people of the river were not forced into Islam by the sword, but they felt the weight of expectation. To refuse the customs of the merchants was to risk losing their trade, and they were the only traders since they took over the Egypt and the land routes in and out of Africa. Also, to resist the king’s chosen faith was to stand apart from the growing order of the cities. The pressure was subtle, woven into the daily exchanges of goods, the laws of the market, and the language of the court. Those who accepted Islam found doors opened to them; those who did not found those same doors slowly closing.

The Shaping of Culture

Over time, the faith became part of the very fabric of life. Market days were timed to avoid clashing with Friday prayers. Festivals began to mix the old traditions with Qur’anic recitations. Arabic words entered the local tongues, shaping how people spoke about trade, justice, and morality. Islam brought its own architecture, its own system of law, its own ways of marking the year. And in adopting it, the Niger River peoples reshaped it in turn, blending the new with the old.

Conquest Without the Sword

As I traveled, I saw that Islam’s triumph here was not through armies but through influence, opportunity, and the quiet pull of belonging. The merchants who brought their goods also brought their faith, and the rulers who sought wealth and alliance made it their own. By the time I walked the streets of Gao and Timbuktu, the old beliefs still lived in the villages, but the heart of the cities beat to the rhythm of the prayer drum. It was a conquest of the mind and the market, not of blood and fire.

A Land Worth Defending: Military Conflicts Along the Niger – Told by Keita

When I became mansa, I inherited not only the lands of my ancestors but also the responsibility to protect the lifelines of our empire. The Niger River was more than a body of water—it was the road upon which our wealth traveled, carrying grain, gold, salt, and people between our cities. The trade routes that crossed the river were the veins of our prosperity, and without defense, they would be choked by bandits, rival kingdoms, and those who sought to control our lifeblood.

Threats from Every Direction

Our enemies came in many forms. To the north, desert raiders sought to plunder caravans before they reached the safety of our markets. Along the river, rival chieftains sometimes tried to seize control of key crossings, demanding tribute from passing merchants. In times of drought or scarcity, even neighboring peoples could become desperate enough to raid the river towns. I knew that if the Niger was not secure, the unity I had forged would begin to unravel.

Defending the River Crossings

I ordered the construction and fortification of watchposts at key fords and ferries, placing trusted warriors under the command of loyal captains. These strongpoints ensured that anyone wishing to cross the Niger within my lands was known, taxed, and, if necessary, turned away. Patrols in swift canoes kept the river itself safe, responding quickly to trouble and guarding the boats that carried goods between cities.

Securing the Trade Routes

Our caravans, carrying gold to the north and returning with salt, copper, and cloth, were escorted by armed guards. I forged alliances with the desert tribes whose lands they passed through, granting them favorable trade in exchange for protection along the road. When talks failed, I sent my cavalry to make it clear that the empire would not tolerate threats to its lifelines.

Protecting the Urban Centers

Cities such as Niani, Timbuktu, and Gao were fortified with walls of earth and stone, designed to hold back both enemy armies and sudden raids. In times of war, these cities could shelter merchants and their goods, ensuring that the economy of the empire did not collapse under siege. Markets were kept open under watch, so trade could continue even in uncertain times.

The Balance of Strength and Peace

My goal was never endless war, but lasting stability. By showing our strength, we discouraged many enemies from acting, and by securing our borders, we gave traders and farmers the confidence to invest in their work. The Niger River and the routes that fed it became known as safe passages, drawing more merchants and travelers into our lands.

A Legacy of Security

When I look back on my reign, I know that unity alone would not have held our empire together without security. The Niger’s waters still flow, and its crossings are still guarded because of the foundations we laid. In my time, we proved that an empire’s strength is measured not only by its size, but by its ability to protect the paths on which its life depends.

A City Older Than Our Reigns: Early Urbanization and the Mystery of Djenné-Djenno – By Za Alayman and Keita

Za Alayaman: Long before my arrival at the Niger bend, before the Songhai and before the Mali Empire, there was Djenné-Djenno. It rose from the inland delta around 250 years before the birth of Christ, when the world was different and yet the river’s waters flowed as they do now. It was already ancient when I came to West Africa, a city built not of stone walls and kings’ palaces, but of clay mounds and bustling marketplaces.

Sundiata Keita: By my time, Djenné-Djenno’s name lived more in memory than in power, yet its legacy still shaped the region. It was a place where people from many lands came together, and where trade routes were mapped out long before either of our reigns. Understanding its story is like reading the first chapters of the river’s history.

The Rise of a Trading Power

Za Alayaman: Its location in the inland delta was no accident. The floods of the Niger enriched the soil for farming, the waterways fed fishing, and the city sat at the crossroads of routes linking the forest belt in the south to the Sahara in the north. Archaeologists in your time would find beads from far-off lands, copper ornaments, and glassware—proof that Djenné-Djenno was part of a vast network, centuries before the camel caravans we know became common.

Sundiata Keita: And yet it was not simply a place of goods—it was a place of ideas. Techniques for ironworking spread from there, as did farming methods suited to the floodplains. When later cities like Djenné and Timbuktu grew in my time, they drew on the foundations laid by Djenné-Djenno’s merchants and craftsmen.

The Question of Leadership

Za Alayaman: Here lies one of its mysteries. Some say Djenné-Djenno was ruled by kings or chiefs, others believe it was a loose collection of neighborhoods, each governed by its own elders. The lack of royal tombs or palaces in its ruins has led some to think its power came from the market rather than the throne.

Sundiata Keita: In my experience, a city can thrive without a single ruler if trade is strong and the people trust the systems they share. Perhaps Djenné-Djenno’s strength was in this—shared governance among traders, farmers, and fishers who each had a voice in their city’s direction. But such a system can also be fragile, especially when threatened by outside powers.

The Decline of a Giant

Za Alayaman: By the time I ruled in Gao, Djenné-Djenno had begun to fade. Shifts in trade routes may have drawn merchants elsewhere, perhaps toward Gao itself or to the growing settlements along the desert’s edge. Climate change, flooding patterns, or disease may have driven people to abandon parts of the city.

Sundiata Keita: And in my reign, newer cities like Djenné rose nearby, taking the name but building on a different model—more centralized, more tied to imperial power. The old Djenné-Djenno was left behind, its mounds slowly reclaimed by the earth, even as its influence lived on in the cities that followed.

Lessons from the Past

Za Alayaman: Djenné-Djenno shows us that urban life along the Niger did not begin with our empires—it is as old as the great river’s floods. Its mystery is a reminder that history is not always written in stone; sometimes it is shaped in clay and carried away by the waters.

Sundiata Keita: And it teaches that trade, ideas, and cooperation can build a city as surely as walls and armies. We may never know all its secrets, but we walk in the paths it first cleared, and the Niger still carries its story to those who will listen.

Cities Rising from the Riverbanks: Architecture and Urban Planning – Sundiata Keita

When I united the lands of the Niger, I found towns and villages already shaped by the river’s gifts. Yet to bind them into a true empire, we needed cities that reflected both our strength and our culture. The river was our artery, and along its banks we built places where trade, worship, and governance could flourish side by side. Each city became a reflection of the people who lived there, their skills, and their vision for the future.

The Craft of Mud-Brick Building

The earth of the Niger’s floodplains gave us the perfect material for construction. From this clay-rich soil, our builders shaped sun-dried mud bricks, strong enough to stand for generations and cool in the heat of the day. Layer by layer, these bricks formed walls thick and high, able to resist both the sun and the rains. The skill of our masons turned these humble materials into grand forms—mosques with soaring facades, palaces fit for kings, and sturdy homes for merchants and craftsmen.

Mosques as the Heart of Faith and Learning

In each major city, the mosque stood not only as a place of prayer but as a center of learning. Built in the style of our land, with wooden beams jutting from the walls for both beauty and maintenance, they became symbols of our connection to the wider Muslim world. Here, scholars taught the Qur’an, law, and languages, and students gathered from across the empire. These mosques were more than buildings—they were pillars of knowledge and unity.

The Life of the Marketplaces

Our cities were shaped around their markets, for trade was the lifeblood of the Niger. Open squares bustled with merchants selling grain, fish, salt, gold, cloth, and tools. Covered stalls offered shade from the sun, while storage buildings protected goods waiting for caravans or riverboats. Streets were planned to guide traffic between market, mosque, and the riverfront, ensuring that commerce flowed as smoothly as the water nearby.

The Structure of Ancient River Cities

In the design of our cities, the river was always the anchor. The docks lay at the heart of activity, feeding goods into warehouses and markets. Residential quarters surrounded the center, often arranged by profession or clan. Administrative buildings and the palace stood close to the markets, where the rulers could oversee trade and resolve disputes. Walls encircled the cities, protecting them from raiders and marking the boundary between the bustle within and the farmlands beyond.

A Living Vision

By shaping our cities with intention, we built more than walls and streets—we built communities where faith, trade, and governance could thrive together. The architecture of the Niger’s cities told the story of a people who worked with the gifts of the river and the land, creating beauty and order from simple materials. Long after my time, these cities will stand as proof that strength is not only in armies, but in the places we build for our people to live, work, and dream.

The River’s Memory: Legacy of the Niger River Culture Today – Told by Kouyaté

I am Mamadou Kouyaté, griot of the Niger, and I tell you this: the river remembers. It remembers the paddles of the Bozo fishermen, the chants of the Mandé warriors, the prayers from the mosque at Gao, and the drumbeats of the Hausa traders. Though centuries have passed since the days of great empires, the Niger’s song still flows through the lands it touches, and its story is still written in the lives of the people today.

Traditions That Endure

The tales I carry are not relics for the past alone. In villages and cities along the river, griots still recite the epics of Sundiata, the deeds of Askia, and the wisdom of the elders. Farmers still plant with the rhythm of the floods, and fishermen still follow the same channels their ancestors knew. Music, with the kora, balafon, and drums, still fills the air in festivals and markets, binding communities together just as it did long ago.

Trade Routes Reborn

The caravans of camels have given way to trucks and riverboats, but the paths they follow are often the same. Goods still travel from the coast to the Sahel, from the farmlands to the desert, echoing the flow of gold, salt, and grain that once made cities like Timbuktu and Djenné thrive. Markets along the Niger remain hubs where languages mix, deals are struck, and strangers leave as friends.

The Influence of Many Peoples

The river’s basin is still home to the Songhai, Mandé, Fulani, Hausa, and many others. Their cultures blend in food, language, and craft. A dish on the table may hold spices from far-off lands, rice from the floodplains, and fish from the river’s bend. Cloth may be woven with designs that speak both of ancient kingdoms and modern pride. Each group brings its own thread to the tapestry, and together they keep the weave strong.

The River as Teacher

The Niger has always taught that survival depends on cooperation. In the past, kingdoms rose when they protected the river and shared in its bounty. Today, nations still depend on its waters for farming, trade, and connection. But they must also work together to keep it clean, to guard against floods and droughts, and to ensure its life flows for generations to come.

The Griot’s Promise

As long as I live, I will carry the voices of the river’s past into the present. I will remind the young that the ground beneath them was shaped by centuries of trade and tradition, that the music they dance to carries the heartbeat of their ancestors, and that the Niger is more than a river—it is the thread that binds the people of West Africa together. In its waters, the past and present meet, and its story will flow on, long after I am gone.

Two Rulers, Two Eras: Unification of the Niger Cultures and Transition to the Mali Empire – By Alayaman and Keita

I am Za Alayaman, first of the Za dynasty in Gao, and beside me stands Sundiata Keita, founder of the Mali Empire. We speak from different centuries, yet our stories meet on the waters of the Niger. In my time, the river’s peoples were many—Songhai, Bozo, Mandé, Fulani, and others—each guarding their own lands and ways. By Sundiata’s time, these same peoples had begun to imagine themselves as part of something greater, bound by shared trade, faith, and destiny.

Laying the Foundations

Za Alayaman: When I came from Yemen to the bend of the Niger, I found a land rich in trade but divided in rule. My work was to unite the clans of Gao and give them a leader who could protect both the river and the caravan paths. By securing the trade routes, encouraging markets, and forging alliances with river peoples, I planted the seeds of unity, though they would take centuries to grow. The Niger taught me that power comes not from conquering every shore, but from ensuring all can benefit from its flow.

Sundiata Keita: Your foundations reached far beyond Gao, Alayaman. By my day, the Niger’s peoples were linked by trade and travel, but they were still threatened by rival powers. Soumaoro Kanté of Sosso sought to bind them under his tyranny. My task was not only to defeat him but to unite these diverse cultures into a single realm, strong enough to keep the river free.

The Meeting of Cultures

Za Alayaman: In my era, the river was a crossroads. The Songhai brought fish and grain, the Bozo carried goods in their canoes, and traders from the desert brought salt and copper. Each people guarded its customs, but markets and marriages slowly wove them together. My role was to protect these connections, so no one tribe could cut them.

Sundiata Keita: By my reign, this weaving had grown into a strong cloth, yet it needed a common banner. In bringing the Mandé, Songhai, and others into the Mali Empire, I did not strip away their ways. Instead, I built a system where each culture kept its own traditions, but shared in the protection of our armies, the fairness of our laws, and the prosperity of our markets.

From River Kingdoms to Empire

Za Alayaman: I ruled in a time when unity was fragile, dependent on trade and diplomacy. My dynasty kept Gao strong, but the river’s vast length meant no one kingdom could hold it all.

Sundiata Keita: When I united the lands from the forests to the desert, I made the Niger the spine of our empire. Cities like Timbuktu, Gao, and Djenné became linked not just by trade, but by loyalty to the empire’s stability. What began in your day as scattered partnerships became, in mine, a single political force stretching across West Africa.

The Legacy of the Niger

Za Alayaman: The unification you achieved was the flowering of seeds planted in many earlier seasons.

Sundiata Keita: And your work reminds us that an empire is not born in a single victory—it is shaped by generations who protect the river’s life. Today, the Niger still carries the voices of our peoples, joined by its waters long before they were joined by a crown.

Comments