2. Heroes and Villains of Ancient Africa: The Mesolithic Era (c. 10,000 BC – c. 8,000 BC)

- Historical Conquest Team

- Aug 6, 2025

- 47 min read

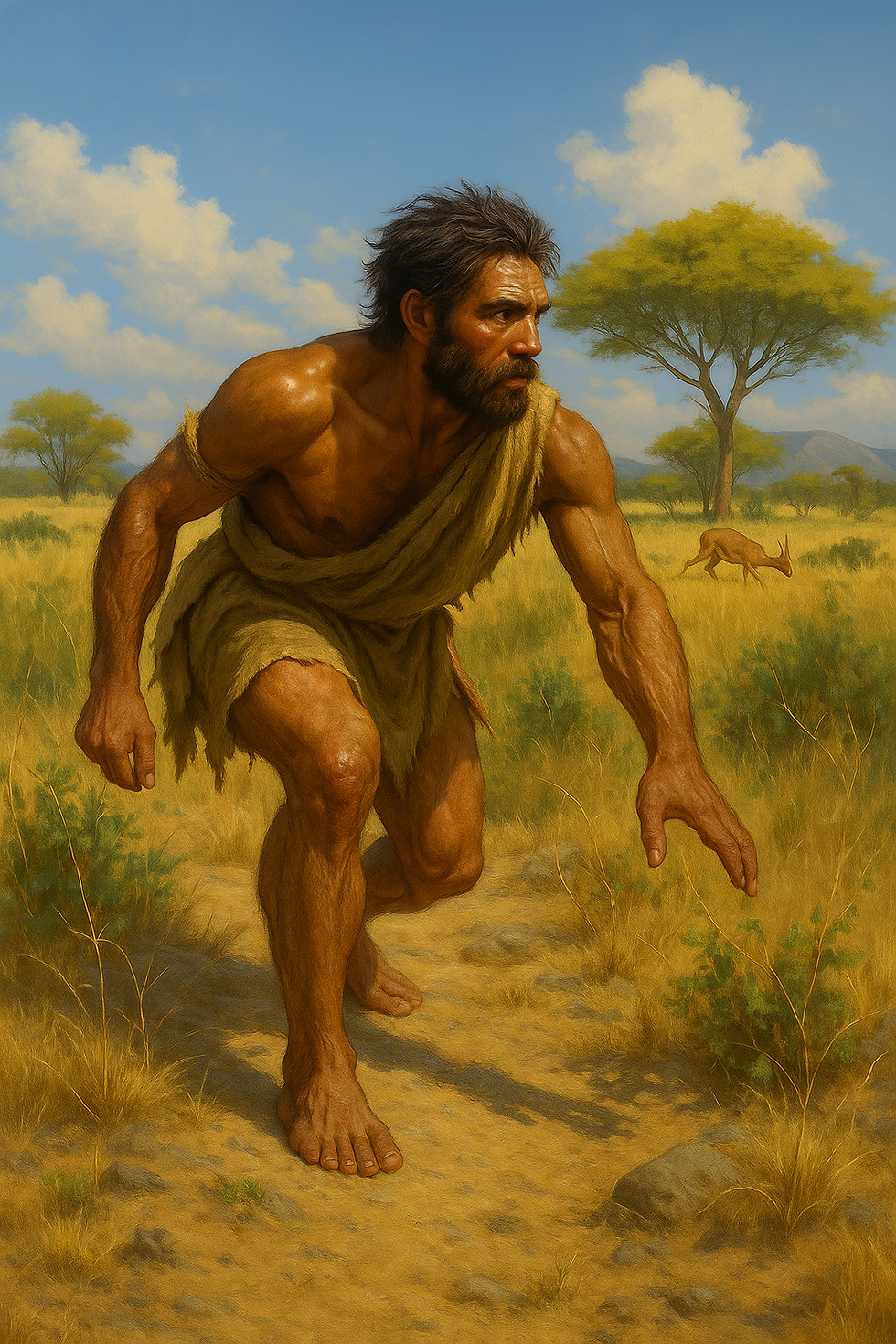

My Name is Kael the Hunter-Tracker: My Life Beneath the Forest Sky

I was born in the valley where the ice once ruled, a place carved by time and thaw. The elders said the glaciers had pulled back like great beasts retreating into sleep. Where there was once white silence, there was now green. Rivers rushed over stone, and forests crept forward, birthing deer trails and shelter for birds. I was born during the first warm season after the third moon, when the air smelled of damp bark and birch sap. My mother cradled me in a deerskin sling, and my father smeared red ochre on my brow, a mark for strength and sight.

Learning to Walk with the Beasts

As a child, I chased the prints of animals before I could speak their names. My father, Talak, was the clan’s finest tracker. He taught me to see the world not in shapes but in signs. A broken blade of grass meant a deer passed at dawn. A snapped twig told of a boar’s panic. The way birds flew, the direction of the wind, even the silence of the trees—these became my language. I learned to step softly, to breathe with the forest, and to still my heart before the throw of a spear. My eyes became sharper, my feet quicker, and my hands steady.

The Rite of the Red Stag

When my voice deepened and my shoulders grew broad, the time came to prove my path. For three days, I followed the trail of a great red stag deep into the northern groves where no fires burned. It led me through thorn and fog, across river and stone. I ate only what I caught—a trout, a squirrel, a handful of nuts. On the fourth dawn, I saw him. His antlers were heavy like branches, and his eyes met mine with calm defiance. I did not chase. I watched, waited, and listened to the wind. When the time came, I let the spear fly true. He fell with grace, as if offering himself. I knelt beside him and thanked his spirit, marking my cheeks with his blood.

The Seasons of Change

Years passed, and the land changed with me. New herds arrived—elk, wild cattle, strange horned creatures we hadn’t seen before. The waters grew full of fish, and the birds returned in greater number. But so too came floods and bitter winters. Sometimes we moved our camps to higher ground or closer to the lake. Sometimes, we returned to the old caves, where my grandfather once painted the beasts with ash and ochre. I learned to make traps from bent wood and sinew, to fish with barbed bone, and to walk farther, longer, sometimes trading furs with distant clans we once considered strangers.

Loss and the Silent Path

There was a year when the winter would not let go. Snow held fast into the time of planting, and many starved. My younger brother, Ralo, followed me into the hills to hunt but fell through the ice of the river. His death quieted me. I no longer sang around the fire. I spent long hours walking alone, listening to the ground. I began to understand things that had no words—the grief of a bird’s call, the wisdom in a wolf’s howl, the way the earth remembers every footstep. I began to see myself not as a hunter of beasts but as part of their circle.

The Bond with the Wild Ones

One morning, while tracking boar, I found a pup—small, fur matted, ribs sharp. A wolf, left behind. I could have left him. I should have. But something in his eyes, wide and wild, spoke of survival. I carried him back and named him Talu. As he grew, he became my shadow. We hunted together, slept together, spoke in glances. The others feared him at first, but they saw he was more than beast. He was clan. With Talu, I learned we could be more than predators—we could be partners with the world.

Now I Teach the Silence

I am no longer the fastest. My knees ache when the snow comes, and my eyes blur in the distance. But the young ones come to me now. I teach them the art of the still breath, the language of broken twigs, the stories carved in the mud. I tell them not just how to hunt, but how to know the land. To give thanks to the spirits. To track not with pride, but with humility. The world is always shifting, always speaking. It is not the spear that feeds us, but the ear that listens.

I Am of the Forest Sky

I was born beneath the meltwaters, and I will die beneath the forest sky. My blood is in the earth, in the bones of the deer, in the smoke of the fire. Let my story be carried by the wind, whispered in the rustle of the leaves, etched in the tracks we leave behind.

The Changing World After the Ice – Told by Kael the Hunter-Tracker

I was born just as the silence began to break. My grandfather told stories of a time when the land groaned beneath a sheet of ice, when the sun barely warmed the earth and the wind sliced through furs like sharpened stone. He remembered walking over frozen rivers that no longer exist, and seeing beasts so large they shook the ground with their passing. But I came into the world during the melt. The great ice was retreating, slipping back into the mountains and northern shadows. What was once white and still began to move and breathe again.

Where the Water Walked

As the ice receded, it left behind scars and gifts. Valleys carved by ancient pressure now became rivers, fast and full of life. Great lakes formed in depressions left by the glaciers’ weight, and marshes spread across the lowlands. Forests crept forward like cautious animals, claiming space inch by inch. Where there had been tundra and stone, there was now moss, fern, and young trees. Animals followed—deer, elk, wild boar. Birds returned in flocks so thick they darkened the sky. The land opened its hands and beckoned us to follow. So we did.

New Trails, New Prey

The paths we once knew were swallowed or changed. Old trails vanished beneath rising waters. Caves where we once slept were now filled with dripping pools. But new paths opened—dry ridges above the marshes, riverbanks lined with fish, wooded hills where herds gathered in the evening. I became a different kind of tracker. I no longer just followed the steps of animals—I followed the steps of the land itself as it changed. I learned to read the shape of the wind across tall grasses, the sound of frogs in flooded glades, the feel of mud that hinted at spring.

The Hunt Relearned

Our weapons changed as the world did. Spears meant for mammoths were too heavy for the quick deer of the forest. We began using smaller, sharper tips—microliths set into shafts like the teeth of a great jaw. Nets became tools of the hunt, not just the gather. Traps were crafted from bent wood and clever tension, hidden under leaves. We watched the behavior of fish and carved hooks from bone. The hunt was no longer just about strength—it became about patience, strategy, and listening. I taught the young ones that you do not chase prey anymore. You wait where the prey is going to be.

The Rise of the Dog

One of the greatest changes came on four legs. The wolves had always watched us from the edges of our fires. But in the changing world, some began to come closer. They followed us, ate our scraps, slept near our shelters. One night, I shared dried meat with a pup that had stayed behind when its pack moved on. He didn’t leave. He became my companion, then my partner in the hunt. Others followed. These creatures, once feared, now guarded our children and led us to prey. We did not tame them. We listened to them—and they listened back.

A Home That Keeps Moving

With the new abundance came questions. Some clans talked of staying in one place longer, of returning to the same camps each season. Anari noticed that certain plants came back where we had dropped seeds. Dagan spoke of dreams where the land asked us to rest. I did not trust it at first. I was raised in motion, in the rhythm of following the herds. But even I saw the wisdom in watching the land, not just chasing it. We built stronger shelters. We marked the return of the birds. We learned when to move—and when to stay.

The World Beneath My Feet

Now, when I walk the forest, I do not just track animals. I track time. The land is no longer the same as it was in my childhood, and it will not be the same for my children. The rivers cut new paths, the animals change their seasons, and the earth gives us signs if we know how to read them. I teach the young ones not to cling to what was, but to walk with what is becoming. The world melted not just to reveal new lands—but to show us a new way of living.

I Am the Tracker of Change

I am Kael, born in the melt, shaped by motion, carved by the edge of the changing world. The ice did not break us—it reshaped us. And in turn, we learned to reshape ourselves. My spear is lighter, my eyes sharper, my heart more patient. The old world cracked and softened, and from it, a new one was born. I walk it still, not as a conqueror, but as a listener, a learner, a hunter who follows not just beasts, but the footsteps of the earth itself.

My Name is Luma the Toolmaker-Innovator: My Life of Sparks and Shapes

I was born under the Watcher Star, the bright one that blinks even when the clouds press heavy on the night. My mother said my fingers never stopped moving, even as a baby. While other infants clutched for milk or warmth, I grabbed pebbles, bark, feathers—whatever caught the light. The elders used to laugh and say, “That one doesn’t play with toys. He makes them.” They were right. By the time I could walk, I was tying sticks together with sinew and prying apart beetles to see how their shells were shaped. Curiosity lived in me like fire beneath stone—hidden but always waiting to leap.

The First Break, The First Tool

My first real tool was born by accident. I dropped a piece of flint one morning and it shattered on a larger rock. One edge gleamed. I picked it up and felt how sharp it was. It sliced my palm, but I did not cry. I studied the cut, then studied the stone. I spent the rest of the day trying to do it again—break, twist, chip. My father thought I was wasting time, but my mother watched quietly. She brought me bones and antlers and taught me to boil sinew until it became thread. She knew. She saw the maker in me.

The Fire That Changed Everything

It was the night the storm hit. Lightning struck a tree not far from our camp, and the fire lit the sky like day. When the storm passed, the tree was still burning. Most feared it, but I went closer. I watched how it danced, how it hissed and cracked and turned green branches black. Then I noticed something strange—the stones near the fire looked different. Some had melted. Some had changed color. I stayed up all night feeding the fire with bits of shell and clay and rock, just to see what would happen. That was when I learned: fire is not just for warmth. Fire transforms.

Teaching the Edge

As I grew, others began to come to me. Hunters asked for sharper blades. Mothers wanted fishhooks that didn’t snap. Children begged for flutes made from reeds. I never turned them away. Every request was a puzzle. Every tool a story. I made axes with handles bent to the shape of the arm. I built nets with knots I learned from watching spiders. I created baskets sealed with pitch that could carry water. My favorite was the harpoon with two barbs that bent inward—once it struck, it would not slip free. That one helped Kael bring in his largest catch.

Mistakes and the River of Ash

Not every idea worked. Some were foolish. I once tried to make a cooking pot by sealing bark with sap. It exploded in the fire and sent sticky ash into the stew. Another time, I built a sling so powerful it knocked the user backward. But I never feared failure. Failure was the teacher that success bowed to. I learned to laugh at my own disasters. Sometimes, the clan laughed too. Sometimes, they got angry—especially when my “new way” slowed the old one. But over time, they saw what I saw: we were not just surviving. We were improving.

The Day We Stayed

It was Anari who said it first. She pointed to the grove near the river and said, “Look how the grains return where we scattered them.” I watched. I waited. And she was right. The plants came back, fuller, stronger. So I built a tool for digging—curved like a bird’s claw, with a wooden grip and a flint blade. It turned the soil faster than fingers ever could. Then I built a rack to dry seeds, a stone circle to mark the planting moon, and a fence to keep out the deer. Kael thought it was madness. Dagan said it was a vision. I only knew it worked. And that meant something new was beginning.

Passing the Flame

Now my fingers are not as quick. My eyes blur when the sun is high. But the young ones sit around me, flint in hand, asking, “How do you know where to strike?” I show them. Not with words, but with rhythm. Tap. Turn. Tap. Listen to the sound of the stone. Feel the song beneath your skin. I tell them that every object has a shape hiding inside it, and the maker’s job is only to set it free. Some laugh, thinking I speak in riddles. But some understand. And those are the ones who will carry the spark forward.

I Am the One Who Shapes

I am Luma, born with curious hands, son of no great warrior or leader, but father to many ideas. My name will not be painted on cave walls or carved into stone. But the tools I’ve made will outlast me. The bowls will feed. The axes will build. The flutes will sing. The seed diggers will turn the soil for those not yet born. That is enough. That is everything. My life has been a quiet flame—burning not for glory, but to light the way forward.

New Tools, New Skills – Told by Luma the Toolmaker-Innovator

From the first moment I opened my eyes to the world, I was surrounded by tools. My earliest memories are of firelight flickering on flint and bone, of the sharp click and crack as my mother shaped a scraper, her fingers calloused and sure. We lived in the shadows of the great stones—the heavy axes, the thick spearheads, the hammers of the old ways. These were the tools of the giants, passed down from the days when mammoths still walked the plains. But as I grew, I noticed something stirring in the hands of the younger ones. We began to want more than weight. We wanted precision.

The Old Edge and the New Spark

The blades of our ancestors were strong, yes—but crude. A flint axe could crush a boar’s skull, but it tore as much as it cut. When the beasts of the old world began to disappear and the forests thickened with smaller game, our tools had to change. I remember the first time I split a long flake from a stone and saw how fine its edge was. It was not brute force that it offered—but delicacy. With it, I skinned a hare without tearing the fur. That night, while the others feasted, I stayed near the fire, splitting flake after flake, wondering how small and sharp a tool could become before it ceased to be useful. I never found that limit.

Microliths and the Art of Assembly

The breakthrough came when I stopped seeing the stone as a single weapon and began seeing it as a part of something greater. Instead of one large blade, why not many small ones? I began embedding tiny shards into wood shafts—each one angled to slice with even the slightest pressure. I created barbed tips that locked into flesh and wouldn’t slip free. I made arrows that flew farther and straighter. These new tools—microliths, though we didn’t have a name for them then—were not only for hunting. I carved bone needles thin as a reed stalk, perfect for stitching hide. I crafted tiny hooks that caught fish without needing a net. A single spear had once been our answer to every problem. Now, we had many answers.

Teaching the Hands to Think

At first, many in the clan doubted the smaller tools. They looked fragile. Weak. “Why abandon the stone that cracked mammoth skulls?” they asked. I answered not with words, but with demonstrations. I stitched a shirt so smooth it did not chafe the skin. I made a harpoon that brought in three fish where one had been the norm. I cut firewood twice as fast with a crescent-shaped blade of tiny teeth. The doubters became curious, then eager. Soon, even the most stubborn elder was carving handles with my blades and sewing satchels with my needles. They began to see that skill, not size, was the heart of a good tool.

The Toolmaker’s Spirit

I came to believe that every tool holds a spirit—not just in its form, but in its purpose. The heavy axes of the old days were born of necessity, of survival in a harsher world. But the microliths we now used were born of thought, of care, of understanding how to work with the world rather than against it. I told the children this as I showed them how to strike stone. “The blade must not only be sharp,” I said. “It must be wise.” They laughed, but they remembered.

The Weaver, the Fisher, the Hunter

New skills bloomed alongside the tools. The weaver used my bone awl to punch holes in leather with ease. The fisher tied cords to barbed stone points and brought in trout from narrow streams. The hunter built a frame for throwing spears farther and faster, using lighter heads that didn’t shatter on impact. Even the mothers, once content with scraping hides by hand, asked for rounded blades that spared their palms. The tools reshaped us as much as we reshaped them.

I Am the Hand That Refines

Now I sit near the fire with a younger generation around me. I no longer throw spears or chase the elk, but I shape the tools that make such things possible. My hands are slower, but my eyes still see the line in the stone, the edge waiting to be freed. When I chip away at flint, I see the long arc from the days of mammoth hunters to now, where our lives are not built on force alone, but on thought, on design, on balance. I am Luma, the maker of many small things that changed everything. And though the tools I shape are tiny, the world they’ve carved is vast.

My Name is Anari the Forager-Mother: My Life in the Circle of Green

I came into the world during the moon of ripening berries, when the air was heavy with scent and the earth generous with food. My mother said I was born in the shade of a willow tree beside the stream, wrapped in bark cloth and placed on a bed of moss. Our camp was settled that season along the edge of the lake, where ducks nested and reeds whispered with wind. My clan said the land was kind that year, and I believe it, for my earliest memories are of fullness—full baskets, full bellies, full laughter.

Hands That Learn by Touch

As a girl, I learned not by words but by watching. I followed my grandmother through the fields and forests, mimicking her careful hands as they brushed past the poisonous leaves and plucked only those that nourished. I learned the colors of ripe and unripe, the sound of seeds inside pods, the smell of roots ready to pull. I knew the stinging ones and the healing ones, which bark boiled into a tea, and which leaf calmed a burn. I learned that the land speaks if you are patient. It tells you where to look. It rewards those who do not rush.

The First Bloom of Love

I was still young when I met Kael, the hunter. He moved like shadow and carried the silence of the trees in his step. I would see him at the edge of the grove, kneeling in the tall grass, always watching, always listening. He did not speak often, but when he did, it was as though the earth was speaking through him. We shared dried berries once, and later, the warmth of a fire. Our lives braided slowly, like the weaving of reeds into a basket. When he offered me a necklace of shell beads, I knew I would walk beside him from that day on.

The Strength of a Mother's Fire

My first child, Lani, was born in the early rains. I felt fear then, the deep kind that mothers know—the fear of losing, of not being enough, of the unknown. But the elder women stood beside me, their hands strong and steady. They hummed the birth songs and boiled sweetroot for the pain. When my daughter cried out, I wept too—not for fear, but for the joy of her breath. I carried her on my back as I gathered, and she learned the rhythm of my step. Later came two sons, one bold and restless like Kael, the other quiet and clever like the moon.

Feeding the Circle

My days were full, not of idleness but of purpose. At dawn, I would rise and stir the fire, then slip into the woods with a basket over one shoulder and a child on the other. I gathered what the land offered—nuts, mushrooms, greens, roots, and fruit. I dried what we did not eat, traded what we had in abundance, and taught the young ones how to share in the work. In time, I became the one they asked when unsure—Is this safe to eat? Will this leaf heal a fever? How deep must I dig for water root? I carried the memory of the land in my hands.

Loss and the Long Silence

There was a season of sickness when the rains would not stop and the rivers rose too high. Many plants rotted before harvest, and the food turned sour. My middle son, Taro, grew pale and thin. We tried every herb, every prayer, but his fire went out one cold morning. I buried him with a doll of reeds and sang the mourning chant, though my voice broke. For many moons, I could not gather. The woods seemed too still. The colors of the berries looked wrong. Only Lani, now growing tall, pulled me back with her gentle hand. She said, “Mama, the earth still waits for you.”

Seeds of the Future

In recent seasons, I have begun to notice something new. Along the trail where I once scattered seeds from a fruit, the same plants now return each spring. I told Kael, and he nodded, saying the same happens with wild grain near the marsh. We began marking these spots, tending them. We pull the weeds around the useful plants. Some call it luck. I call it learning. Perhaps, I say, the land is teaching us to stay, not forever, but longer than before. The young ones listen with wide eyes when I tell them how food can come from patience, not just the chase.

I Am of the Gathering Wind

Now, my hair is streaked with gray, and I walk more slowly, but my hands still remember. I teach the daughters of the clan to weave baskets that last, to hum to the trees as they gather, to cradle their children in slings of bark and hope. I tell them that to gather is to live, but also to give. We do not take without thanking. We do not forget the hands that fed us. I am Anari, mother of three, keeper of roots, walker of the gathering path. My story is written in leaf and soil, in lullabies and laughter, in the footprints of those who follow.

The Rise of Semi-Permanent Camps – Told by Anari the Forager-Mother

When I was a child, we moved like the wind—never still for more than a moon, never rooted longer than the animals we followed. We followed the seasons, the bloom of berries, the rustle of migrating herds. Our shelters were light, easy to pack. Our stories were carried in our baskets, our memories pressed into trails that disappeared with the rain. The land was a wide table, and we traveled across it, taking only what we needed. It was a life of movement, and it shaped my legs, my back, my hands. I knew every path, every hidden patch of wild garlic and bee nest. I knew how to walk with the earth, not stay on it.

The Camp by the Reed-Water

The change began so subtly, we did not notice at first. There was a place by the river—wide, slow-moving, with thick reeds and trees that draped like curtains over the banks. We called it Reed-Water. We stopped there one spring to rest and gather. The fish were plentiful. The roots easy to dig. The trees gave shade and strong branches for tools. And when the time came to move again, some of us hesitated. “Let’s stay a little longer,” my mother said. “Until the berries are ripe.” And so we did. Then, when the berries came, so did the ducks. Then the mushrooms. Then the deer. By the time the frost returned, we had stayed longer in one place than any season I remembered.

Learning to Return

The next year, we found ourselves back at Reed-Water without even planning to. Our feet led us there like the paths had been carved in our bones. The children remembered the trees. The elders remembered where the fire pits had been. We dug them out and kindled the old coals like greeting an old friend. We left markers this time—bundles of shells in trees, bone carvings tucked into branches—so we could find the same spots again. We began calling it our spring camp. It no longer felt like a stop. It felt like a rhythm.

Building with the Earth

It was in these returning camps that we began to build differently. No longer did we craft shelters to fall apart behind us. We tied young saplings into frames and packed the sides with clay and woven reeds. We made cooking pits lined with stone, fire-hardened bowls that stayed in one place. We shaped storage baskets with tighter lids, made from bark and sealed with pitch. I even saw Kael hang dried meat in a high tree, knowing he’d return for it months later. The camp had become more than shelter. It had become memory, embedded in soil and ash.

A New Kind of Gathering

Because we returned to the same places, we could gather in new ways. I began to notice that where I had dropped seeds or spilled berries, new plants grew stronger the next year. I began to clear space for them, gently pull back the weeds, help the plants along. I wasn’t planting like the people would in later stories, but I was listening, encouraging, guiding. We could store more food now, dry it better, share it more freely. We didn’t need to move in desperation. We moved with choice. And more often, we stayed.

The Shaping of the Circle

With semi-permanent camps came a new kind of life. We told longer stories. We taught the children songs about the landmarks around Reed-Water. We carved designs into the trees to mark births and deaths. We began to trade with other clans who also had returning camps. Our world grew richer, not because we owned the land, but because we remembered it. We became part of its story, and it became part of ours. There were still times we had to leave—floods, sickness, fire—but even then, we came back. The land forgave us, and welcomed us home.

I Am the Root That Grows Again

Now I walk more slowly, but my steps still follow the old trails. I see my grandchildren play beneath the same trees where I first learned to braid grass. I see shelters that outlast the seasons, tools that wait through the winter, and plants that return like kin. I am Anari, mother, gatherer, keeper of roots. I was born into the wandering life, but I have seen what it means to stay. Not to settle like a stone, but to return like a river. The camp is no longer just a place. It is a promise. One that we made with the earth, and one the earth has kept.

My Name is Dagan the Spirit-Teller: My Life Between Worlds

My first memory is not of waking life, but of a dream. I was a child, swaddled in elk hide, lying beside the fire, when the wind spoke my name. In the dream, an owl flew down and landed beside me. Its eyes held the night sky. It whispered, “You will see what others do not.” When I awoke, my mother said I had cried out in words too old for her to understand. From that day on, I was no longer just a child of the clan. I was one of the dream-called, a spirit-teller in the making.

The Eyes of the Ancestors

I grew up between the fires of the living and the shadows of the unseen. While other children learned to throw spears or gather roots, I learned to read smoke. I listened to the wind in the reeds, traced the stars with my fingers, and watched the animals for signs from beyond. The elders taught me the chants passed from tongue to tongue like sacred fire. They painted my face with ash and ochre, and I learned to sit in stillness so long that even the deer forgot I was there. The land itself became my teacher, and the dead my whispering companions.

My First Crossing

I was thirteen winters when I crossed into the spirit world for the first time. Fever had taken hold of me, and my breath came shallow. The clan gathered, thinking I might not return. But as my body weakened, my mind soared. I traveled through fire, through water, through darkness. I met a figure made of smoke who gave me a flute carved from bone. “Sing the song of memory,” it said. When I awoke, I found my voice had changed. Deeper. Stronger. And in my hand was a stick of charred wood shaped like the flute. I carved it myself that night, though I do not remember how.

Keeper of the Painted Cave

When I came of age, the elders brought me to the cave of the ancestors. Its walls were alive with the stories of our people—painted stags, spirals, hands, beasts of old. They placed a burning torch in my hand and told me to walk alone. As I passed through the chambers, I felt the presence of every spirit who had ever walked with us. I added my mark—three lines to represent the path: the world of breath, the world of shadow, and the world beyond. From that day, I became the keeper of the stories. The one who speaks when others sleep.

The Ritual of Fire and Smoke

Seasons passed, and I guided the clan through sorrow and joy. When children were born, I painted their foreheads with red clay. When the sick hovered between worlds, I sang their spirit songs. When the dead were returned to the earth, I danced through the smoke, calling their names to the wind. I taught the others to respect the unseen—to leave offerings to the river, to whisper thanks to the hunted, to look for signs in the flight of birds. I did not command, but reminded. The sacred is not distant. It is underfoot.

Visions of Change

In the time of Kael and Anari, I saw great changes stir. The land grew restless. The rains shifted. New animals came. Some among us began to speak of staying in one place, of tending the land as one tends the fire. In my dreams, I saw stone circles rising and children born under unfamiliar stars. I felt the breath of ancestors who had not yet been born. It is the way of time, I told the young ones. What we are is not fixed. The spirit dances like flame—changing shape, but never disappearing.

The Night I Sang the Stars

There was a night when the sky cracked open with light. The stars fell like ash from a great fire, and the children cried out in fear. I stood atop the hill and sang the old song—low, steady, with the rhythm of the earth. They gathered around me, hearts trembling. “The sky speaks, not to harm, but to remind,” I told them. “We are small, yes, but we are not forgotten.” That night, even Kael sat in silence as I drew the sky’s story into the dirt. And Anari placed a circle of flower petals around the fire.

I Am the Song Between Worlds

Now I walk more slowly. My bones creak with the age of many seasons. My hair is white, and my hands stained with years of ochre and ash. But the spirits still walk with me. When the wind rises suddenly, I know it is them. When a fox crosses my path at dusk, I nod in respect. The children come to me with their dreams, and I help them listen. My voice is quieter now, but the stories are louder than ever. I am Dagan, Spirit-Teller, friend to both the living and the dead. My life is not a straight path, but a circle, always returning, always whispering.

Hunting with Strategy and Cooperation – Told by Kael the Hunter-Tracker

I was born into a world where the old ways of hunting still echoed in our stories—where men hurled heavy spears at giant beasts and returned with bruises and glory. My grandfather had done that, standing shoulder to shoulder with five others, their muscles straining against the will of a mammoth. But by the time I could walk, the herds had changed. The giant ones were gone, the land warmer, the forests thicker. What we hunted now were swift, clever, and easily lost among the trees. A hunter who ran alone returned empty-handed. It was no longer about strength. It was about thought. About patience. About working as one.

The Wisdom of the CircleThe first lesson I ever learned was to watch—not just the prey, but the people around me. My father would crouch beside a trail and trace lines in the dirt with a stick, showing me where the deer passed and where we would hide. He’d say, “Don’t chase the deer. Chase the place it’s going.” With three or four of us working together, we shaped the hunt like a river—one scout to track, two to drive the animal, and one to wait in silence. We used our voices like bird calls, our feet like shadows. When we moved as one, the prey never saw the end coming.

Traps and the Patience of StoneOne winter, the game grew thin. We had to think beyond the chase. That was when I began to study the bend of branches, the way a fallen rock could be balanced just so, the path a rabbit always took through the same patch of bramble. With help from Luma, we began building traps—not large ones, but clever ones. A loop of sinew hidden in grass. A deadfall triggered by a twig. Traps did not rely on speed or luck. They waited. They worked while we slept. Soon we had lines of them running through our camp’s edge, checked each morning like the turning of a page. It was a quieter way to hunt, but no less rewarding.

Fishing the Silent WatersWhen the forest was still and the game elusive, the rivers fed us. At first, we fished with spears—sharp and fast, thrown from the shallows. But the fish were quick and darted like flickers of light. So we adapted. We carved barbed hooks from bone, tied with twisted sinew, and baited them with insect grubs. We wove nets from reeds, heavy with stones at the bottom, that we dropped into the deeper pools. Luma even crafted a scoop with fine webbing to catch minnows for drying. Fishing was not just food. It became a craft, a calm art of stillness, and the river taught us in return.

The Coming of the DogIt was in my twentieth winter when the first dog became more than a shadow at our fire. A wolf pup had wandered into camp, lean and hungry, and I tossed it a bone out of habit. He didn’t run. He stayed, watched, and curled beside my feet that night. We named him Raka. As he grew, he followed me into the forest. At first, he chased too soon, barked too loud—but he learned. He learned where to wait, how to signal, when to stay. And I learned to listen to him. He scented prey before I did. He found wounded game in the brush. He warned of other animals before we saw them. More pups came after him, more bonds were formed. With dogs at our side, the hunt became not only easier—it became kinship.

The Power of the AtlatlI still remember the day I first used the new thrower. Luma handed it to me, a carved wooden lever with a small hook at the end. “It will make your arm longer,” he said. I laughed, but tried it. I placed my spear into the groove, wound back, and let it fly. The spear sang. It struck farther and faster than I ever could have managed alone. With the atlatl, I no longer needed to creep as close or risk the final charge. We practiced every evening, adjusting weight and length. Our hunts became cleaner. Less danger. More certainty. The thrower became part of us, like a third arm shaped by knowledge.

I Am the Hunter Who ListensI no longer run as far, nor crouch as long in the snow, but I teach the young ones what it means to hunt with care. To move with others, not in pride. To set traps not out of laziness, but out of wisdom. To see the dog not as tool, but as brother. To wield the atlatl not with force, but with grace. The hunt is no longer a thing of brute will. It is a song, sung in parts—by man, by dog, by wind, by river. I am Kael, hunter of the new age, tracker of the unseen path. I do not chase the beast. I walk beside it, and I understand its ways.

Foraging and the Knowledge of Plants – Told by Anari the Forager-Mother

Before I could speak full words, I could spot wild garlic. Before I could carry a basket, I knew which mushrooms to never touch. The forest was my first teacher, and my mother was its voice. She would hum softly as we walked, her hands brushing gently over leaves, her eyes always searching. “The land speaks,” she told me, “but only if you listen with more than your ears.” I learned to feel the roughness of nettle before I saw its sting, to smell the sharpness of mint from ten paces, and to watch the bees, who always knew where the sweetest flowers grew. To forage was not to take—it was to know.

Gathering What the Earth GivesThe seasons were like a great woven cloth, each thread bringing new gifts. In early spring, we gathered young greens—wild spinach, sorrel, and nettle, which stung if you were careless but fed us when boiled into stew. As the sun warmed the soil, the berries came. Blue ones that burst on the tongue, red ones we dried and packed, and dark ones that stained our fingers and faces. In the heat of summer, we dug for wild carrots and parsnips, their roots twisted and stubborn but sweet. We cracked open nuts in the fall—hazelnuts, walnuts, acorns soaked to wash away their bitterness. And always, the mushrooms—some to savor, others to fear. I learned their secrets from my grandmother’s stories, told as we walked the same paths over and over again.

The Tools of the GathererWe carried baskets woven from reed and bark, shaped not just for holding, but for sorting—one for roots, one for seeds, one for greens too soft to crush. My own hands became tools—my fingers nimble, my touch gentle. I used digging sticks carved by Luma, strong enough to pry free the stubborn yams. I used flat stones to grind seeds into powder, and shells to scoop out sticky honey without angering the bees. Foraging was not a rush—it was a rhythm, a conversation with the land. You never took all. You never damaged the roots. You always gave thanks, even if only with a whispered word.

Seeds That ReturnedThere was a patch near Reed-Water where we often sat to rest. I once dropped a handful of berry pulp there by accident, busy with a crying child. The next season, the same berries grew, stronger and nearer than before. I remembered. I watched. I tried again. I began to scatter seeds in places we returned to—near the stream, at the edge of the shelter, in soil that stayed moist but not flooded. And again, they came back. It was not like planting, not as the future people would know it. But it was something new—something between wild and tended. We began to clear patches of thorn to let good roots breathe. We left seeds near camps we’d return to. Slowly, the line between gathering and growing began to blur.

Passing the Knowledge Root to RootI never kept this knowledge for myself. As the clan walked, I taught the children the songs of the plants—the chants that named each root, each leaf, each warning. We used rhyme to remember what healed burns, what helped sleep, what eased the pain of birth. I marked certain trees with cuts so others would know when the sap ran sweet. I told stories of the first woman who learned to dig, the spirit of the hazelnut who shared its shell. Plants were not objects to us. They were neighbors, elders, even tricksters. And we respected them as such.

The Birth of BalanceIn time, we learned to live not just from the land, but with it. We began to tend patches of grain where the stalks bent heavy and golden. We shaded fragile herbs with larger leaves. We shaped the land as gently as a mother shapes her child. Foraging became more than survival. It became stewardship. We became part of the cycle, not above it. And in doing so, we found something deeper than food. We found peace.

I Am the One Who Listens to LeavesNow I walk slower, but the forest still speaks to me. When the breeze rustles the tall grass, I still hear the voice of my mother. When I taste the first berry of the season, I still feel my daughter's tiny hand in mine. I am Anari, the gatherer, the teacher, the mother of the path between wild and cultivated. My baskets are worn, my fingers bent with time, but my heart still blooms with every green shoot. I did not invent the garden. But I felt its first breath. And I taught my children to breathe it in, too.

Spirituality, Totems, and Cave Paintings - Dagan the Spirit-Teller

I was not chosen by people, but by dreams. When I was still a boy, before my voice had deepened, I would sit too close to the fire, staring into the shifting light. My clan thought me strange. While the others played or practiced with stone tools, I listened to things they could not hear—the breath of the wind through the grass, the sigh of the earth as the sun slipped behind the trees. One night, I woke from sleep gasping, clutching a vision of a stag with hands painted across its back. I told the elders. They painted my brow with ash and said, “You are one who walks with shadows.” From that night on, I became the watcher of what cannot be seen.

The Spirit in All ThingsTo us, the world is not dead matter. The stones remember. The trees feel. The rivers carry stories. Every creature we meet walks with a spirit, just as we do. When Kael hunted, he gave thanks before the kill and whispered to the fallen beast after. When Anari gathered roots, she left strands of her hair behind as a gift to the soil. We do not own the land or rule over it—we walk among its many voices. I was taught to speak with these spirits through dream, through trance, through song. I fasted in the hills. I bathed in cold streams. I let myself become hollow so the world could fill me.

The Totems That Guide UsEach clan has its guide, its protector spirit. Ours was the raven—clever, sharp-eyed, a messenger between sky and earth. I wear its feathers woven into my cloak. Others wear the wolf, the deer, the serpent, the bear. These are not decorations. They are echoes of who we are. When a child is born, we watch closely for signs: the dreams they murmur, the way they crawl, the animals drawn to them. When their totem reveals itself, we carve it into bone or stone, string it around their neck. I have carved many in my time—delicate talismans from antler or ivory, given not to control the spirit, but to honor it.

The Painted CavesThere are places deep beneath the ground where the breath of the earth hums in stone. In these caves, we speak with the old spirits. I was led to one as part of my passage from boy to teller. Inside, flickering torchlight revealed walls covered in ochre-red beasts—bison, stags, horses, and human hands like fading echoes. I asked who had painted them, and the elder simply said, “We all do, in time.” The cave became my temple. I returned often, bringing the crushed pigments of berries, charcoal from the sacred fires, and brushes made from moss or feather. Each image I added was a prayer, a story, a message to those who would come after. Not all could read them, but the spirits always could.

The Rites of Death and ReturnDeath is not an ending. It is a crossing. When one of our own passes, we do not burn them or leave them behind. We bury them with gifts—food for the journey, beads for the ancestors, tools to remind them of the life they lived. Sometimes, we paint their faces with red ochre, the color of blood and fire, of life continuing. I sing over them, calling to the spirits of the hills and the wind, asking them to guide the soul to its next resting place. And in dreams, I often see them again—walking beside the river, smiling, unburdened by hunger or pain.

Symbols That Speak Without WordsBefore our mouths learned the stories, our hands told them. Lines carved into bone, spirals etched into stone, circles that mark the turning of seasons—these are the language of the soul. I have seen children trace these symbols without knowing what they mean, only to dream of the same shape that night. The world speaks in patterns. The sun, the moon, the tides, the heartbeat. We try to match those rhythms with the images we leave behind. Some are meant for the spirits. Some are meant for us. And some are for those who are yet to be born.

I Am the Fire That RemembersNow I walk slower, and the firelight is kinder to my old eyes. But the dreams still come. The spirits still visit. I still hear the calls of unseen wings in the night. My hands still mix ochre, still carve bone, still light the ritual flames. I am Dagan, spirit-teller, cave painter, singer of the soul’s path. I do not seek answers in the stars—I speak with them. I do not fear death—I have walked its path too many times. What we are is not what we hold or hunt or build. What we are is what we honor, what we remember, and what we leave behind in paint, stone, song, and silence.

The Power of Community and Family Roles – Told by Anari and Kael

Anari: When people speak of us, they often imagine each of us alone—hunter, gatherer, child, elder—each in their separate place. But that was never true. Our lives were woven together, like the baskets we used to carry food or the mats we slept on. Every morning, as the smoke rose from the hearth and the first light kissed the trees, we met by the fire. That was where the day began—not in strength, not in silence, but in sharing. We spoke. We planned. We listened. The campfire was our center, not just of warmth, but of understanding.

Kael: When I returned from the hunt, it was not victory I sought—it was the voice of my people. Anari’s stories about which plants bloomed early, Dagan’s warnings from his dreams, the children’s laughter as they mimicked the deer’s leap. These things told me more about our world than tracks in the mud. And when I left again, I did not go alone. I went carrying the work of many—snares crafted by the young, tools repaired by Luma, blessings whispered by the elders. Every hunt was a village effort, every meal the result of many hands.

Roles Without WallsKael: There were days when I set down the spear and helped bind together shelter poles, when the storm winds threatened to tear our camp apart. And there were days when Anari, usually with her basket full of greens, took up a bow and tracked birds through the trees with the patience of any seasoned hunter. We did what was needed. There were no walls between men’s work and women’s work. There was only the work, and the will to do it.

Anari: I taught my sons to gather. I showed them which roots to avoid and how to carry without crushing the berries. I taught my daughter to tan hides, to sharpen tools, and once, to set a snare. She caught a rabbit that day, and her smile lit up her face like the sun after rain. We gave our children what they needed, not what some invisible rule said they should have. If someone had the hands for weaving or the eyes for tracking, that gift was honored—whatever their age or role. The land does not judge. Why should we?

The Strength of the EldersAnari: The elders were never left behind. They held more knowledge in their silence than we could gather in a dozen seasons. My grandmother had long lost the strength to walk far, but her memory stretched back farther than any trail I ever followed. She remembered the last great frost. She remembered the cave before we painted it. When we sat by the fire, her voice was the thread that connected all the rest of us.

Kael: There were times on the hunt when I remembered a path my father had spoken of, or a wind he had warned me would shift. He died many winters ago, but I still hear him in the way the birds scatter. When I taught my own son to track, I passed along not just what I had learned, but what had been given to me. The elders gave us roots, so that we could stand tall when the wind came. Without them, we would have been leaves in the storm.

The Children Who Watch and BuildKael: The young ones were never idle. From the moment they could walk, they followed us, watching, imitating, asking endless questions. I once found my son crouched in the mud, practicing how to move without breaking a twig. He had no spear yet, but he already understood the silence of the forest. That was how we learned—not from commands, but from presence.

Anari: My daughters stirred the stew before they could name every root in it. My sons listened to the stories of Dagan with wide eyes, imagining spirits in every shadow. The children learned because they lived among the doing. And when the time came, they did not need to be told they were ready. They already were. They had been part of it all along.

We Are Threads in the Same WeaveAnari: There is no strength in standing apart. Our lives are braided together, like the cords we twist from grass—each strand weak alone, but together strong enough to carry a deer across miles. Every voice matters. Every hand carries something. When we move, we do so like a flock of birds, shifting and soaring, following the wind together.

Kael: I have tracked alone. I have walked in silence so long my own breath seemed too loud. But I always returned. Because the hunt is only half the story. The other half is in the firelight, in the shared meal, in the quiet conversation between a mother and child, between an elder and a listening ear. That is what makes a people. Not weapons. Not walls. But weaving lives into one another.

Anari: I am the mother who gathers, the voice that comforts, the hands that teach.

Kael: I am the hunter who listens, the guide who remembers, the feet that return.

Together: We are the clan. We are the fire. We are one.

The First Steps Toward Domestication – Told by Luma the Toolmaker-Innovator

It began not with a plan, but with a pause. A young wolf—thin, unsure, with ribs like river stones—watched us from the edge of the trees. Most wolves kept their distance, their yellow eyes sharp with hunger and warning. But this one didn’t run. He sat. He watched. I tossed him a scrap of fish skin, more out of curiosity than kindness. He took it and stayed. The next night, he came closer. By the fourth, he lay by the fire’s edge, ears flicking but body calm. We named him Jaro. He was not like the others anymore. He had crossed some invisible line between them and us. And once he crossed, others followed.

The Bond Forged in SilenceJaro didn’t need training. He learned by watching, by living among us. When Kael hunted, Jaro tracked beside him, silent and swift. When we gathered, he circled the camp, ears up, warning us when danger neared. He barked once at a boar before it reached our children. From then on, he was no longer “the wolf that came.” He was ours. In time, pups born near the fire became calmer, friendlier, more eager to stay. We fed them, yes—but more than that, we trusted them. They became our companions. Not tools. Not slaves. Friends. And with that friendship, the wild shifted.

The Grain That ReturnedThe change was slower with the plants. There was a patch of wild grain not far from Reed-Water. Anari always gathered from it, careful to shake the seeds loose before cutting the stalks. One year, we returned and found the patch had doubled. The next, it had tripled. It was as if the land remembered us. Or maybe we had helped it remember itself. We cleared the thornbrush nearby and scattered seeds there. We didn’t call it planting. We called it helping. But the truth was, we were shaping the wild in our image, even if we didn’t yet know it.

Tools to Shape the LandWhen I saw the grains growing thicker, I made a digging stick stronger than the last. I carved ridges in the handle to fit the hand better. I bent the tip with fire to scoop more easily. I shaped flat stones to grind the seed into a coarse flour, which we cooked over fire into thick cakes. Before, we ate what the land offered. Now, we helped decide what it would offer. Not command—but coax. Not force—but guide. The tools we used were not just for taking anymore. They were for tending.

Walls Without StoneAs some plants grew better near camp, we noticed something else. Deer no longer passed through freely. Birds came to peck at the grains. So we built small fences—not strong, not high, but enough to say, “this patch is watched.” They weren’t meant to keep the world out, only to give the plants a chance. We placed stones in circles around young sprouts, tied feathers above to scare the birds, laid paths between rows so we wouldn’t trample what we hoped would return. These were the first lines drawn between wild and tended.

Becoming Part of the PatternEven as we shaped the land, we knew we were still part of it. The wolves did not become pets—they remained hunters, only now, hunters beside us. The grains were not owned—they were nurtured, and sometimes lost to flood or wind. But the line between what was natural and what was human had begun to blur. We were no longer just guests of the earth. We had begun, gently, to become caretakers.

I Am the One Who Listens ForwardNow, when I sit near the fire with children watching me carve tools, I tell them these changes were not sudden. The dog was not born by command, nor the grain by design. They came slowly, through trust, through care, through listening. I am Luma, shaper of wood and stone, follower of patterns, reader of change. I have seen the wild lean closer, not out of fear, but out of hope. And in return, we have leaned toward it, not to tame it—but to meet it halfway. These were our first steps toward something new. Not the end of the old ways, but the beginning of a deeper bond with the world that made us.

Ritual and Music of the Ancients – Told by Dagan the Spirit-Teller

I do not remember my first step, but I remember my first song. It was not sung with words but with drum and breath and the beat of feet on packed earth. My mother held me in her arms beside the fire as the others circled and moved, each step a rhythm, each clap an offering. The fire cracked in time with their chant, and the night air pulsed like a great heart. That was when I first understood that music was more than sound—it was spirit made real. It was not something we made. It was something that moved through us.

The Drumbeat of the SeasonsThe year was a great turning wheel, and each point on its edge was marked by sound. When the first shoots of green pushed through the soil, we drummed low and soft, mimicking the heartbeat of the waking earth. When the heat of summer reached its peak, we played fast and sharp, like cicadas calling for rain. When the first leaves fell, we sang songs of letting go. And in the deepest winter, we sang only in whispers, so the cold spirits would not hear our warmth and grow jealous. The music taught us how to feel what the land felt. It reminded us we were part of its breath.

The Paint of the SoulBefore we danced, before we sang, we painted. The ochre came first, always. Red for life. Then charcoal, black as the night cave. Then white from crushed shell or bone. Each line drawn on the skin had meaning—a spiral for the sun, a dot for rebirth, lines for the rivers of the spirit world. On the day of a child’s naming, we painted the forehead and palms. On the day of mourning, the feet and chest. On days of harvest and renewal, we painted the whole body, becoming walking offerings to the unseen. When the spirits looked down, they saw not only humans, but sacred shapes in motion.

The Circle of Sound and FlameOur ceremonies were never still. The circle was our sacred shape—no beginning, no end. We danced in spirals around the fire, our feet finding the beat, our voices rising in rhythm. Some chants had no words, only vowels stretched like the wind through trees. Others were stories—of ancestors who walked into the stars, of wolves who guarded our dreams, of lovers turned into rivers. Children learned these songs before they could speak in full sentences. The old ones remembered verses the rest of us had forgotten. Every voice mattered, every body part of the whole.

Birth, Death, and the Music BetweenWhen a child was born, we sang not to celebrate, but to welcome. The song was soft, high, like wind through reeds. It was the same tune each time, passed from mouth to mouth like a blessing. We whispered it in the child’s ear so they would remember it in dreams. When someone died, we did not wail. We drummed. Slow, steady, the beat of a departing soul. We painted their face, placed feathers on their chest, and chanted their name three times so the ancestors would hear. And after, we danced—not for joy, but to honor their journey, to remind the world they had moved through us.

Instruments Born from Bone and BreathNot all music was made with the voice. We made flutes from bird bones, short and high-pitched like the morning songs of the hills. We tied pebbles in gourds to shake like the storm. We strung sinew across bent wood, plucked it to mimic the groan of trees. Luma helped shape a hollow drum from fire-hardened bark and stretched hide. It was not loud, but deep. When I beat it during rituals, I felt the sound in my ribs, as if the earth itself had a voice. These instruments were not played—they were invited to speak.

I Am the Echo of the Old SongsNow, my voice is rough, my hands slower with paint and drum, but I still hear the music. In the wind between the trees. In the crackle of the fire. In the silence that follows the last note. I am Dagan, spirit-teller, song-bearer, painter of the flesh. I remember the songs that came before language, the dances that stirred the ground, the chants that held the world together. Our rituals were not superstition. They were survival. They reminded us that we were not alone. That we were surrounded—by the living, the dead, and the spirits who dance in the spaces between. And through rhythm, through paint, through song, we joined them. Always.

Surviving Together: Climate, Change, and Resilience – Told by AllDagan: The world has always changed. The stars may follow their paths, but the earth twists and breathes in ways both slow and sudden. My grandfather spoke of a time when the north was wrapped in endless ice, when beasts with hair like grass walked across frozen rivers, and the air bit the skin even under furs. That time passed. The ice melted. The rivers grew, then broke their banks. Forests marched into the grasslands. What we now call change is not new. It is only the latest song in a long, long chorus.

Kael: I’ve walked lands that were once hunting trails, now swallowed by water. One spring, the river near Reed-Water rose so fast it tore through our camp. We had no warning—only the distant roar and the shaking of the ground. We ran, barefoot, soaked, holding children and baskets above our heads. By the next moon, the fish had found new streams, and so did we. I learned that the land does not promise to stay the same. Our strength was never in holding it still—but in knowing when to move.

The Dry Years and the Silent HarvestAnari: There were years when the rain forgot us. The berries dried before they ripened. The roots cracked in the soil. Even the bees vanished for a season. We walked farther each day to gather enough for one meal. The children grew thinner, the elders quieter. But we did not give up. We soaked seeds in clay to hold moisture longer. We rose earlier, before the sun baked the land. And we shared. Always. No one hoarded, because all knew hunger. It was not the dry wind that defeated people—it was the turning inward. We stayed open, and so we survived.

Luma: It was during those dry years I began shaping tools differently. Digging deeper. Sharpening faster. I watched animals dig small holes and find water below. I mimicked them. We carved troughs to catch dew. I bound hollow reeds to carry water farther from springs. The heat taught me that even stone and bone must adapt. Every hardship the earth gave us became an invitation to learn.

Waves of People, Trails of MemoryKael: We were not the only ones to feel the change. Other clans came—some hungry, some afraid, some fierce. At first, we feared them too. They took our game, crowded our trails. But we sat with them by the fire, traded stories, shared fish, argued over space, and found a rhythm. We had to. The land could no longer carry each of us alone. What we called migration was not escape. It was return—return to movement, to shared struggle, to the truth that we do not walk this earth alone.

Dagan: I’ve dreamed of places far beyond our paths—of lands swallowed by sand, of trees growing where none had before. I believe the spirits guide all who listen, even when they carry different names. The earth calls all people to move when the time is right. The challenge is not the journey. It is how we treat one another on the road.

Seeds of Tomorrow in the Soil of TodayAnari: When we found a dry patch that once bore fruit, we left seeds there anyway. Not for us, but for those who might come later. I began to carry seeds not just for eating, but for leaving. In clearings, near water, along paths we traveled. These were offerings to the future. And some came back. Sometimes, we returned to find our old camps flowering again. Sometimes others did, and left us messages carved into bark—symbols of thanks, spirals of hope.

Luma: That’s when I realized we were no longer just taking from the land. We were shaping it. Gently, yes. Without walls or chains. But shaping it all the same. Domestication didn’t begin with fences—it began with memory, and with choice. To return. To plant. To care. That is where the first spark of civilization was born—not in fire, but in stewardship.

The Sky Still ChangesDagan: I tell the children that the world breathes in great cycles—warmth and cold, flood and drought, stillness and movement. The earth has shifted its skin many times. Even before we walked upright, the glaciers came and went, the seas rose and fell. What we feel now is only the echo of ancient rhythms. This is not a punishment. It is a reminder. That we are small, but not helpless.

Kael: We adapt, because we must. But we endure, because we stand together. Not just hunter beside hunter, but elder beside child, gatherer beside toolmaker, neighbor beside stranger. The world has never waited for us to be ready. But together, we have always found a way forward.

We Are the Story That Bends, Not BreaksDagan: I am the voice that remembers the old winds and listens for the new.

Kael: I am the feet that move when the trail vanishes.

Anari: I am the hands that plant what may not bloom for many seasons.

Luma: I am the maker who shapes tools for a world still becoming.

Together: We are the people of the shifting earth. We do not fear change. We walk with it. And in doing so, we carry the future on our backs, like fire wrapped in moss, ready to light the next camp, wherever it may be.

The Turning of the World: A Discussion of the Neolithic Revolution – Told by AllAnari: I remember the first time someone called our camp a “village.” It startled me. We had always moved—following the seasons, the herds, the blooming of certain berries. But now, we had stayed long enough that the trails around our shelters were worn like river paths. The fire pit had been rebuilt three times. Children were born and had never known another place. The people planted, tended, harvested, and then… stayed. What once felt like a pause became a choice. This was no longer a resting place. It was becoming home.

Kael: I resisted it at first. My bones were shaped by movement. My eyes trained to scan horizons, not fences. But I saw the good it brought. The children grew stronger with steady food. The elders could sit in comfort instead of being carried from camp to camp. We had time—time to make things last, to carve stories into stone, to remember. I did not forget the forest, nor the way of the hunt. But I learned there is a kind of strength in standing still when it serves the whole.

The Fields That Fed the FutureAnari: Before, we gathered what grew wild. But now, we returned to certain patches not by chance, but by plan. We cleared weeds. We watered. We watched. Wild barley, lentils, chickpeas, bitter roots made sweet through boiling. We buried seeds with care and prayed over them. And they came back—again and again. It was a new kind of rhythm, one born not from chase but from patience. We no longer lived from what the land gave. We shaped the land to give more.

Luma: And as the crops changed, so did our tools. I built heavier grinders for grain, stronger digging sticks, stone sickles with sharp edges and curved bones for handles. Clay pots for storage. Baskets lined with pitch. New problems led to new inventions. Spoiled grain, rodents, rain—all of these taught us how to build better. We dug storage pits. We built raised platforms. We started working not for the day, but for the season ahead. That’s when I realized we had stepped into a different world.

The Rise of Roles and RanksDagan: When people live close together, they begin to look inward. Not just at the soil, but at each other. Some were better at growing. Others at shaping, at organizing, at leading. I began to notice that not all voices were equal anymore. Decisions once made by many were now made by a few. Not by force, not at first—but by habit, by convenience. The one with the granary key became the one others followed. The one who spoke with neighboring villages became our voice. Hierarchy crept in like moss on stone—slow, quiet, but spreading.

Kael: We began to see homes that stood larger than others. Families who traded more, owned more, decided more. It unsettled me. We had once shared everything. Now, some began to keep. Still, not all change is wrong. The hunters who brought in more meat still fed the clan. The gatherers still shared. But something had shifted. Power had taken root, just like the seeds in the field.

The Web of Trade and MemoryLuma: With permanence came things worth trading. Not just food, but tools, cloth, beads, stories. I made blades that ended up two valleys away. In return, we received obsidian, dried fruit, painted pottery. It was thrilling—and dangerous. Strangers now came with hands open or fists closed. Some brought peace, others brought warning. We began to mark boundaries. To speak of “ours” and “theirs.” The world grew wider and more tangled. And we found ourselves tied into it by the things we made and needed.

Anari: I traded dried herbs for woven mats. Gave grain for salt. Once, I received a necklace made of seashells—seashells! The sea was many weeks’ walk away. I held them in my hand and felt the pull of a world I would never see. Trade brought wonder. But it also brought risk. Sickness. Conflict. Jealousy. We had to learn new kinds of wisdom—to choose who to trust, and when to protect what we had grown.

The Spirit in the Stone WallsDagan: When people live long in one place, they begin to leave more than footprints. They begin to shape the unseen. We painted not just caves now, but homes, pots, walls. We carved symbols, built shrines to the rain, to the sun, to the gods of grain. We buried the dead beneath the homes of the living, honoring the cycle. Birth rituals grew longer. Death songs echoed across the hills. As life became more complex, so too did our need for meaning. The spirits did not leave us. They followed us into the villages—and took on new names.

Kael: I still sang to the wind before a hunt, still whispered thanks to a fallen stag. But now we had gatherings that lasted through the night—chants, drums, painted hands held high. We sang for the land not just to feed us, but to stay with us. To not change again. We were no longer just surviving. We were asking to belong.

We Are the Children of the Turning TimeDagan: I remember the old ways. I walk in the new. I see the threads between them—tightening, stretching, binding us to each other and to the earth.

Kael: I once hunted across the open plain. Now I hunt memory, teaching young ones not just to kill, but to know where they came from.

Anari: I planted food for my children. I now plant wisdom—for those who will live in homes I will never see.

Luma: I once made tools for hands. I now make tools for villages, for futures, for ideas.

Together: We are the voices of the Neolithic. The ones who stepped from forest into field. From wandering to dwelling. From sharing a fire to shaping a world. We did not know we were beginning something vast. We only knew we were changing. And that we would do so—together.

Comments