4. Heroes and Villains of the American Melting Pot: Politics: Northwest Ordinance and Early Restrictions of Slavery

- Historical Conquest Team

- Dec 3, 2025

- 39 min read

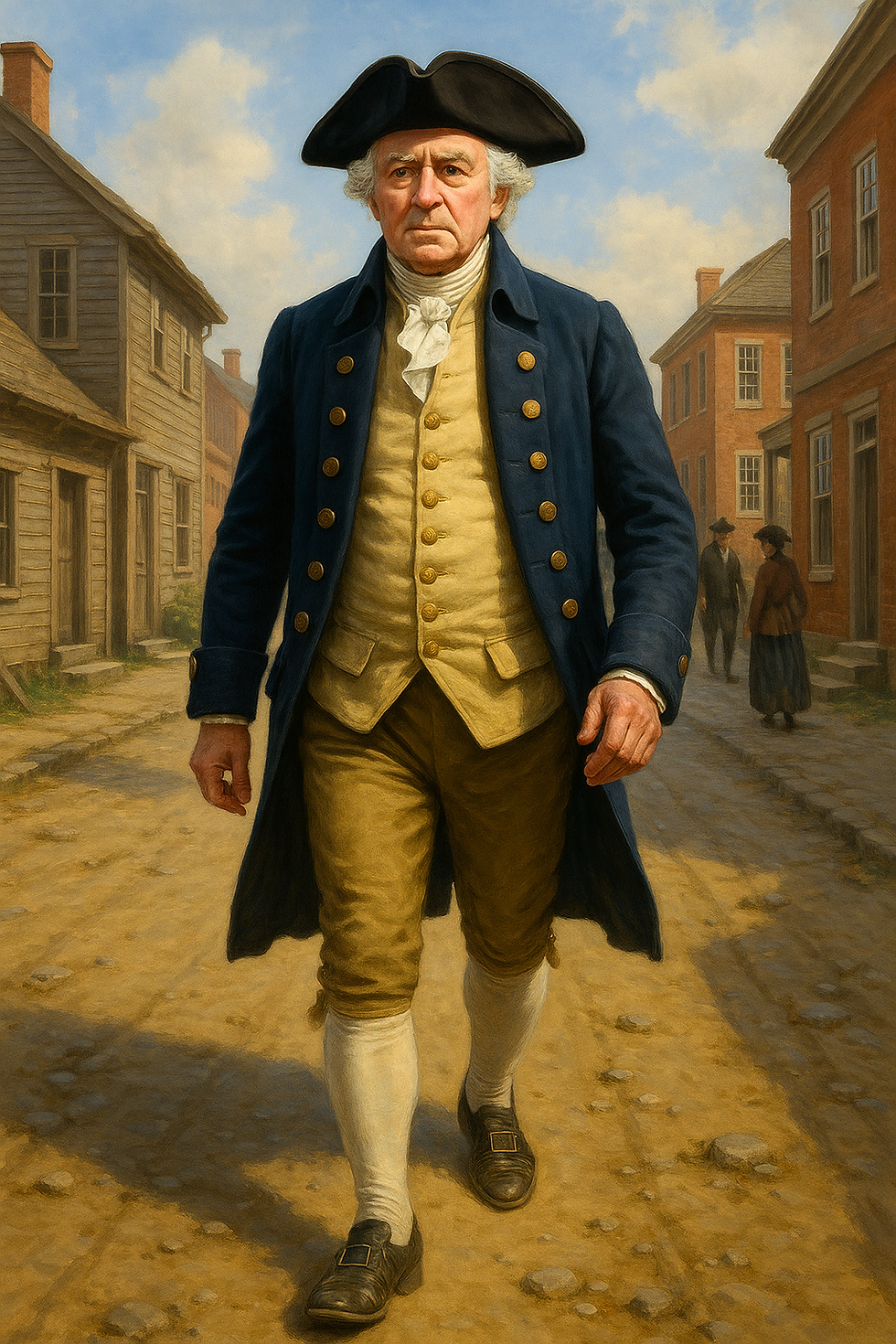

My Name is Nathan Dane: Author of the Northwest Ordinance

I was born in 1752 in Ipswich, Massachusetts, a quiet coastal town shaped by hard work, faith, and a deep belief in education. My family was not wealthy, but we valued learning, and from an early age I developed a habit of study that guided the rest of my days. The colonies were still under Britain’s authority then, but change was in the air, and a young mind like mine could feel the tension rising.

Becoming a Lawyer and Entering Public Service

I pursued law with determination, studying under some of Massachusetts’ most respected legal thinkers. By the time the Revolution began, I was practicing law and helping shape local responses to the crisis. I never became a soldier, but I served my country through legislation and legal work, believing that a stable framework of laws was just as essential to winning independence as muskets and powder.

Serving in the Confederation Congress

After the war, I was chosen to represent Massachusetts in the Confederation Congress. It was a turbulent time. The Articles of Confederation were weak, the states often quarreled, and the new nation struggled to find its footing. Yet it was precisely in this fragile environment that I saw an opportunity to shape something lasting—a system for governing the vast western lands that would determine the character of future states.

Writing the Northwest Ordinance’s Defining Clause

In 1787, during one of Congress’s most crucial sessions, I drafted a clause that would forever change the nation: the prohibition of slavery in the Northwest Territory. When I proposed it, I expected fierce resistance. Instead, to my surprise, the measure passed with little opposition. I wanted to ensure that the new territories—Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin—would grow as free societies and provide a model for future expansion. That single clause became one of the most influential antislavery measures in early American history.

The Ordinance’s Broader Vision

The Northwest Ordinance did more than ban slavery. It established civil liberties, religious freedom, public education, and a three-stage path to statehood. I believed deeply that new states must join the Union not as colonies but as equals. I wanted settlers to enjoy the rights and protections of the original states, ensuring a unified republic rather than a fractured empire. Though I was just one man in a room of many, I helped craft a blueprint the nation would use for generations.

Later Career and Contributions to Law

After leaving Congress, I returned to Massachusetts and devoted much of my life to legal scholarship. I helped revise the state’s laws, served in the legislature, and eventually played a part in founding the Massachusetts constitutional convention. One of my greatest intellectual achievements was my multi-volume legal digest, a comprehensive study intended to strengthen the legal profession and clarify American jurisprudence for future generations.

Reflections on Legacy and Principle

As I grew older, I watched the nation wrestle with the very crisis I had hoped the Northwest Ordinance would soften—the struggle over slavery’s expansion. My work did not end the conflict, but it drew a line in the early years of the republic, proving that Congress had both the power and the moral responsibility to limit slavery where it could. When I died in 1835, I took comfort in knowing that I had helped lay a foundation for a freer nation, even if future generations would have to continue the work.

The Articles of Confederation: Early Weak Federal Power – Told by Nathan Dane

When I first entered the Confederation Congress, I found myself not in a grand governing body but in a fragile assembly struggling to hold thirteen independent states together. The Articles of Confederation had been written during the Revolution, when fear of tyranny overshadowed the need for national unity. As a result, Congress possessed almost no real authority. It could recommend, request, and appeal to the states, but it could not compel them. Every action depended on the goodwill of thirteen separate governments, each more concerned with its own interests than with the collective future of our young nation.

No Power to Tax, No Power to Enforce

One of the gravest weaknesses of the Articles was Congress’s lack of power to raise revenue. We had fought a costly war and accumulated enormous debts, yet we could not levy taxes. Instead, we sent polite requests to the states, hoping they might send what we needed. Often they did not. Without funds, we could not pay soldiers, maintain diplomatic commitments, or support essential institutions. Even if Congress passed a resolution, we had no executive branch to enforce it and no judiciary to interpret it. The national government existed more in theory than in practice.

The Western Lands Becoming a Crisis

Amid these weaknesses, the question of western lands grew increasingly urgent. Several states claimed overlapping territories stretching toward the Mississippi River. New settlers pushed into these regions, sometimes without legal authority. Violence flared between Native nations, land speculators, and frontier families. Without a strong federal government, the situation threatened to spiral into chaos. We needed a national plan that would organize these lands, settle disputes, and prevent the rise of independent western republics that might break away from the Union entirely.

The Necessity of a National Territorial Policy

It became clear that only a unified territorial system could stabilize the frontier and protect the reputation of the United States. The states needed to cede their western claims to Congress so it could establish orderly governance, regulate land sales, and ensure that settlers enjoyed the rights of American citizens. But under the Articles, Congress had limited authority to manage this enormous task. Still, we pressed forward, knowing that without structure and law, the West would grow in disorder and disunity.

The Foundation for the Northwest Ordinance

These challenges created the conditions that led me and others to craft the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. The Ordinance was more than a land policy; it was a solution to the inadequacies of the Articles. It established a clear path from unsettled territory to fully formed states, ensuring that new lands would strengthen the Union rather than fracture it. Though the Confederation Congress lacked strength in many areas, it accomplished one lasting achievement by granting the West a framework built on rights, education, and republican government. In this way, the weaknesses of the Articles taught us what a nation truly needed, guiding us toward stronger structures that would later be secured under the Constitution.

My Name is Rufus King: Statesman of the Early American Republic

I was born in 1755 in Scarborough, Massachusetts, into a family that valued education, discipline, and public virtue. My father was a prosperous farmer and merchant, and although our world was rural, the ideas of the Enlightenment and the tensions with Britain reached even us. When the colonies erupted in resistance, I was studying at Harvard, sharpening the mind that would later guide me into the nation’s political arena.

Becoming a Lawyer and Entering Public Life

After college I studied law under Theophilus Parsons, a brilliant legal mind who taught me not merely the letter of the law but its purpose. When the Revolutionary War began, I served briefly in the militia, but it became clear that my greatest strength was not on the battlefield. Massachusetts needed men who could help build a nation through argument, persuasion, and legislation. That became my calling.

At the Constitutional Convention

By 1787 I had earned a place among the delegates sent to Philadelphia to repair the failing Articles of Confederation. There, I found myself surrounded by extraordinary minds—Madison, Hamilton, Franklin. I supported a strong national government, believing that liberty needed structure, not chaos. One of my proudest moments came when I argued for banning the importation of slaves. Though the Convention compromised, it was a step toward the larger struggle.

Championing Restrictions on Slavery

My convictions against the spread of slavery defined much of my political career. When Nathan Dane proposed the clause banning slavery in the Northwest Territory, I stood firmly behind it. I saw clearly that the future of the republic depended on drawing a line—one that prevented slavery from spreading across the continent. This principle guided me again and again, whether in debates over Missouri or in my support for free-labor territories.

Service in the Senate and Abroad

President Washington appointed me as Minister to Great Britain, where I worked to stabilize fragile relations after the Revolution. Later, as a U.S. Senator from New York, I fought tirelessly for fiscal responsibility, strong national institutions, and the prevention of slavery’s expansion. I was not always the most popular man in the chamber—my speeches were sharp, and I did not soften my convictions—but I held fast to what I believed would preserve the Union.

The Missouri Crisis and My Final Years

The Missouri debate of 1819–1820 was the culmination of everything I had long feared. The nation stood on the edge of a divide, and I rose again, an aging statesman refusing to yield, warning that the extension of slavery threatened the republic’s very soul. Though the Compromise passed, I made it clear that the issue was not settled. History proved that warning true. I continued to serve New York and the nation until age and illness finally silenced my voice in 1827.

Reflections on a Nation Still Growing

As I look back, I see my life not as the story of a single man but as an early chapter in the long debate over freedom and equality in the United States. I dedicated my years to shaping a nation strong enough to endure and principled enough to improve. If future generations continue that work, then my efforts—and the struggles of my time—will not have been in vain.

Western Land Claims and Their Cession to Congress (1781–1786) – Told by King

In the years following the Revolution, our young nation faced a danger greater than any foreign enemy: the threat of internal division. Several states—most notably Virginia, New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts—claimed vast territories reaching far beyond the Appalachian Mountains. These claims overlapped one another and stretched to the Mississippi River. Meanwhile, the smaller states, such as Maryland and Delaware, possessed no such western domains. They feared that the states with large land claims would grow too powerful, leaving the others diminished and politically irrelevant. The Articles of Confederation already held us together by a fragile bond; unequal land holdings threatened to tear that bond completely.

The Strain of Conflicting Claims

These territorial disputes were not merely lines on a map. Settlers moved into these lands, creating conflicts over who had legal authority. Land companies speculated wildly, selling overlapping claims and stirring unrest. Native nations defended their homelands, leading to violence and instability. Without a strong federal government to regulate expansion, the frontier risked becoming a patchwork of competing state jurisdictions. Some feared that settlers might eventually form their own independent nations, permanently weakening the Union. We needed a solution that would place the western lands under a single, national authority.

Maryland’s Stand and the Push for Unity

The turning point came when Maryland refused to ratify the Articles of Confederation unless the land-rich states agreed to cede their claims. Maryland argued, rightly, that the war had been fought by all states and that new lands should benefit the nation as a whole. Their refusal forced the country to confront the imbalance. Reluctant at first, the larger states eventually recognized that national unity mattered more than protecting vast but ungovernable territories. If we hoped to survive as one republic, the West had to become property of the United States, not the private domain of individual states.

Virginia’s Cession and the Precedent It Set

Virginia acted first and set the crucial precedent. In 1784, it agreed to cede its enormous claims in the Ohio Valley to Congress, with the understanding that new states would be formed from the land and admitted as equals to the original thirteen. Other states soon followed, abandoning their claims and acknowledging Congress’s authority over the western territories. As a young politician, I watched this process with admiration. It revealed that even in moments of deep disagreement, we could choose compromise over conflict.

The Foundation for a More Perfect Union

The cessions transformed the nation. With the land placed under collective ownership, Congress gained its first real opportunity to govern effectively. This opened the door to the creation of the Northwest Ordinance, a document that established civil rights, public education, orderly settlement, and a path to statehood. By giving up their individual claims, the states ensured the survival of the Union and prevented the West from fracturing into competing republics. The decision to nationalize the territories was not merely a political maneuver—it was an essential step toward building a country that stretched from the Atlantic to the interior, guided by shared laws and common purpose.

My Name is Manasseh Cutler: Architect of Western Settlement

I was born in 1742 in Killingly, Connecticut, into a world shaped by hard work, faith, and the expectation that young men would serve their communities. From an early age I was drawn to study—not only theology but also science, botany, and the natural world. That curiosity led me to Yale, where I learned to see knowledge as a tool for improving society. Little did I know that this mix of scholarship and practicality would one day guide thousands of settlers into the American West.

A Minister, a Scientist, and a Doctor

Before I ever entered politics, my life was defined by service. I became a Congregational minister, preaching in the small town of Ipswich Hamlet in Massachusetts. Yet my interests stretched far beyond the pulpit. I practiced medicine, studied astronomy, and conducted experiments in botany that earned me recognition among American scientists. The people of my parish saw me not only as a preacher but as their physician, teacher, and problem-solver. These many roles taught me the value of order, discipline, and community—values I later carried into national affairs.

The Ohio Company and a New American Frontier

After the Revolution, many veterans sought new opportunities in the western lands. I joined forces with General Rufus Putnam and others to form the Ohio Company of Associates, dedicated to purchasing and settling land in the vast Northwest Territory. These men turned to me not merely for guidance but as their representative in Congress, trusting my ability to negotiate and secure favorable conditions for future settlers. I accepted the task because I believed the frontier could become a place of orderly, virtuous communities if shaped by wise laws.

Negotiating the Northwest Ordinance

My time in New York, where Congress met in 1787, became one of the most consequential periods of my life. While Nathan Dane drafted the antislavery clause and others debated land policies, I worked behind the scenes to win support for the entire Ordinance. I understood that if Congress wanted to sell land in the West, it had to guarantee stable governance, education, religious freedom, and civil rights. Through careful diplomacy, personal meetings, and political bargaining, I helped secure overwhelming approval for the Ordinance. It gave settlers a clear path from frontier territories to full statehood and ensured that the Northwest would be forever free.

Building Communities in the Northwest Territory

After the Ordinance passed, I turned my attention to helping families move west. The Ohio Company’s settlement at Marietta became the first organized American community in the Northwest Territory. I often advised these pioneers, stressing the importance of schools, churches, and laws that promoted moral character. Though I spent most of my life in New England, I took pride in watching the frontier develop into a land of free labor and democratic institutions.

Later Years of Ministry and Public Influence

In my later years, I returned to a quieter life in Ipswich. I continued preaching, studying science, and corresponding with scholars across the new nation. I also served briefly in the U.S. Congress, where I supported measures that strengthened national unity and encouraged westward expansion through lawful means. Age did not dim my curiosity or my belief that educated, virtuous citizens were the key to a healthy republic.

The Need for a Structured Territorial Policy – Told by Manasseh Cutler

In the years after the Revolution, the lands beyond the Appalachians drew countless families with the hope of fresh opportunity. Yet for all their dreams, these settlers feared what they might find. The West was a region of uncertainty—unmarked boundaries, conflicting land claims, and the constant risk of violence. People wished to build farms and communities, but without a guiding structure, they could not be sure their lands were legally theirs or that any government would protect them. I saw clearly that the frontier needed more than brave pioneers; it needed a dependable system of laws.

The Cry for Legal Protection and Order

As a minister, physician, and advocate for the Ohio Company, I spoke with many veterans and families who longed to move west. Their stories were similar. They wanted guarantees that their property would be recognized and defended; that justice would be available when disputes arose; and that the frontier would not devolve into disorder. Under the Articles of Confederation, however, Congress had limited authority to impose such protections. Without a national territorial policy, these families would take enormous risks, uncertain whether their investments or even their safety could be assured.

Preventing Chaos Through Structured Governance

The absence of structure threatened more than individual settlers—it threatened the unity of the nation itself. If families moved west into legal confusion, they might form their own systems of government, independent of the states or Congress. Frontier regions could become isolated, self-governing enclaves with little loyalty to the United States. Without the guiding hand of federal policy, the West risked developing into a patchwork of rival territories. A structured territorial system was essential if the nation hoped to maintain order and cohesion as it expanded.

A Framework for Rights and Opportunity

The people needed more than boundaries and officials; they needed assurances of their rights. They wanted schools for their children, fair courts, religious freedom, and a clear path toward self-government. Their future should not be uncertain or dependent upon the whims of distant authorities. A well-designed territorial policy would give settlers the confidence to put down roots, knowing that they lived under laws that recognized their liberty and dignity. The West could become a place of thriving communities rather than lawless outposts.

Laying the Groundwork for the Northwest Ordinance

These pressing concerns shaped my determination to help craft a lasting territorial system. The settlers’ demands for protection, property rights, and stable governance helped inspire the principles that would later appear in the Northwest Ordinance: rights of citizenship, stages of government, and a promise that new states would join the Union as equals. It was my belief that only through such a policy could the West grow with peace, virtue, and order. The frontier beckoned, but it required a firm foundation if it was to fulfill the promise of a united and prosperous nation.

Early Debates on Slavery in the Territories (Pre-1787) – Told by Rufus King

In the years following the Revolution, as the new United States began to consider how to govern its western lands, the question of slavery rose to the center of debate. We had fought a war for liberty, yet permitted an institution that denied liberty to thousands. As settlers pushed westward and territorial policies began to take shape, it became clear that the character of these new lands would determine the future moral direction of the nation. I was still a young statesman then, but I recognized early that the expansion of slavery posed a grave threat to the principles we claimed to uphold.

Uncertain Boundaries and Uncertain Laws

Before 1787, the territories had no consistent legal framework, and slavery’s status varied from region to region. Some settlers brought enslaved laborers with them, relying on old colonial laws or vague assumptions to justify their presence. Others protested that slavery had no rightful place in new territories that belonged to the nation as a whole. Without a unified policy, disputes erupted, and the lack of national authority under the Articles of Confederation left Congress unable to provide clear guidance. The frontier risked becoming a battleground of incompatible laws and clashing moral visions.

Arguments for Restricting Slavery’s Growth

Within Congress, several of us argued that the territories should be free. We saw slavery as incompatible with republican ideals and believed that once the institution took root in a region, it would shape its politics, economy, and morals for generations. I spoke often of the dangers of allowing slavery to spread unchecked, warning that the unequal distribution of enslaved labor could bring dangerous divisions among the states. If the West was to become the foundation of the nation’s future, it needed to be built on free labor and equal rights.

Resistance from Those Who Sought a Slaveholding Frontier

Not everyone agreed. Some southern delegates feared that banning slavery in the territories would weaken their political influence. Wealthy landholders believed enslaved workers were necessary for developing large tracts of land and feared that prohibiting slavery would discourage settlement. Others argued that Congress lacked the authority to interfere, insisting that settlers should be free to bring their property—including enslaved people—wherever they chose. These debates were fierce, emotional, and often deeply personal.

The Need for a Defining Policy

The early years revealed a simple truth: without clear territorial legislation, slavery’s status in the West would depend on the shifting will of settlers, judges, and state politicians. Such uncertainty was a recipe for conflict. The nation needed a decisive ruling—one that would reflect our founding ideals and preserve unity among the states. These early debates helped lay the intellectual groundwork for what would become the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, where the question of slavery would finally be addressed with clarity.

The Dawn of a Larger Struggle

Looking back, those pre-1787 debates were the first signs of a conflict that would eventually overshadow every other national issue. Many believed the matter had been settled when slavery was prohibited in the Northwest Territory, but I knew even then that the struggle was far from over. The moral divide exposed during those early discussions would continue to shape the nation’s politics, its laws, and its identity for decades to come.

Drafting the Northwest Ordinance (1787) – Told by Nathan Dane

In the summer of 1787, while delegates in Philadelphia were crafting the Constitution, the Confederation Congress faced an equally important task: establishing a government for the vast Northwest Territory. The West could not wait for a new national framework. Settlers were already pushing into the region, and conflicts over land, law, and rights demanded immediate attention. Congress needed a comprehensive policy—one that would provide structure, protect citizens, and prevent chaos. It was in this environment that I found myself shaping what would become the Northwest Ordinance.

Taking Up the Pen in a Critical Hour

The responsibility of drafting the Ordinance did not come to me through grand ceremony. Rather, circumstances placed the task before me. A committee had begun earlier versions, but none were complete or adequate. With Congress under pressure to act quickly, I stepped in to revise and refine the document. My goal was simple but ambitious: create a blueprint for territorial growth that balanced federal oversight with the promise of eventual self-government. I was determined that the new lands would become healthy extensions of the republic, not distant dependencies or regions spiraling into disorder.

Crafting Rights and Responsibilities

I believed that settlers deserved the full protections of citizenship even before statehood. With this in mind, I added provisions guaranteeing freedom of religion, the right to trial by jury, the protection of property, and the encouragement of education. These were not luxuries; they were foundations upon which virtuous communities could grow. Each section of the Ordinance was designed to provide both liberty and stability, ensuring that frontier societies would reflect the principles upon which the nation had been founded.

Writing Article 6 and Prohibiting Slavery

Perhaps the most significant moment came when I drafted Article 6, the clause banning slavery in the Northwest Territory. I knew the proposal would attract controversy, but to my surprise, it passed swiftly and with little debate. Many delegates recognized that the West must not become a battleground of conflicting labor systems. By prohibiting slavery, we drew a clear line that shaped the future of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin. It was a decision rooted not only in moral conviction but in the belief that the spread of slavery would endanger national unity.

Establishing the Path to Statehood

The Ordinance also set forth the three-stage process by which a territory could become a state. This was crucial. It prevented frontier regions from breaking away prematurely and guaranteed that new states would join the Union on equal footing with the original thirteen. The framework ensured orderly development, allowing communities to grow, organize, and eventually govern themselves. This system, once adopted, became a model for all future western territories.

Completing the Work and Seeing It Adopted

On July 13, 1787, Congress adopted the Northwest Ordinance. It passed almost unanimously—a remarkable achievement for the weak Confederation government. In the midst of national uncertainty, we had created a document that provided stability, opportunity, and a long-term vision for expansion. I did not claim credit at the time; the work belonged to the nation, not to any individual. But I knew we had accomplished something lasting.

A Foundation for America’s Future

Looking back, I see the Ordinance as one of the Confederation’s greatest achievements. It proved that even a weak Congress could act with clarity when necessity demanded it. My role in drafting the Ordinance was one of the defining efforts of my life, for it shaped the character of the American Midwest and set a precedent for the nation’s growth. It stands as one of the few moments when wisdom and urgency joined to produce a law that served both present needs and future generations.

“There Shall Be Neither Slavery Nor Involuntary Servitude”: The Anti-Slavery Clause – Told by Nathan Dane

When I drafted the Northwest Ordinance in 1787, one conviction guided me more strongly than any other: the new territories must not become strongholds of slavery. The nation was still fragile, its unity uncertain, and the institution of slavery already cast a long shadow over our politics and ideals. If the West grew under its influence, the republic might fracture before it truly began. So I wrote a simple yet profound sentence—“There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory”—with the hope that it would secure the moral and political future of the Northwest.

Anticipating Resistance and Preparing for Debate

I knew that proposing such a bold restriction could provoke strong opposition, particularly from delegates representing states where slavery was deeply woven into the economy. I expected heated debate, accusations of overreach, and perhaps even the rejection of the entire Ordinance. Yet the moment demanded clarity. The territories needed a unified labor system, and I believed deeply that free labor was the only foundation consistent with republican virtue. I prepared myself for a long struggle, certain that the clause would face resistance.

The Surprisingly Swift Acceptance

To my astonishment, the clause passed almost without debate. The Confederation Congress, weary from years of argument and anxious to bring order to the western lands, seemed ready to embrace a decisive solution. Many delegates recognized that banning slavery in the Northwest Territory would prevent future conflicts between free and slave states. Others saw practical advantages: free labor would attract settlers more interested in building stable communities than in establishing plantations. What I expected to be the most contentious part of the Ordinance instead became its most unanimously accepted feature.

Motivations Behind the Support

The support for the clause came from several directions. Some delegates agreed with me on moral grounds, believing slavery incompatible with the principles of liberty for which we had fought the Revolution. Others acted out of political calculation, hoping that a free Northwest would strengthen their region’s influence in Congress. A few simply wanted clear rules that would prevent disputes among settlers. Whatever their reasons, their collective approval turned my clause into law and set the Northwest Territory on a path distinct from the slaveholding South.

A Legal Line That Shaped the Nation

With Article 6 adopted, the Northwest Territory—comprising the future states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin—became closed to slavery. This decision shaped the social and political character of the Midwest for generations to come. At the time, none of us knew how significant this would be. But I sensed that we had drawn a boundary not just on the map but in the national conscience. Where slavery could not expand, different institutions, economies, and ideals would take root.

The Beginning of a Larger Struggle

Though the Ordinance’s anti-slavery clause stood firm, it did not resolve the deeper national conflict over slavery. Southern states grew increasingly protective of the institution, while northern states moved toward gradual abolition. The divide widened, and future generations would confront it in ways we could scarcely imagine. Yet I take some solace in knowing that the Northwest Territory began on a foundation of freedom. The clause I wrote was not merely a line of text—it was a commitment to a future where liberty might one day be extended to all.

A Legacy of Conviction and Hope

When I reflect on those days, I remain grateful that Congress recognized the wisdom of banning slavery in the Northwest. It affirmed that even in a divided nation, we could still act with principle when the moment demanded it. The clause marked one of the few clear victories for freedom in the early republic, and though it did not end slavery, it limited its spread and strengthened the hope that the United States could someday align its laws with its ideals.

Manasseh Cutler’s Political Negotiations That Secured Passage – Told by Cutler

When I traveled to New York in 1787 as the representative of the Ohio Company of Associates, I carried with me more than private interest; I carried the hopes of countless veterans and families eager to build new lives in the West. They wanted order, protection, and the assurance that their communities would rest on firm legal ground. The Northwest Ordinance promised all of this, but it required the approval of a Congress weakened by division and weary from years of political strain. My task was not only to advocate for settlers but to navigate the complex politics that surrounded the Ordinance.

Reading the Climate in Congress

I quickly discovered that many delegates were indifferent to the needs of the frontier or deeply suspicious of large land companies. Others feared that opening the Northwest too rapidly would cause disputes and destabilize the fragile union. To secure the passage of the Ordinance, I needed to understand their motivations. Some were concerned with national finances, others with regional power, and still others with preserving the spirit of the Revolution. I studied these concerns carefully, seeking points of agreement that could bring divided voices into harmony.

Uniting the Ordinance with Land Sales

The key breakthrough came when I realized that many delegates cared less about territorial governance and more about solving Congress’s financial difficulties. The government was deeply in debt and lacked the power to levy taxes. Land sales, however, offered a way to generate revenue. I made clear that the Ohio Company stood ready to purchase a large tract of land—if, and only if, Congress passed an Ordinance that provided stable governance, protected civil liberties, and prohibited slavery in the Northwest Territory. By linking the Ordinance to immediate financial relief, I transformed it from an abstract policy into a practical solution.

Building Support Through Personal Persuasion

Negotiation in Congress often occurred not in grand speeches but in quiet conversations. I met privately with delegates, appealing to their individual concerns. To some, I emphasized the economic benefits; to others, the moral importance of creating free communities; and to others still, the need for structured expansion to avoid chaos. I listened as much as I spoke, earning trust by showing that I understood the nation’s challenges. Gradually, I helped shape a coalition of supporters—men who saw the Ordinance as a rare opportunity to strengthen the Union while promoting orderly settlement.

Overcoming Resistance and Securing Agreement

There were moments when the Ordinance’s passage seemed uncertain. Some delegates resisted the anti-slavery clause; others worried that the process for statehood granted too much autonomy to frontier settlers. Yet each challenge provided an opening for negotiation. I assured skeptics that strong federal oversight would remain in the earliest stages of territorial growth, and I emphasized that banning slavery was necessary to prevent future disputes. By addressing concerns calmly and offering reasonable compromises, I helped dissolve resistance and unify support behind the final draft.

The Final Victory for the Frontier and the Nation

On July 13, 1787, Congress adopted the Northwest Ordinance with overwhelming approval. The success was a victory not only for the Ohio Company but for the entire nation. It provided a model for how new states could enter the Union as equals and established a system rooted in liberty, education, and republican virtue. My negotiations had done more than secure a land purchase; they had helped shape a policy that guided the settlement of half the nation’s territory.

A Legacy Shaped by Collaboration and Resolve

Looking back, I see that the Ordinance succeeded because it balanced vision with practicality. By linking governance to land sales, appealing to delegates’ diverse concerns, and emphasizing shared national interests, I helped build consensus at a moment when unity was desperately needed. The Northwest Ordinance stands today as a testament not only to the principles embedded within it but to the power of careful negotiation, patient persuasion, and a commitment to the greater good.

My Name is Arthur St. Clair: Governor of the Northwest Territory

I was born in 1734 in Thurso, Scotland, a land of harsh coasts and proud traditions. Though my family held modest means, I received a strong education and apprenticed briefly in medicine. Yet I felt a pull toward greater opportunity than my homeland could offer. When the chance came to serve in the British Army during the French and Indian War, I crossed the Atlantic, not knowing that North America would become my true home.

A Soldier for Britain and Then for a New Nation

My early military service took me through the brutal forests and frontier posts of the Ohio Valley. I fought under General Wolfe during the campaign for Quebec, learning both discipline and the difficulties of commanding men in unfamiliar terrain. After the war, I settled in Pennsylvania, married, and entered public life. When the American Revolution began, I chose the Patriot cause. I served as an officer in the Continental Army, eventually rising to major general. Though my command at Fort Ticonderoga ended in controversy, I devoted myself fully to the struggle for independence.

Public Service After the Revolution

After the war, I continued to serve the new republic in Congress. I presided over the Continental Congress in 1787, the same year the Constitutional Convention met. The nation was fragile, divided, and uncertain, but I believed deeply in the need for a stronger union. That belief guided me when Congress appointed me the first governor of the newly formed Northwest Territory later that year.

Building Government in the Northwest Territory

When I took office, the Northwest Territory stretched across what would become Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin. It was a land rich in potential but fraught with conflict, hardship, and political tension. My task was enormous: to implement the Northwest Ordinance, establish civil government, enforce laws, organize courts, and protect settlers while maintaining peace with Native nations. I traveled constantly, built administrative centers, and appointed local magistrates. It was an effort to create order where none existed.

War, Defeat, and Responsibility

Not all of my time as governor was marked by success. One of the darkest moments came in 1791, when I led a U.S. force against a confederation of Native nations resisting American expansion. The campaign ended in a devastating defeat, the worst suffered by the United States Army at the hands of Native warriors. It weighed heavily on me for the rest of my life. I accepted responsibility, though illness, poor supplies, and lack of support from the War Department contributed to the disaster. Despite the humiliation, I remained at my post, determined to carry out my duties.

Conflict with Territorial Settlers and My Removal

As more settlers arrived, they grew restless for statehood, especially in Ohio. My strict enforcement of territorial law and my opposition to premature admission created fierce political enemies. I believed that orderly development required patience and caution; others simply wanted quicker power. In 1802, President Jefferson removed me from office. Though I disagreed deeply with the decision, it marked the end of my political career.

Implementing the Northwest Ordinance: Rights, Schools, and Civil Liberties – Told by Arthur St. Clair

When I accepted the appointment as the first governor of the Northwest Territory, I walked into a vast region with almost no formal institutions. The Northwest Ordinance promised rights, civil liberties, and an orderly path to statehood, but promises alone could not build courts, recruit militias, or create functioning communities. My task was to transform written law into living reality. Every river settlement, every frontier cabin, and every new township depended on the structures I was responsible for building.

Establishing Courts and Upholding Justice

One of my earliest duties was to create a judicial system that could earn the trust of settlers scattered across the territory. The Ordinance guaranteed trial by jury, due process, and the protection of property. To enforce these rights, I appointed judges, established territorial courts, and ensured that each county developed a reliable system for resolving disputes. The lawless uncertainty of frontier life threatened these ideals, but step by step, we replaced confusion with order, giving settlers confidence that justice was more than a distant promise.

Raising Militias to Protect the Frontier

Security was not merely a legal matter—it was a practical necessity. Settlers faced danger from criminal elements and from violent conflicts that arose as indigenous nations resisted American encroachment. The Ordinance required that a militia be organized to keep the peace. I worked tirelessly to form, train, and equip these forces, though we often lacked resources. The militias helped enforce territorial laws, defend remote communities, and maintain stability as the population grew. Their existence reassured families that they could build lives in the Northwest without fear of constant attack or disorder.

Building Local Governments from the Ground Up

Territorial government was a three-stage process, and in those early years we were firmly in the first stage. That meant I held considerable authority, but it also meant I had great responsibility. I established townships, appointed magistrates, and guided the formation of legislative procedures. Each community needed a structure for resolving disputes, managing resources, and providing basic services. Through careful planning, we laid foundations strong enough to support more democratic institutions once the population grew.

Promoting Schools and the Education of Citizens

The Northwest Ordinance declared that “religion, morality, and knowledge” were essential to good government, and thus schools were prioritized. I encouraged townships to set aside land for public education and worked with community leaders to establish early academies. Education was not universally available on the frontier, but each school we opened strengthened the territory. Literate citizens were better prepared to serve on juries, participate in town meetings, and uphold the principles of a free society.

Safeguarding Civil Liberties in a Developing Territory

Civil liberties were the heart of the Ordinance. Freedom of religion, the right to habeas corpus, protections against cruel punishment—these rights needed constant defense. In a region where passions ran high and law was still young, abuses could easily occur. I intervened when necessary, reminded local officials of their obligations, and insisted that settlers from every background received fair treatment. These principles were not negotiable. They defined the territory’s character and ensured that the West did not become a place where liberty was sacrificed for convenience.

Guiding a Territory Toward Statehood

Though the early years were challenging, the institutions we built endured. Courts began to operate smoothly, militias maintained order, and communities saw the value of education and civic responsibility. As the population increased, the territory transitioned into its second stage of government, gaining a legislature and moving closer to statehood. These milestones proved that the Ordinance was not merely an idealistic document—it was a workable system capable of nurturing thriving American states.

Organizing the First Territorial Governments – Told by Arthur St. Clair

When I took office as governor of the Northwest Territory, the region had no officials, no legislatures, and no established legal customs beyond what settlers carried with them. Everything we built had to begin with the guidelines of the Northwest Ordinance. Those guidelines were clear, but turning them into a functioning government required patience, organization, and constant travel across vast distances. My duty was to bring order to a frontier that had only the most fragile beginnings of civil society.

The Three-Stage Process: A Blueprint for Growth

The Ordinance offered a unique framework, one unlike anything attempted before in America. In the first stage, the territory was governed by a governor and three judges appointed by Congress. Only after the population reached five thousand free male inhabitants could we enter the second stage, allowing for an elected assembly and a legislative council. Finally, when a district grew larger still and had enough stability, it could draft a constitution and apply for statehood. This three-stage process prevented sudden, chaotic shifts in power and ensured that political development grew alongside population and community readiness.

Appointing Judges and Establishing the Rule of Law

The first stage required strong judicial leadership. I appointed territorial judges carefully, choosing men who could bring fairness, legal knowledge, and stability to a land where disputes were common and emotions ran high. Together, we reviewed and adapted existing laws from the original states to suit the needs of the frontier. Courts were established in key settlements, and itinerant justices traveled to remote communities to ensure that justice was not reserved only for the well-settled towns. These early decisions set lasting precedents that shaped the territory’s legal culture.

Creating the Earliest Forms of Local Administration

Even before an elected assembly existed, we needed local structures for maintaining order. I appointed magistrates, sheriffs, clerks, and other officials responsible for keeping peace, recording deeds, and ensuring that the wheels of daily governance turned smoothly. Each new township had to understand its duties—managing roads, overseeing land distribution, and collecting necessary fees. By organizing these small units of government, we laid the groundwork for the larger political institutions that would follow.

Transitioning to Representative Government

As population grew, pressure mounted to move into the second territorial stage. Settlers desired a voice in their own governance, and many believed the time had come for an elected assembly. When reliable population counts showed that the threshold had been met, we held elections for representatives. This marked the beginning of legislative debates within the territory, where local leaders could propose laws, argue for regional concerns, and petition Congress when necessary. It was a significant moment: the territory had taken its first steps toward self-rule.

Voting Rules and the Rise of a Political Community

Establishing voting rules was a delicate matter. The Ordinance specified freehold requirements for voters, ensuring that only men with a stake in the land could cast ballots. While some settlers resented these restrictions, they were designed to promote stability and responsibility on the frontier. Elections were often lively affairs, with candidates appealing to the character and needs of scattered communities. Through these early political experiences, the settlers learned to balance local interests with the broader vision of territorial unity.

Preparing for Statehood and Long-Term Governance

With elected assemblies came new responsibilities: drafting legislation, negotiating with indigenous nations, and planning for future growth. My role shifted from direct governance to oversight, ensuring that laws aligned with the principles of the Ordinance and that the territory moved steadily toward eventual statehood. This process unfolded unevenly across the region, but each step strengthened the political identity of communities that had once been little more than isolated outposts.

First Free States Born from the Ordinance (Ohio Movement) – Told by Cutler

After the Northwest Ordinance was passed in 1787, the true test began—not in Congress, but on the frontier. A law, no matter how well crafted, means little unless it is lived out by real families. As a leader within the Ohio Company of Associates, I helped transform the Ordinance’s promises into settlement plans that ordinary men and women could follow. This was more than a migration; it was the founding of communities built on freedom, education, and lawful governance. The Ohio movement became the first demonstration of what a “free territory” could look like.

Selecting the Land and Preparing the Way

Our company purchased a vast tract at the confluence of the Muskingum and Ohio Rivers—land that would soon host the first organized American settlement in the Northwest Territory. But the selection was not made hastily. We looked for fertile fields, defensible ground, access to waterways, and room to build future towns. My role often involved translating the lofty ideals of the Ordinance into practical guidelines to help families understand where they were going and how this new society would function.

Founding Marietta: The First Free Settlement

When the first group of settlers arrived in 1788 and founded Marietta, they did so under the protections and restrictions of the Ordinance. It was the first community in American history where slavery was legally prohibited from the start. This was not an abstract victory—it shaped everyday life. Neighbors worked their own land, free labor set the rhythm of the town, and the principles of civil liberty guided local policies. Schools were quickly seen as essential, and public lots were reserved for them, signaling that knowledge and civic virtue were cornerstones of the new society.

Free Labor and the Character of the Frontier

The absence of slavery gave these early settlements a distinct identity. Without an enslaved workforce, every improvement—each road, mill, and farm—was built by the hands of the people who lived there. This encouraged cooperation and mutual respect among settlers. It attracted families who desired opportunity rather than wealth gained through the ownership of others. The free-labor system shaped the values of the region, producing a society that prized industriousness, fairness, and local participation in government.

The Ordinance Becomes a Blueprint for Statehood

As communities multiplied—Belpre, Waterford, and others—they followed the same patterns of governance: electing local officials, establishing schools, building churches, and adhering to the rights laid out in the Ordinance. These settlements were the seedlings from which future free states would grow. Ohio, the first to reach the population required for statehood, inherited not only land but also a moral framework. The values embedded in its founding shaped its laws and culture and stood as proof that a free society could flourish west of the Appalachians.

A Model for Future Expansion

The success of the Ohio movement sent a powerful message across the nation. Settlers could move west under laws that protected liberty, ensured fair treatment, and upheld education. The Northwest Territory became a model for how the United States might continue to expand—by creating communities grounded in republican principles rather than frontier lawlessness. Other territories followed the example, eventually becoming Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin, each shaped by the Ordinance’s antislavery mandate and commitment to civic development.

Early Resistance to the Slavery Ban in the Northwest Territory – Told by St. Clair

When the Northwest Ordinance declared that “there shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude” in the territory, many believed the matter settled. Yet as governor, I quickly learned that laws do not enforce themselves. The frontier was filled with men who arrived with their own expectations—some shaped by states where slavery had long existed. To them, the ban was an inconvenience, an obstacle to the labor system they thought necessary for clearing forests, planting fields, and building new communities. The tension between national law and local desire became one of the defining challenges of my administration.

Petitions Challenging the Ordinance

Almost immediately, I received petitions from settlers and local leaders who insisted that the ban on slavery hindered economic growth. Some masterfully argued that enslaved labor was essential for taming wilderness land quickly. Others claimed that the Ordinance restricted their property rights. While I understood their concerns, the law was explicit. I was bound to uphold it. Still, I could not ignore the pressure. These petitions revealed how deeply ingrained slavery was in the thinking of many who came west, even when they settled in a region designed to be free.

The Search for Loopholes and Legal Workarounds

Resistance did not always come through open protest. Some settlers attempted to bypass the law by redefining slavery under different terms. They created long-term indenture contracts intended to mimic the conditions of bondage without using the forbidden word. Others claimed that enslaved people brought into the territory before the Ordinance’s adoption should remain enslaved indefinitely. These tactics forced the territorial courts to navigate difficult questions, and my judges often struggled to balance the letter of the law with pressures from influential settlers. The ambiguity of indenture contracts became a recurring source of conflict.

Conflicts Among Settlers and Territorial Officials

These disputes did not occur in isolation. They sparked quarrels within communities and even among territorial officials. Some judges interpreted the law strictly, refusing to recognize any form of coercive labor. Others allowed loopholes to persist, believing that economic necessity justified flexible interpretation. I found myself mediating between legal principles and practical concerns, always insisting that the Ordinance’s intent—to create free territories—must not be undermined.

The Role of Migrants from Slave States

A significant source of resistance came from settlers migrating from Virginia, Kentucky, and the Carolinas. Accustomed to plantation labor systems, many believed slavery was indispensable. They brought enslaved people with them, hoping the law would not be strictly enforced. When confronted, some threatened to leave the territory entirely. These encounters revealed how commerce, culture, and personal identity were tightly bound to the institution of slavery. Enforcing the ban meant not only upholding law but challenging deeply held beliefs.

Upholding the Law Amid Constant Pressure

Despite continuous resistance, I remained committed to the Ordinance. It was not merely a territorial rule; it was a pledge that the Northwest would develop differently from regions built on bondage. I instructed judges to apply the law faithfully and reminded communities that our future states must reflect the principles upon which the Ordinance stood. Though enforcement was uneven and tensions persisted, each decision for freedom strengthened the legal foundation of the territory.

The Slow but Steady Establishment of Free Communities

Over time, as more settlers arrived from northern states and as free-labor farms proved successful, resistance began to wane. The early battles over slavery shaped the character of the Northwest Territory and laid the groundwork for the free states that would one day form the Midwest. Though the path was not smooth, the persistence of the Ordinance’s principles helped ensure that the region would grow without the institution that divided the nation elsewhere.

Rufus King’s Continued National Fight Against Slavery Expansion – Told by King

When the Northwest Ordinance established a free territory in the West, I saw more than a regional policy—I saw a precedent capable of shaping the nation’s future. It proved that Congress possessed both the authority and the moral responsibility to limit slavery in new lands. From that moment onward, I made the restriction of slavery’s expansion my central public cause. The Ordinance had drawn one clear line across the map, and I believed we must continue drawing such lines wherever new territories were formed.

Carrying the Debate into the Senate

As a United States senator, I watched the nation grapple with rapid growth. New settlements sprung up, and with them came renewed arguments over slavery’s place in expanding territories. Some claimed that climate dictated where slavery would thrive; others argued it was an issue of local choice. But I held firm to the belief that the federal government had a duty to preserve the principles we had already established. The Northwest Territory showed that free communities could flourish. Extending slavery into the West would endanger the Union and erode the very ideals of the Revolution.

Resisting the Spread of Slavery into New States

I opposed every attempt to introduce slavery into territories where Congress had the authority to legislate. Whether the debates concerned the Southwest, the Louisiana Purchase, or the lands pressing toward the Mississippi River, I spoke consistently in favor of restricting the institution. My arguments were grounded not only in morality but in the recognition that the expansion of slavery would create unbalanced political power, deepen sectional divisions, and make compromise increasingly fragile. Each new slave state shifted the balance in Congress and strained the unity of the republic.

The Missouri Crisis: A Warning Ignored

The debates over Missouri’s admission in 1819 and 1820 were the culmination of years of rising tension. When Missouri sought entry as a slave state, I warned that allowing slavery to spread beyond its existing boundaries would plant the seeds of future conflict. I argued passionately that Congress must uphold the spirit of the Northwest Ordinance and prevent the institution from crossing into the northern portion of the Louisiana Territory. Though the Missouri Compromise temporarily settled the issue, it marked the beginning of a dangerous pattern of dividing the country along geographic lines.

Why Expansion Threatened the Nation’s Soul

My opposition to slavery’s spread was rooted in a belief that the republic could not long endure half-slave and half-free. Slavery fostered inequality, undermined free labor, and created aristocratic tendencies incompatible with republican government. If the West embraced such a system, it would shape not only the region’s economy but its values, politics, and society. I believed that the future of the nation depended on forming new states grounded in the principles of liberty and industry—states that would strengthen the Union rather than draw it toward division.

The Ordinance as Proof of a Better Path

Whenever opponents questioned whether Congress had the right to restrict slavery, I pointed to the Northwest Ordinance as undeniable evidence. Its success demonstrated that Congress had exercised this authority before and that its actions had produced thriving free communities. The Ordinance was not an anomaly; it was a model. Its legacy showed that national policy could shape the character of future states and ensure that expansion did not erode the principles upon which the country was built.

A Struggle Passed to Future Generations

As my years in public service waned, I realized that the battle against slavery’s expansion would continue long after my voice fell silent. The Ordinance had set the stage, but the nation would need to decide, again and again, whether its growth would honor freedom or spread bondage. Though I did not live to see the full scope of that conflict, I remained convinced that limiting the spread of slavery was essential to preserving the Union. If future generations built upon the foundations laid by the Ordinance, then the nation still had hope for a more just and united future.

Ordinance’s Influence on the Constitution and the Bill of Rights – Told by Dane

When I drafted portions of the Northwest Ordinance in 1787, I did not know that its guarantees of liberty would soon echo in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. The Ordinance was created under the Articles of Confederation, yet it boldly declared rights that the states had not uniformly provided. We established freedoms of religion, protections for property, the right to trial by jury, and safeguards for due process. These guarantees were not decorative language; they were essential to attracting settlers to the West and ensuring that new communities would uphold the principles of a free republic.

Territorial Rights as a Model for National Liberty

The Ordinance declared that religion and morality were necessary for good government and promised that freedom of worship would be protected. It guaranteed that courts would operate fairly, that no person would be deprived of liberty or property without proper legal proceedings, and that harsh or unusual punishments would be forbidden. These rights formed the first comprehensive national statement of liberties adopted by Congress. They provided a framework that settlers experienced firsthand, long before the federal Constitution was ratified. In many ways, the territories became a testing ground for how liberty might operate in a broader national system.

Echoes of the Ordinance in the Constitutional Convention

While the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia, the Confederation Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance. The timing was no accident. The nation was in the midst of redefining itself, and the Ordinance provided a vision of orderly governance rooted in personal rights. Delegates in Philadelphia watched our work with interest. They understood that if such protections were deemed essential for new territories, they were equally necessary for the original states. The success of the Ordinance gave confidence that a written list of rights could unify diverse communities and restrain government abuses.

From Territorial Guarantees to Constitutional Principles

Many of the protections we established in the Ordinance later appeared in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. The requirement for trial by jury informed the Sixth Amendment. The ban on cruel and unusual punishments became part of the Eighth Amendment. The promise that no citizen would lose property without due process contributed to the Fifth Amendment. The Ordinance’s commitment to religious freedom anticipated the First Amendment. These similarities were not coincidence—they reflected the shared belief that freedom must be rooted in law, not left to chance.

Shaping the Character of the Early Republic

By giving settlers these rights from the moment they entered the territory, we set an expectation that all Americans—present and future—should enjoy the same privileges. The Ordinance proved that written rights could bind communities together, guide governments through uncertain beginnings, and prevent abuses of authority. When the Constitution and Bill of Rights were drafted, they drew upon this example, weaving territorial principles into the fabric of the nation. The Ordinance showed that a republic must define the liberties of its people as clearly as it defines its laws.

A Lasting Legacy in American Legal Thought

Looking back, I see the Northwest Ordinance not only as a plan for territorial growth but as a bridge between two eras of American governance. It carried the ideals of the Revolution into the legal structure of the frontier and then onward into the Constitution itself. Its protections shaped the expectations of settlers and influenced the judgments of statesmen. The Ordinance served as proof that liberty, when clearly articulated and consistently upheld, could be extended across new lands and future states. In this way, its influence will forever remain embedded in the nation’s foundational principles.

How the Northwest Ordinance Set the Stage for Future Conflict – Told by King

When the Northwest Ordinance established a free territory in 1787, the intention was to create harmony by providing a clear model for territorial growth. Yet as the nation expanded, that very clarity revealed deep differences between regions. The Ordinance drew a boundary—slavery prohibited in the Northwest, permitted in the South—which seemed at first a simple matter of governance. But as decades passed, that boundary became the foundation of intense sectional conflict. The Ordinance did not create the divide, but it illuminated it, forcing the nation to confront the question of whether freedom or slavery would shape America’s future.

The Missouri Crisis: A Test of the Ordinance’s Principles

The most dramatic moment came during the Missouri Crisis of 1819 and 1820. When Missouri applied for statehood as a slaveholding state, it threatened to extend slavery into territories where many believed it had no rightful place. I argued that Congress had both the power and the obligation to restrict slavery in new regions, just as it had done in the Northwest. The debates grew fierce, revealing a nation polarized over the very meaning of the Ordinance’s precedent. The Missouri Compromise temporarily calmed tensions, but it did so by drawing yet another geographic line—one that heightened awareness of sectional differences rather than healing them.

The Rise of Free-Soil Ideals

As settlers moved westward and new territories opened, the Northwest Ordinance became a rallying point for the emerging free-soil movement. Advocates argued that new lands should be reserved for free labor, echoing the principles first laid down in the Ordinance. They believed slavery degraded labor, corrupted politics, and threatened the economic independence of settlers. Their stance was not only moral but practical, shaped by the success of free communities in Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. The Ordinance provided proof that freedom could flourish on the frontier—fueling a political movement determined to prevent slavery from spreading west.

Growing Tensions in Congress and the Nation

The Ordinance’s clear prohibition of slavery in the Northwest meant that new free states entered the Union, shifting the balance of political power. Every free state born from the Ordinance intensified southern fears of losing influence. Each new slave state proposed in the Southwest raised northern suspicions of an aggressive slaveholding agenda. As both sides looked westward, they saw their futures at stake. The West became a symbolic battleground, with the Ordinance standing as an early marker of what was possible—and what each side feared losing.

Seeds of the Civil War Planted in Early Policy

Though no one in 1787 foresaw the Civil War, the Ordinance inadvertently planted seeds that would grow into the sectional crisis. Its antislavery provision inspired later efforts to contain slavery’s spread, while its model of territorial governance gave Congress a blueprint for shaping new states. But as the nation expanded beyond the original Northwest Territory, disagreements over how to apply the Ordinance’s principles intensified. The question shifted from “Can Congress restrict slavery?” to “Must Congress restrict slavery?” The answers divided the nation along lines that would eventually erupt into open conflict.

The Ordinance as a Lasting Symbol of a Divided Vision

To some, the Ordinance stands as a noble example of America’s capacity for principled legislation. To others, it symbolizes the earliest moment when the country acknowledged but failed to resolve its greatest contradiction. Its legacy lived on in political speeches, legislative battles, and the hearts of settlers shaping new communities. As time passed, it became increasingly clear that the Ordinance did more than organize the West—it forced the nation to confront the issue of slavery, territory by territory, decade after decade.

Comments