4. Heroes and Villains of Ancient Egypt: Relgious Beliefs of the Egyptian Civilization (3000–2000 BC)

- Historical Conquest Team

- Sep 1, 2025

- 35 min read

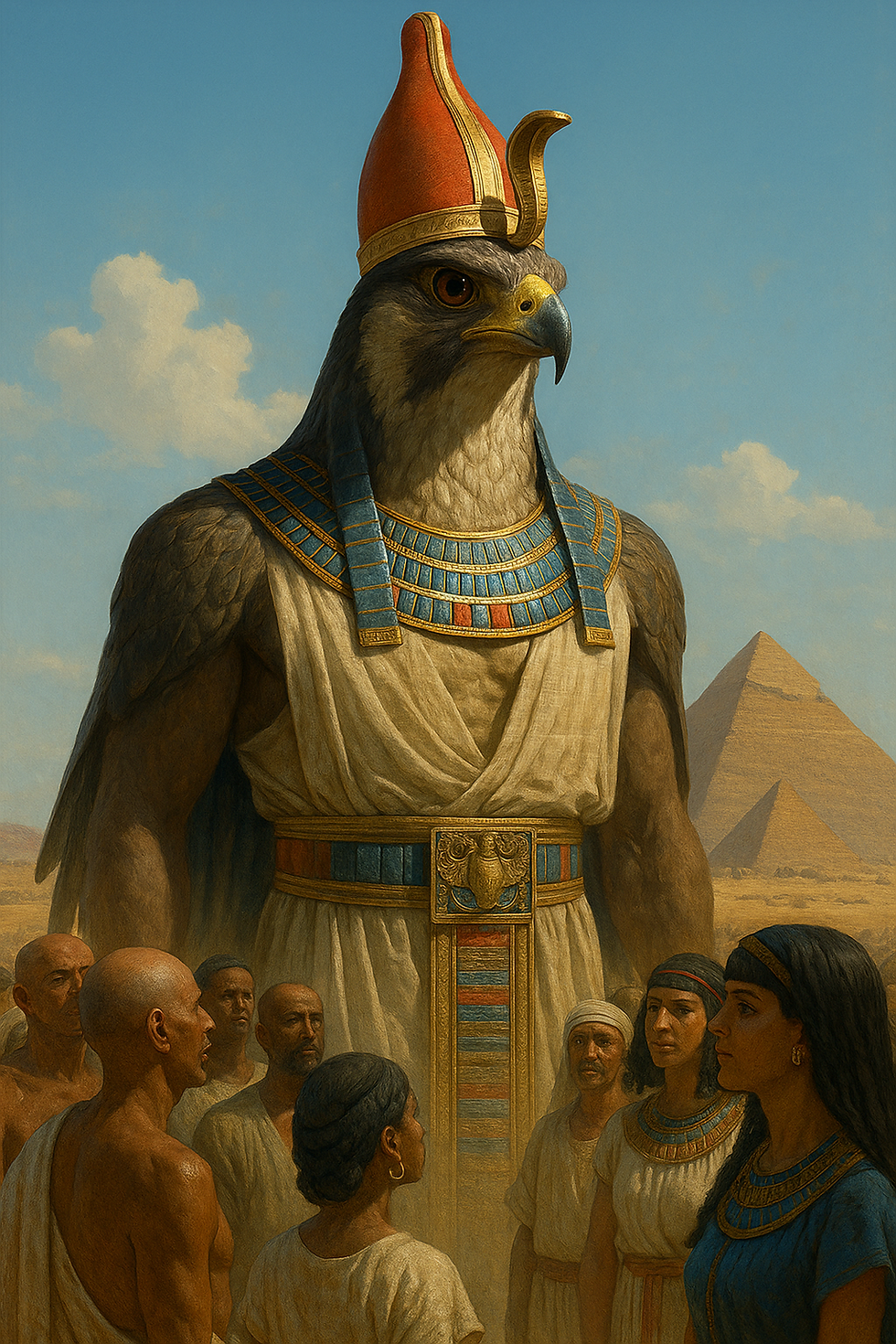

My Name is Horus: Falcon God and First King of Egypt (Mythical Figure)

I was born of Isis and Osiris, destined from the start to carry the power of the heavens upon my wings. My father was murdered by my uncle Set, and from that moment my story became one of vengeance and justice. My mother hid me in the marshes of the Nile Delta, nursing me in secrecy while Set hunted me. I grew in strength and wisdom, watched over by the gods, until I was ready to claim what was mine by birth.

The Struggle Against Set

The world was torn by conflict between chaos and order, and I was chosen to restore balance. My battles with Set raged across the land and sky. Sometimes I fought with spear and falcon’s claw, other times in the form of a great boat racing across the waters. I lost an eye in one of these struggles, but the god Thoth healed me, and my restored eye became a symbol of protection and divine vision. In defeating Set, I brought peace, though my struggle would be remembered forever in the rituals of Egypt.

The Role of Pharaoh

When I triumphed, I took my father’s throne and became the first true king of Egypt. From then on, every mortal ruler would wear my crown, for Pharaohs are but my living embodiment. They are Horus on earth, chosen to uphold ma’at, the divine order of truth and justice. With each coronation, I was reborn in human form, continuing my eternal rule over the Two Lands.

The Watcher of the Sky

I am the falcon who soars above, my wings spread wide across the heavens. My eyes are the sun and the moon, watching over all that lives. The people raise temples in my name, offering prayers and sacrifices, for they know that I guard Egypt as both god and king. The Horus falcon upon the serekh of each king’s name was not just a symbol—it was me, guiding and protecting their reign.

The Legacy of My Cult

Through me, Egyptians came to understand kingship as divine. My struggle against Set reminded them that order must be defended against chaos. My eye became their amulet, a promise of health, wholeness, and eternal protection. My name was invoked in temples, in battles, and in daily life, for I was both god of the sky and protector of the throne. In every stone carved with the falcon, in every Pharaoh crowned, my spirit endured.

The Creation Myths and the Role of the Gods – Told by Horus

In the beginning there was only the dark waters of chaos, a formless void called Nun. From this endless flood rose the first mound of earth, a small place of stability in the midst of disorder. From that sacred ground the first gods came into being, each tradition remembering them in different ways, but all agreeing that it was through their power that creation began and order was established.

The Heliopolitan Tradition

In the city of Heliopolis, it was said that Atum, the self-created one, emerged upon the mound. Alone, he brought forth the gods Shu, the air, and Tefnut, the moisture. They in turn gave birth to Geb, the earth, and Nut, the sky. From their union came Osiris, Isis, Seth, and Nephthys, the gods who shaped the destiny of the world. This lineage formed the Ennead, the great family of nine gods, whose struggles and victories laid the foundation of life, death, and kingship.

The Memphite Tradition

In Memphis, the priests taught a different story. They spoke of Ptah, the great craftsman and divine thinker. Ptah did not shape the world with hands but with thought and speech. By his heart he conceived creation, and by his tongue he brought it into existence. The mountains, the rivers, the plants, the animals, and even the other gods were fashioned through the power of his words. Thus, Memphis honored Ptah as the god of artisans and builders, for he showed that creation itself was an act of craft and design.

The Hermopolitan Tradition

In Hermopolis, it was said that eight primeval gods, the Ogdoad, first arose from the waters of Nun. They represented the hidden powers of creation: darkness and light, hiddenness and visibility, water and air, infinity and time. These eight deities stirred the waters and brought forth a cosmic egg. From this egg, the sun was born, rising for the first time and illuminating the heavens and the earth. From the light of the sun, all life came forth, and the world was filled with order and purpose.

Order from Chaos

Though the stories differ, they all teach the same truth: the world was born from chaos, and the gods gave it form and balance. They separated sky from earth, day from night, and life from death. They set the stars in motion, filled the Nile with its flood, and taught humanity to honor the divine order. I, Horus, stand as proof of their design, for through me the kings of Egypt ruled not as men alone, but as the living image of the gods who first brought light from darkness.

My Name is King Den: Pharaoh of the First Dynasty

I was born into a time when Egypt was still young, when the Two Lands—Upper and Lower—were freshly united under the crowns of my ancestors. My father, King Djet, ruled before me, and my mother, Merneith, ensured my survival and my right to the throne. When I was still a child, she guided the kingdom as regent until I was old enough to rule in my own name. From her, I inherited not only the throne but also the strength of kingship itself.

The First to Wear the Double Crown

I was the first Pharaoh to be depicted wearing the crowns of both Upper and Lower Egypt, the red and the white united upon my head. This was more than a symbol; it was proof that I held the divine right to rule both lands as one. In me, the gods Horus and Seth found balance, and through me, the people saw their protector and the keeper of ma’at, the eternal order.

Guardian of Egypt’s Borders

My reign was marked by battles at the edges of Egypt’s lands. The desert tribes pressed against us, and I led my armies to secure the boundaries of our kingdom. Victory after victory strengthened Egypt’s might, and each triumph was recorded by my officials so that the world would know the power of Horus’s chosen ruler. My image carved upon a stone shows me striking down enemies, not only as a man but as Pharaoh, the falcon’s earthly form.

A Time of Prosperity

Peace within the Nile Valley allowed Egypt to flourish. Under my rule, trade expanded to distant lands. Craftsmen shaped ivory and gold, scribes recorded the words of kings, and priests offered prayers to the gods. My palace bustled with activity, for I encouraged the growth of administration and law, binding the kingdom together with more than just soldiers. The temples of the gods stood tall, filled with offerings, for I knew that without their favor no king could endure.

My Resting Place

When my time came, I was buried in Abydos, the sacred land of Osiris, where kings were laid to rest close to the gods. My tomb stood among the earliest monuments of Pharaohs, marking my place in the eternal line of rulers. Generations after me remembered my name, and even the ancients looked back to my reign as one of strength and order. I was Horus Den, Pharaoh of the First Dynasty, the one who first wore the crowns together, and my spirit still soars with the falcon of kingship.

Kingship as a Divine Institution – Told by King Den

When I ascended the throne, I did not take on the role of a mere man ruling over other men. By placing the crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt upon my head, I became the living Horus, the falcon god in human form. The double crown was not only a symbol of unity but also a sign that the gods themselves had entrusted me with the protection of the Two Lands. To wear it was to accept the sacred duty of kingship as a divine institution.

The Pharaoh as Horus on Earth

Every Pharaoh, from my time onward, was more than flesh and blood. We were the earthly embodiment of Horus, chosen to fight against chaos and preserve balance in the world. This did not mean we abandoned our humanity, but that the gods filled us with their power, binding our fate to the well-being of Egypt. When the people looked to me, they did not see only Den, son of Djet and Merneith—they saw Horus guiding their lives, guarding their fields, and ensuring the Nile would rise in its season.

The Responsibility of Ma’at

Central to my reign was ma’at, the principle of truth, justice, and order. Without it, the world would return to the chaos from which it was born. As Pharaoh, I was charged with upholding ma’at in every decision, whether leading armies, judging disputes, or building temples. I stood as the bridge between gods and men, ensuring that offerings reached the heavens and that blessings flowed back to the earth. By honoring the gods and maintaining justice among my people, I kept the balance of creation intact.

The Divine Nature of Rule

Temples, festivals, and rituals all confirmed the sacred role of Pharaoh. Priests carried out rites in my name, for my reign was part of the cosmic order established since the time of creation. My victories in battle were not simply the triumphs of a man—they were Horus striking down the forces of disorder, protecting Egypt as he once defeated Set. My authority was rooted not in fear or conquest but in the will of the gods, who placed me upon the throne to preserve harmony in the world.

The Eternal Role of Pharaoh

Though I lived thousands of years ago, the kings who followed me continued this same divine mission. Each Pharaoh bore the titles of Horus and upheld the sacred trust of ma’at. In this way, kingship was never a matter of one man’s power, but of eternal order passed from ruler to ruler. I was King Den, Pharaoh of the First Dynasty, and my life was proof that kingship in Egypt was not merely human—it was divine, an unbroken bond between gods and men.

The Exclusivity of Pharaoh’s Afterlife – Told by King Den

In my time, the afterlife was not a promise made to all. It was I, Pharaoh, who was seen as the living Horus, and in death I was destined to become Osiris, ruler of the underworld. My soul rose with Ra, shining among the imperishable stars. This privilege was not extended to common men or even nobles, for kingship itself was the divine bridge between heaven and earth. To ensure my eternity was to ensure the survival of Egypt.

The Limits of Early Belief

Why was this gift mine alone? Some would say it was because the king alone was truly divine, chosen by the gods to uphold ma’at. Others might see it as a matter of belief not yet fully formed. In the Old Kingdom, theology had not opened the gates of eternity to all people. The rituals and Pyramid Texts were written for kings alone, inscribed in the stone chambers of our tombs, securing our passage to the heavens while others hoped only for continued existence through offerings.

The Role of the People

The destiny of the common man was tied to memory and devotion. If family brought offerings, his ka was sustained. Without them, he faded into shadow. The people understood their place as servants of Pharaoh’s eternity. By preserving my afterlife through offerings and rituals, they secured the order of the cosmos, for if the king endured, Egypt endured. Their role was not yet to join the gods, but to support the one who did.

The Opening of the Afterlife

In later times, however, this belief shifted. As dynasties passed and new writings emerged, the promise of eternity widened. The Coffin Texts gave spells not only to kings but to nobles and officials. By the Middle Kingdom, even common people began to believe they could join Osiris, becoming an akh, a radiant spirit. This democratization of the afterlife changed how Egyptians saw themselves, granting hope beyond the limits of family offerings.

The Question of Destiny

Was the exclusivity of Pharaoh’s afterlife a matter of divine truth, or simply an early stage of belief? That question endures. In my reign, it was enough to know that Pharaoh was the first among men, the one chosen to live forever as proof that the gods watched over Egypt. Yet as centuries passed, the people claimed a share in that destiny, seeing that their lives, too, were bound to Osiris. I was Den, Pharaoh of the First Dynasty, and my eternity was once mine alone—but it opened the path for all who came after me.

My Name is Ptahhotep: Vizier and Sage of the Old Kingdom

I lived during the reign of Pharaoh Djedkare Isesi of the Fifth Dynasty, a time when Egypt was strong and the sun god Ra shone brightly over our temples. I was not a king, but I held one of the highest honors a man could receive: to serve as vizier, the right hand of Pharaoh. In this position, I guided officials, judged disputes, and ensured that the will of the king was carried out with fairness and wisdom.

The Voice of Ma’at

My duty was not only to manage the affairs of Egypt but also to preserve ma’at, the balance of truth and justice that held our world together. Pharaoh embodied Horus, yet it was men like me who translated divine order into human law. I listened to disputes between farmers, advised on trade, and watched over the building of temples. Every action had to reflect the harmony decreed by the gods.

The Wisdom of Experience

As I grew older, I saw the need to pass down the lessons I had learned. Age had slowed my body, but my mind remained sharp. I composed what became known as “The Maxims of Ptahhotep,” teachings for young men who would one day hold positions of responsibility. I taught them to listen more than they spoke, to respect their elders, to treat others with kindness, and to resist arrogance. For wisdom is not in wealth or power but in humility and justice.

The Path to Eternal Life

I reminded the young that every man, no matter how mighty, returns to the earth. Only a good name and righteous deeds endure beyond death. By living in accordance with ma’at, one prepared the soul for the judgment of the gods in the afterlife. My teachings became a guide not only for officials but for all Egyptians who wished to live honorably and find peace in eternity.

My Legacy

Long after I left this world, my words were copied onto papyrus by scribes and studied in schools. Pharaohs rose and fell, dynasties shifted, but the voice of Ptahhotep was still heard. My maxims became one of Egypt’s greatest treasures of wisdom, a link between the divine order of the gods and the daily lives of men. I was Ptahhotep, vizier and sage, and through my words I still speak, guiding generations to walk the path of truth and justice.

The Concept of Ma’at – Told by Ptahhotep

In Egypt, no principle was greater than ma’at. It was truth, order, and justice woven into the fabric of the cosmos. The gods brought it forth at creation, and Pharaoh was charged to preserve it upon the earth. Yet ma’at was not only the duty of kings and priests. It lived in the choices of every man and woman. To follow ma’at was to walk in harmony with the gods, to keep one’s heart light, and to prepare the soul for eternity.

Wisdom for the Young

When age had bent my body and silvered my hair, I wrote down the lessons of my life so that the young might know the path of righteousness. I told them, “Do not be proud of your knowledge. Speak to the ignorant as well as the learned.” To honor others was to honor ma’at. Arrogance brought chaos, but humility preserved order. I reminded them that kindness and patience were not signs of weakness but the strength that kept families and kingdoms whole.

Justice in Daily Life

Ma’at was more than a word upon the lips of priests. It was the standard by which disputes were judged, lands were divided, and offerings were made. I advised officials to listen before they spoke, to weigh every matter carefully, and to rule with fairness. To mistreat the poor or favor the powerful unjustly was to offend the gods themselves. Each act of justice was a small victory for ma’at, just as every injustice threatened the balance of the world.

The Connection to the Gods

In temples, priests recited hymns to uphold ma’at. Pharaoh himself was its guardian, standing between chaos and creation. Yet even the lowest farmer who dealt honestly with his neighbor shared in that sacred duty. The gods looked not only at sacrifices of grain or gold but at the purity of the heart. To cheat, to lie, or to oppress another was to invite disorder, while to act truthfully was to strengthen the bonds between heaven and earth.

The Eternal Balance

I taught that every man must one day face the weighing of his heart against the feather of ma’at. If the heart was heavy with lies or cruelty, it was devoured, and the soul perished. But if it was light with truth and justice, the soul entered eternity. Thus, the pursuit of ma’at was both a duty in this life and the path to life everlasting. I am Ptahhotep, vizier and sage, and I say that to live in truth is to live in harmony with the order the gods themselves decreed.

The Role of Temples and Priests – Told by King Den

The Houses of the GodsIn my time, the temples stood not as palaces for men but as the eternal homes of the gods. Each one was built upon sacred ground, designed to reflect the order of creation itself. Within their walls the divine presence was made manifest. The statues enshrined in the innermost chambers were not stone alone—they were the living forms of the gods, who received offerings and gave blessings in return.

The Priests as Servants of the Divine

The priests were the hands and voices of the gods. Their duty was to purify themselves, to perform the rituals at dawn, midday, and night, and to ensure that the divine order was never broken. They washed the statues, clothed them, and offered food and drink so that the gods remained honored and strong. By their chants and prayers, they kept the connection between heaven and earth unbroken.

Centers of Ritual Life

Temples were places where festivals unfolded, where people gathered to celebrate the turning of seasons, the flooding of the Nile, and the renewal of Pharaoh’s rule. Great processions carried the gods from their sanctuaries so that the people might see them and offer their devotion. These celebrations reminded all that the gods walked among them, watching and guiding the destiny of Egypt.

Centers of Administration and Power

Yet the temples were not only spiritual homes. They were also centers of administration, where scribes kept records of offerings, lands, and workers. Granaries filled with grain and treasuries filled with gold were overseen by priests who managed the wealth given in honor of the gods. Temples supported artisans, builders, and farmers, sustaining the lives of many while reinforcing the bond between the divine and the people.

The Bond Between Pharaoh and the Gods

As Pharaoh, I stood at the heart of the temple system. The priests acted on my behalf, but it was I who was seen as the chief priest of Egypt, the one who presented the world’s offerings to the gods. In every ritual, in every sacrifice, my presence was invoked, for I was Horus on earth. By building and supporting temples, I ensured that the gods remained close to the Two Lands and that ma’at continued to govern the world.

Afterlife Beliefs: The Journey to the Duat – Told by Horus

When a man drew his last breath, his body returned to the earth, but his soul began its journey into the Duat, the mysterious realm beneath the horizon. This was not a place of endless darkness but a vast landscape of rivers, gates, and halls guarded by spirits and gods. The journey was perilous, for the soul had to overcome obstacles and prove itself worthy of reaching eternity.

The Guidance of Rituals

In the earliest times, before long scrolls of spells were placed in tombs, the soul was aided by prayers spoken by priests and the offerings given by family. The tomb itself was prepared as a home for the soul, stocked with food, drink, and possessions so that the deceased might have comfort. By honoring the body with proper rites, the living gave strength to the soul as it traveled through the Duat.

The Weighing of the Heart

At the heart of the journey lay the most important trial: the weighing of the heart. The soul stood before Osiris, lord of the underworld, and the heart was placed upon a scale against the feather of Ma’at. If the heart was heavy with lies and injustice, it was devoured by Ammit, the eater of souls, and existence ended forever. But if it was light, balanced with truth and righteousness, the soul was declared pure and allowed to pass on.

The Role of the Gods

In this trial, the gods each played their part. Thoth recorded the outcome with his pen, Anubis guided the weighing with steady hands, and I myself, Horus, brought the worthy soul before Osiris, presenting it as one who had upheld order in life. Thus, the gods did not abandon the dead but stood as witnesses and protectors in the great trial of eternity.

The Promise of Eternity

For those who were found worthy, the reward was everlasting life. They entered the Field of Reeds, a place of abundance where fields were fertile, rivers full, and families reunited. It was a vision of Egypt perfected, free from hunger, war, or sorrow. In that eternal land, the soul lived in harmony with the gods, sustained by offerings and remembrance. This was the promise given to all who walked in truth—that death was not an end but a passage into eternal order.

The Pyramid and Mortuary Cults – Told by Ptahhotep

In Egypt we did not see death as an end but as a doorway to eternity. The tomb was more than a resting place for the body; it was a house built to last forever. Its walls were carved with prayers and painted with scenes of daily life, so that the soul might continue to enjoy what it had known on earth. To prepare such a house was to honor both the living family and the gods who guarded the afterlife.

The Rise of the Pyramids

In the days of the great kings, the tombs grew into monuments of stone that touched the sky. The pyramids stood as symbols of Pharaoh’s divine power and his union with the gods. Their shape reflected the rays of the sun, guiding the king’s soul upward to join Ra in his eternal journey across the heavens. To build a pyramid was not only to honor a ruler but to preserve the order of creation itself, for Pharaoh’s eternity ensured the stability of the Two Lands.

The Mortuary Cults

Within these sacred complexes, priests tended daily rituals to feed and sustain the soul of the departed king. Offerings of bread, beer, meat, and incense were laid before the statues that carried the spirit of the dead. Each prayer and sacrifice renewed the bond between the world of the living and the eternal realm. The mortuary cult was not a single act but a continuous devotion, for the king’s soul was believed to live as long as offerings were made in his name.

The People and Eternity

Though the pyramids were built for Pharaohs, the desire for eternal life was shared by all Egyptians. Nobles raised mastabas, flat-roofed tombs adorned with carvings, while common people placed small offerings in graves so their loved ones would not hunger in the afterlife. Each according to their means sought to preserve the soul, for every heart would face judgment, and every soul desired the peace of the eternal fields.

The Balance of Glory and Faith

Thus the pyramids and the mortuary cults served two purposes: to display the glory of kingship and to fulfill the religious duty of ensuring Pharaoh’s eternal preservation. In their height and endurance, the pyramids proclaimed the power of the ruler, but in their rituals they proclaimed the truth of our faith—that through devotion, memory, and offering, the soul could endure beyond death and join the gods in everlasting life.

My Name is Sobekneferu: Pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty

I was born into the royal house of Egypt, the daughter of Pharaoh Amenemhat III, one of the greatest builders of the Middle Kingdom. I grew up within the palaces and temples, surrounded by priests, scribes, and the guardians of the gods. I was trained in the ways of the court, in governance, and in the rituals that bound kingship to the divine. Though women rarely ruled, I knew from an early age that the gods had set me apart for a greater destiny.

The Unexpected Heir

When my brother Amenemhat IV died without leaving a strong heir, the throne of Egypt stood in danger. The unity and order my father had built risked unraveling. In that moment of uncertainty, I stepped forward. The crown passed to me, and I became Pharaoh of the Two Lands. I was the first woman to bear this title openly and fully, not as a queen or consort, but as ruler in my own right.

The Power of the Crocodile God

To strengthen my reign, I bound myself to the power of Sobek, the crocodile god of strength and fertility. His might was reflected in my name—Sobekneferu, “The Beauty of Sobek.” Through him, I showed the people that my authority was divinely chosen. By honoring Sobek and the great gods of Egypt, I ruled with the protection of heaven, silencing those who doubted that a woman could sit upon the throne of Horus.

A Reign of Building and Order

During my rule, I continued the great works of my father. Temples and monuments rose, rivers were managed, and trade flowed across our borders. Though my reign was short, it was filled with effort to preserve the strength of the Twelfth Dynasty. I sought to maintain ma’at, the balance of order and justice, at a time when the future of Egypt was uncertain.

The Last of My Line

When I left this world, no heir of my father’s house remained. With my passing, the Twelfth Dynasty ended, and Egypt entered a new and troubled age. Yet my name endured, carved into stone, remembered by priests and scribes. I was Sobekneferu, the first woman to rule as Pharaoh, chosen by the gods, who proved that kingship could rest in the hands of a daughter as well as a son.

The Role of Women in Religion and Kingship – Told by Sobekneferu

In Egypt the divine was never limited to men alone. Great goddesses stood beside the gods, shaping the world with their strength. Isis, the devoted wife of Osiris, was the model of loyalty and magic, who restored her husband and protected her son Horus. Hathor, the motherly goddess, embodied love, music, and fertility, bringing joy to both the living and the dead. Neith, ancient and wise, was the goddess of war and weaving, a protector of kings and a guardian of destiny. These goddesses reminded our people that creation and power flowed through women as much as men.

Royal Women in the Sacred Order

As queens, consorts, and mothers, women of the royal house held essential places in the rituals of kingship. The king was Horus, but his mother was often seen as the earthly Isis, nurturing and protecting him. Queens joined the king in ceremonies, upheld the temples, and sometimes acted as regents when their sons were too young to rule. In these moments, their authority came not from ambition but from sacred duty, proving that women were vital in preserving both the throne and the favor of the gods.

My Own Rule

When I, Sobekneferu, rose to the throne, I did not abandon the traditions of my ancestors. I claimed my place among Pharaohs with the blessing of the gods, bearing both the titles of king and queen. My name honored Sobek, the crocodile god, but I also drew strength from the power of the great goddesses. By doing so, I showed that kingship itself was not bound to a man’s body but to the divine order, which could rest upon a woman when the gods willed it.

The Symbol of Balance

The presence of women in religion and kingship reflected the balance of creation itself. Just as Nut the sky embraced Geb the earth, just as Isis completed Osiris, so too did royal women complete the sacred harmony of Egypt. Without us, the temples would lack their fullness, and the throne would lose its strength. I, Sobekneferu, stand as proof that women were not shadows in the story of Egypt but bearers of light and guardians of ma’at.

Rituals, Festivals, and Daily Religious Practice – Told by King Den

In Egypt, the life of the people and the will of the gods were bound together by ritual. Each day, priests rose at dawn to cleanse themselves and enter the temples. They bathed, donned pure linen, and approached the sanctuary to awaken the god’s image. They washed the statue, dressed it in fine garments, and laid food and drink before it. These acts were not symbolic alone; they renewed the presence of the gods on earth and kept harmony between heaven and the Two Lands.

The Festivals of Renewal

Beyond the daily rites were great festivals that united the entire kingdom. Among the most important was the Heb-Sed, the jubilee of kingship. After thirty years of rule, Pharaoh was called to prove his strength and right to reign. In this festival, I myself once ran in ritual races, wearing the crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt, to show that my vigor remained. This was no mere display—it was the renewal of my bond with Horus, a reaffirmation that I still carried the power to uphold ma’at.

The People and Their Devotion

While the priests tended to the great temples, ordinary men and women also showed reverence in their daily lives. Families placed small offerings at shrines or in their homes, giving bread, beer, or incense to honor the gods. At festivals, the people joined processions, singing hymns and playing music as sacred statues were carried through the streets. By these acts, they felt the nearness of the divine and gave thanks for the Nile’s flood, the harvest, and the protection of their families.

The Cycle of the Year

The festivals followed the rhythm of the seasons. The coming of the Nile flood was celebrated with joy, for it meant life would return to the fields. The rising of the star Sirius marked the new year and the renewal of time itself. In these moments, the people remembered that all prosperity flowed from the gods and that Pharaoh, as their servant and protector, ensured the order of the heavens continued to bless the earth.

The Bond Between Gods and Men

Through rituals, festivals, and daily prayers, Egypt remained in harmony with the divine. These practices wove every life—whether priest, king, or farmer—into the eternal fabric of ma’at. Without them, chaos would creep back into the world. With them, balance endured. As Pharaoh, I stood at the center of this sacred rhythm, ensuring that the bond between gods and people remained strong, and that Egypt would flourish under their eternal watch.

Sacred Animals and Symbols – Told by Sobekneferu

The Crocodiles of Sobek

In my own name I carried the strength of Sobek, the crocodile god of power and fertility. To many, the crocodile was a creature of fear, gliding silently through the waters of the Nile. Yet it was also a protector, fierce and unyielding, reminding us of the strength needed to guard Egypt’s people and fields. Temples were built where live crocodiles were kept and honored, adorned with jewels as living embodiments of the god. Through Sobek, the people saw that even the might of nature itself could serve the order of the gods.

The Falcons of Horus

No symbol was more sacred to kingship than the falcon of Horus. With sharp eyes and swift wings, the falcon soared high above the earth, linking the heavens to the world below. Every Pharaoh was Horus on earth, his name written beside the falcon upon the serekh. To see a falcon circle the skies was to feel the gaze of the divine watching over the Two Lands. The falcon reminded the people that kingship itself was eternal, bound to the gods who had created order out of chaos.

The Power of Other Creatures

Yet Egypt honored many sacred animals, each chosen because it revealed a piece of divine truth. The cow of Hathor gave life and sustenance, a mother to gods and men alike. The ibis of Thoth carried wisdom, its curved beak a sign of the scribe’s pen. The jackal of Anubis guarded the necropolis, guiding souls to their judgment. These animals were not worshiped as beasts, but as vessels of divine presence, reminders that the gods walked close to their creation.

The Symbols of Eternity

Sacred animals were joined by symbols that carried their power into daily life. The Eye of Horus was worn for protection, the ankh promised life, and the scarab symbolized rebirth with each rising sun. These emblems were carved into tombs, painted on walls, and worn upon the living, weaving divine strength into every corner of existence.

The Divine in the Natural World

Through these sacred animals and symbols, the people of Egypt saw that the divine was not distant but present in the world around them. In the flight of a bird, the strike of a crocodile, or the rising of the sun, they found proof of the gods’ order. I, Sobekneferu, bore this truth in my reign, showing that kingship was not only human authority but the reflection of divine power that flowed through all creation.

Religion as the Foundation of Civilization – Told by Horus, King Den, Ptahhotep, and Sobekneferu

The Gift of Order – Told by Horus: From the moment the gods drew the world out of chaos, religion became the heartbeat of Egypt. I, Horus, gave the kingship to Pharaoh so that ma’at would endure in the land. Every temple, every offering, every festival was a reflection of that eternal balance. Without the gods, law would be meaningless, power would be hollow, and the Nile’s flood would lose its purpose. Religion was not apart from life—it was life itself, binding creation to its divine origin.

The King and the Divine Duty – Told by King Den: As Pharaoh, I carried the weight of religion in my crown. The double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt was not only a mark of my authority but proof that the gods had chosen me as their vessel on earth. Government and law flowed from this truth. My judgments were not my own but acts of Horus, protecting the weak, punishing injustice, and ensuring that offerings to the gods never ceased. Even my victories in battle were seen as divine acts, for religion gave kingship its strength and legitimacy.

The Morality of Ma’at – Told by Ptahhotep: To govern wisely, one must first live according to ma’at. Truth, justice, and harmony were the pillars of our society, and these values came directly from the gods. I taught young men to speak gently, to listen before acting, and to treat others with fairness, for morality was inseparable from religion. In the scribal schools and the courts of justice, in the fields and the markets, the measure of all things was whether they upheld ma’at. Without this divine standard, the kingdom itself would collapse.

The Sacred in Art and Architecture – Told by Sobekneferu: Religion shaped the monuments of Egypt as much as it shaped its laws. The pyramids rose as stairways to heaven, temples were built as eternal homes for the gods, and statues were carved not to honor men alone but to embody divine power. Even the simplest amulet worn by a farmer carried the promise of eternity. Art and architecture were offerings in stone, paint, and gold, binding the people to the gods through beauty and devotion. Religion was not confined to temples but lived in every carving, every wall painting, and every sacred symbol.

The Unity of Egypt – Told by All: From the beginning to the end of the age, religion wove the Two Lands together. It ordered the government, guided the law, inspired the arts, and gave meaning to life and death. Whether in the grand rituals of Pharaoh or the humble prayers of a family before a small shrine, all were united by the same truth—that Egypt’s greatness rested on the favor of the gods. It was this faith that allowed the kingdom to endure, that bound generations together, and that made religion the true foundation of our civilization.

The Gods of Egypt and Their Significance – Told by Horus

Atum, the First Creator

At the dawn of time, Atum rose from the waters of Nun, standing upon the first mound of earth. From himself he brought forth the first gods, shaping the world through his children Shu and Tefnut. To the people, Atum was the beginning of all things, the god who showed that creation itself was born from unity and will. His presence reminded Egyptians that life had a divine origin and that every generation was tied to the first act of creation.

Ra, the Sun God

Ra, the great sun, was the light that ruled over heaven and earth. Each day he sailed his boat across the sky, bringing warmth, life, and growth. Each night he journeyed through the Duat, defeating chaos so that dawn would return. The people turned their faces to him with every sunrise, for he was the giver of food, health, and the measure of time. Pharaohs were seen as his sons, continuing his strength on earth, and temples rose across Egypt to honor his eternal journey.

Osiris, Lord of the Dead

Osiris, once a king among gods, became the ruler of the afterlife after being slain by my uncle Set. He was the god of death, resurrection, and renewal, the one who judged the hearts of men. To the people, Osiris was a promise that death was not an end but a passage to eternity. Through the annual flooding of the Nile, which brought new life to the fields, the people saw the power of Osiris reflected in the rebirth of the land.

Isis, Mother and Protector

My mother, Isis, was a goddess of magic, devotion, and protection. She used her wisdom and power to restore Osiris and to guard me when I was a child. To the people, she was the model of a loving mother, the one who stood by her family with strength and cunning. Women called upon her in childbirth, rulers honored her in rituals of power, and priests invoked her spells to heal and protect. Isis embodied loyalty and the triumph of love over despair.

Seth, Lord of Chaos

Though feared, Seth was also honored as the god of the desert, storms, and foreign lands. He was a reminder of the dangers that surrounded Egypt, yet also of the strength needed to face them. To dismiss him entirely was impossible, for he was part of creation itself. In my own battles with him, the people saw the struggle between order and chaos, a struggle that echoed in their own lives. Seth’s presence warned them that vigilance and devotion were required to preserve harmony.

Hathor, Lady of Joy

Hathor was a goddess of love, music, beauty, and motherhood. She brought joy to festivals, comforted the weary, and guided the dead to Osiris. To the people, she was a gentle presence in their daily lives, a goddess who made life not only endurable but sweet. Her temples rang with music and dance, and her image was carved into jewelry and amulets carried by men and women alike.

Thoth, the God of Wisdom

Thoth, the ibis-headed god, was the keeper of knowledge, the scribe of the gods. He recorded the judgment of souls, guided the priests in rituals, and measured time and the heavens. To the people, he represented the value of learning, writing, and truth. Scribes, who carried the wisdom of the kingdom, looked to him as their divine guide. Without Thoth, order would falter, for words and records held the kingdom together.

The Balance of the Gods

Each of these gods held a place in the order of the world, just as every star has its place in the night sky. They were not distant but near, living among the people through temples, festivals, and daily prayers. Their significance was not only in their power but in the lessons they taught—of creation, justice, devotion, love, and balance. I, Horus, son of Isis and Osiris, carried their will upon the throne, proving that the strength of Egypt was bound to the presence of its gods.

The Nature of Polytheism versus Unity – Told by Horus

In the days of my people, temples rose to countless gods. Ra carried the sun across the sky, Osiris ruled the underworld, Hathor gave joy and fertility, Thoth guided wisdom and writing, and I myself guarded kingship. To the eyes of the people, these gods were distinct, each with a form, a temple, and a priesthood. Daily offerings, festivals, and prayers were directed to them as separate divine beings, close to the lives of those who worshiped.

The Hidden Unity

Yet within the temples, among priests and philosophers, there grew the thought that these gods were not entirely separate, but different manifestations of one divine source. In Memphis, Ptah was said to create all gods through his heart and tongue. In Thebes, Amun was the “hidden one” who gave power to every other deity. Even Ra, the great sun god, was linked with Atum and Khepri, showing that a single divine force could appear in many forms.

The Question of Monotheism

Was this unity something that all Egyptians believed? For the common farmer or craftsman, it was simpler to honor the god who protected his town or family. He might pray to Hathor for children or to Sobek for safety on the Nile, without troubling himself over whether they were one or many. But among the priests, the idea of a deeper unity grew strong. They saw that the divine might be one great power expressed through countless faces, a truth too vast for ordinary people to grasp fully.

The Balance of Belief

Thus Egypt lived in both worlds. To the people, religion was richly polytheistic, filled with gods and goddesses who touched every part of life. To the wise, it was also a mystery of unity, where many gods were but rays of a single light. Neither belief cancelled the other, for Egyptians were content to hold many truths at once. In my falcon form, I was Horus, yet in my kingship I was one with Ra, one with Osiris, and one with the eternal order.

The Eternal MysterySo the question remains: was Egypt moving toward one god or forever faithful to many? The truth lies in between. The divine was understood as many so that each person could see and worship a god close to their needs, yet also as one so that creation itself remained whole. I, Horus, say this is the mystery of Egyptian faith—that the gods were many in name, yet one in essence, a unity hidden within diversity.

The Gods as Aspects of One Divine Power – Told by Horus

The Many Faces of the Divine

The people of Egypt called upon many gods, yet in truth, they often understood these deities as different faces of a single divine power. When Atum rose from the waters to create the world, his essence unfolded into Shu, Tefnut, Geb, and Nut. Each was distinct, yet all were part of his being. To worship one was to honor a fragment of the greater whole. This belief allowed the people to embrace many gods while still sensing unity beneath the surface.

The Sun as the Great Example

Consider Ra, the sun god. He was worshiped under many names and forms: Khepri as the rising sun, Ra at midday, and Atum as the setting sun. Though people spoke of three gods, they were truly honoring one divine power revealed through different moments of the day. In this way, Egyptians saw the many as reflections of the one, different aspects of a single eternal force.

The Union of Gods

Temples across Egypt spoke of gods merging with others to reveal deeper truths. In Memphis, Ptah was praised as the mind and speech that created all gods. In Thebes, Amun was honored as “the hidden one” who became Amun-Ra, the unseen power behind the sun. These teachings show that even when names and forms multiplied, priests taught that the divine was one, expressing itself through many images so that humanity could grasp its mysteries.

The Human Need for Images

The people required forms to understand the unseen. The falcon revealed my power as the sky and kingship, the crocodile revealed Sobek’s strength, and the cow revealed Hathor’s nurture. Each image was a teaching tool, a way to embody what could not be easily spoken. Yet the wise knew that these were not separate gods fighting for dominion, but symbols of a single divine order, vast and incomprehensible.

The Unity Behind Diversity

Thus, some believed that the multitude of Egyptian gods were not rivals but manifestations of one god’s characteristics—strength, wisdom, fertility, justice, and love—woven together in harmony. This idea allowed Egyptians to honor many deities while never losing sight of the greater unity of creation. I, Horus, stand as one form of that eternal power, a guardian of kingship and order, but not separate from the whole. To see the gods as many is to see the colors of the rainbow; to see them as one is to understand the light from which they all arise.

The Ethics of Eternal Preservation – Told by Ptahhotep

In my age, the kings and nobles built great monuments to house their dead. The pyramids rose like mountains of stone, and vast tombs were filled with treasures, food, and images carved to serve the soul forever. These acts were expressions of faith, for they sought to preserve the body and spirit so the deceased might live eternally among the gods. Yet they were also symbols of power, declaring that the rulers of Egypt would not be forgotten.

The Burden of Wealth

But such devotion demanded great resources. Thousands labored to cut stone, to paint walls, and to prepare offerings. For the rich, eternity was secured by priests who performed rituals and by families who kept the cult of the dead alive. For the poor, there were no treasures to fill tombs, only small graves with humble offerings. This revealed a tension—did the gods judge by wealth and monuments, or by the truth in the heart?

Faith Beyond Riches

I taught that arrogance and greed led only to ruin, while humility and righteousness brought harmony with ma’at. Many among the poor still believed they could share in eternity, even without wealth, because the gods saw the heart and not the tomb. Families placed bread and beer in simple offerings, or whispered prayers to Osiris. Though they could not afford great rituals, they trusted that living in truth and justice would weigh more than gold upon the scales.

The Controversy of Inequality

This difference raised questions in our society. Was eternal life the privilege of kings and nobles who could afford grand tombs and endless sacrifices? Or was it the right of all who walked in ma’at? In truth, the practices of religion often favored the powerful, but the spirit of our teachings pointed to justice. Over time, this spirit prevailed, and the afterlife became a hope for all Egyptians, not only the mighty.

The Lasting Lesson

The grandeur of tombs and the simplicity of small graves both reveal the same truth: that men sought eternity in whatever way they could. Wealth gave voice to devotion in stone, but faith and righteousness gave voice in the heart. I, Ptahhotep, remind you that the gods look not at riches, but at justice, kindness, and truth. In this lies the true preservation of the soul, which neither time nor poverty can erase.

The Problem of Evil and Chaos – Told by Horus

From the first moment of creation, when Atum rose from the waters of Nun, the gods set the world into balance under ma’at. Truth, justice, and harmony became the order that sustained life. Yet always, at the edges of creation, lurked isfet—chaos, disorder, and destruction. I know this struggle well, for my own life was spent in battle against my uncle Set, who embodied this chaos. The Egyptians saw in our conflict a truth that never ended: order could be established, but it was never safe from challenge.

The Cause of Suffering

When floods came too high or too low, when famine spread through the land, or when enemies pressed upon Egypt’s borders, the people asked why the gods allowed such suffering if ma’at was eternal. The answer was found in the nature of balance itself. Just as the sun must set to rise again, so must order be tested by chaos. Suffering was not a sign that the gods had abandoned Egypt, but that the struggle against isfet continued and demanded renewed devotion.

The Role of Humanity

Pharaoh and the priests were tasked with pushing back the darkness through rituals, offerings, and festivals that reaffirmed ma’at. Ordinary people also bore responsibility, for each act of honesty, kindness, or justice strengthened order, while deceit and cruelty gave strength to isfet. The world was not held in balance by the gods alone but required human faithfulness to the laws of truth. Thus, the struggle against evil was not distant—it lived in every household, every field, every heart.

Foreigners and Chaos

When foreign invaders came, Egyptians often saw them as instruments of isfet. Yet even they had their place in the greater design. My own foe, Set, though a bringer of violence, was also a protector of Ra’s solar boat as it passed through the night. In this way, chaos was not always destruction alone but also a force that, when controlled, could be turned to protect order. The challenge lay in mastering it, not allowing it to master us.

The Lesson of Balance

The problem of evil and chaos has no single answer, for it is a mystery at the heart of creation. To live in Egypt was to understand that the world was fragile, suspended between harmony and disorder. Suffering came because isfet was never fully defeated, only resisted day by day. My life as Horus shows this truth: I did not destroy Set forever, but I bound him so that order could continue. So it is with the world. The people must always choose ma’at, knowing that in doing so, they join the gods in the eternal struggle against chaos.

A Comparison Between Egyptian Religion and Christianity – Told by Horus

In the days of Egypt’s beginnings, the people saw the world as filled with many gods, each carrying a piece of creation’s power. Atum shaped the cosmos, Ra carried the sun across the sky, and Osiris ruled the afterlife. I, Horus, stood as protector of kingship, ensuring that order was preserved on earth. Christianity, however, would later teach that there is only one God, eternal and all-powerful, who created and rules over everything. Where Egyptians saw a family of gods with different roles, Christians see a single divine presence guiding all.

Life After Death

The Egyptians believed death was a passage into the Duat, where the soul would face judgment before Osiris. The heart was weighed against the feather of ma’at, and if found pure, the soul entered the Field of Reeds, a paradise where life continued in perfection. Christianity, too, speaks of judgment after death, but it teaches that the soul is judged by God through faith in Christ. Those found righteous enter heaven, while those who are not are separated from God. Both faiths hold that the soul’s destiny depends on how one lived in truth and obedience.

The Role of a Savior

In Egyptian belief, Osiris was slain and resurrected, becoming the ruler of the underworld and the hope of eternal life for all who followed him. His story was one of death conquered through divine power. Christianity teaches of Jesus Christ, who died and was resurrected to bring salvation to humanity. In both traditions, a god’s death and triumph over mortality open the way for the faithful to live forever. The forms are different, but the message of renewal and eternal life is shared.

Law and Morality

For Egyptians, ma’at was the foundation of morality—truth, balance, and justice guided daily life and the judgment of the soul. To live in ma’at was to live in harmony with the gods. In Christianity, God’s commandments and the teachings of Christ provide the moral law. Love, truth, and justice form the heart of this path. Both systems teach that righteousness is more than ritual; it is a way of life that shapes one’s eternal fate.

The Human and the Divine

Pharaoh in Egypt was both man and god, the living Horus who upheld order on earth. In Christianity, no human is worshiped as divine, yet Jesus, who lived as a man, is believed to be fully God. Both traditions show the divine stepping into human life, but where Egypt made kings a bridge between people and gods, Christianity speaks of one mediator who unites all humanity with the Creator.

Eternal Truths

Though separated by time and belief, Egyptian religion and Christianity both sought to answer the greatest questions of existence: Why are we here, how should we live, and what awaits us after death? They offered hope, demanded righteousness, and bound their people together with faith. I, Horus, see in both paths the same longing of humanity—to find order in the chaos, to live in truth, and to reach for eternity beyond the grave.

Comments