2. Heroes and Villains of the Indus Valley - Neolithic and Early Settlements (e.g., Mehrgarh)

- Historical Conquest Team

- May 23, 2025

- 33 min read

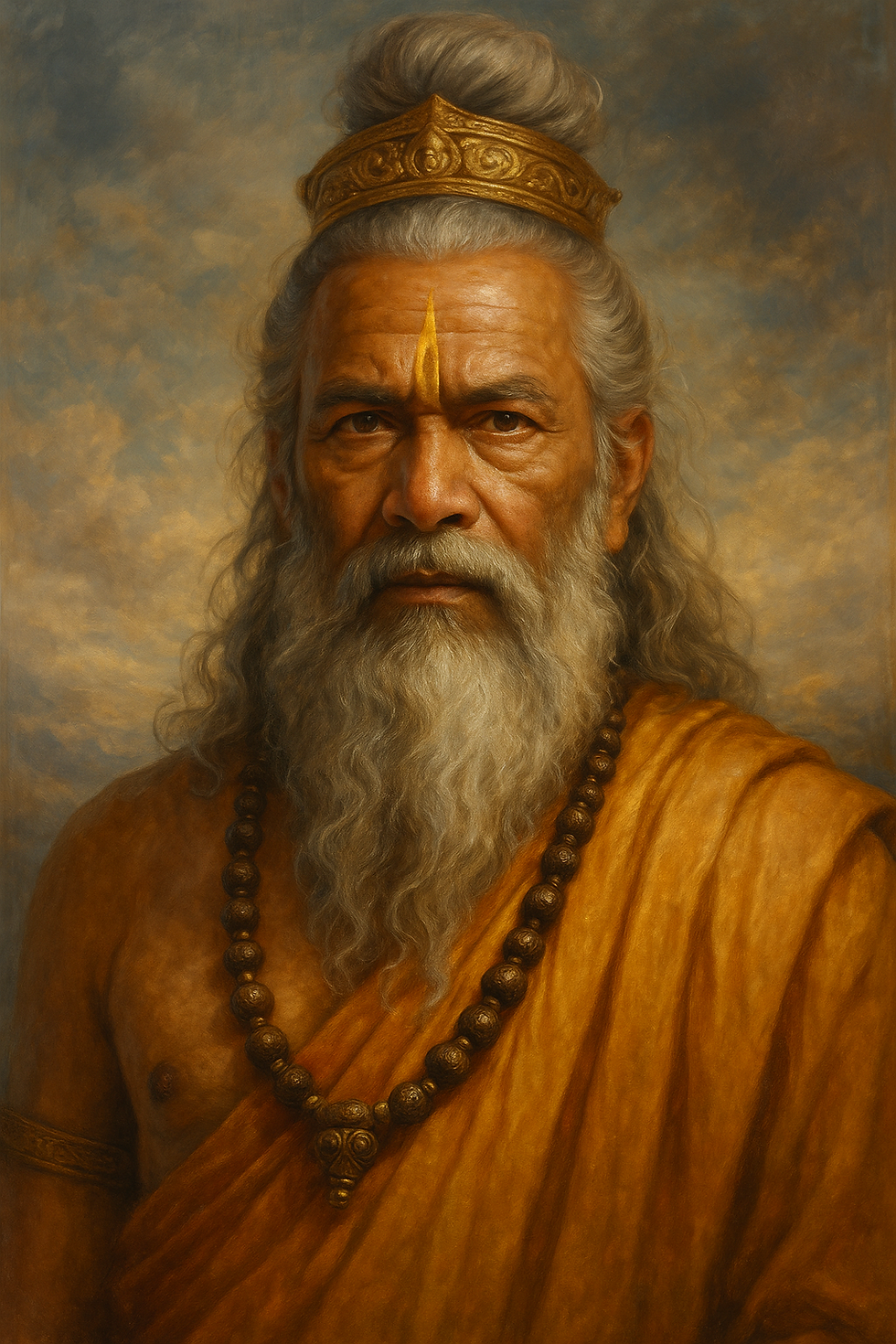

My Name is Kush (c. 2000-1500 BC): Born of Brahma’s Thought

I am Kusha, not born of womb, but of will—created from the mind of Brahma, the great Creator himself. At least that is how the legends tell it. In those ancient days, when time still moved with the rhythm of hymns and silence echoed through forests, Brahma – my god - shaped me as one of his many sons. From the moment I emerged, I carried within me the essence of balance—of wisdom and strength, of austerity and royal command. I was destined to guide humanity through both kingship and righteousness. Unlike others who rose through birthright or conquest, I came into the world already charged with sacred purpose.

Establishing the Line of Dharma

Brahma gave me land to rule and duties to uphold. I was to show the world how a king should live—not just as a wielder of power, but as a guardian of dharma. I built a kingdom where sages walked freely and where people lived in harmony with nature, gods, and one another. My rule was firm but just. I did not raise my voice unless needed, and I never raised my sword without cause. I spent as much time in meditation and counsel with learned Brahmins as I did in court. I believed that a true ruler was not above his people, but among them.

The Teaching of My Sons

In time, I fathered sons of great promise. Among them was Kushanabha, who carried forward my ideals with even greater gentleness. I taught him not just the duties of a king, but the deeper truths that cannot be seen—how to govern with compassion, how to endure loss with dignity, and how to place the welfare of others above the pride of kingship. I watched him with pride as he grew into a ruler of his own land, founding Kanyakubja and creating a haven for truth and virtue. My legacy was not one of conquest, but of cultivation—of souls, of cities, of ideas.

A Life Between Sage and King

Though I ruled as a king, I lived as a rishi in spirit. I wore simple robes when I visited the ashrams. I listened more than I spoke. I fasted in the forests and made offerings to Agni with my own hands. Some called me a rajarshi—a king-sage—for I had not renounced the world, but I had mastered it. Even the gods showed respect to those who walked the path of humility, and I sought no praise beyond the peace of a well-ordered land and the happiness of those under my care.

My Place in the Line of Light

Through my son Kushanabha, and his son Gadhi, and Gadhi’s son Vishvamitra, my lineage grew into a beacon of greatness. What began as a creation of thought became a chain of deeds that would shake the heavens. I did not live to see my great-grandson’s rise, but I knew from the signs that he would break the boundaries between warrior and sage. He would walk a path I had only glimpsed.

What I Leave Behind

I leave behind no epics sung of war, no monuments carved from stone. But I leave a legacy etched into the lives of those who came after me. I taught that the soul of a king must be as still as a sage’s mind, and that true greatness comes not from ruling others, but from ruling oneself. I am Kusha, born of Brahma’s will, father of a line that would shape dharma for ages to come. And though my name is now spoken softly, its roots run deep, feeding the tree of wisdom that still stands in the heart of Bharat.

Time Before My Time (Pre-Neolithic Era of the Indus Valley Area) – Told by Kush

Long before I walked the sacred land, before kings wore crowns and sages spoke the Vedas, the land of Sapta Sindhu—the region you now call the Indus Valley—was wild and waiting. It was shaped not by hands but by rivers. The Sarasvati, Sindhu, and their countless sisters carved paths through earth and stone, bringing life wherever they flowed. Before men settled here, before even the rituals were spoken, the land was home to whispering grasses, beasts of all kinds, and the winds of time. But even in that quiet, the seeds of civilization stirred.

The First to Roam

The first people who came to this land did not build cities or chant mantras. They were wanderers—hunters who followed the deer, gatherers who knew the secret paths of roots and fruits. They made no temples, but they lived close to the divine, though they did not know it. Their tools were of stone, their homes made of brush and earth, and their speech was soft and simple. Yet, in their silent gazes and careful footsteps, they listened to the pulse of the land, learning where the rains would fall and where the fish would swim.

The Coming of Fire and Stone

In time, they grew. They discovered fire not as a wild beast to fear, but as a companion to warm them, cook their meals, and light their nights. They shaped flint and chert into blades. They found caves in the Aravallis and the northwestern hills. Some carved stones into beads and buried their kin with care, as if knowing that life stretched beyond this world. Even then, before my time, there were signs of belief—not in gods yet named, but in forces greater than themselves. They were not yet priests or kings, but they laid the foundation of what we would one day become.

When Grains Replaced the Hunt

Then came the great change. People began to sow the earth. They planted barley and wheat in the highlands of the Baluch hills, near Mehrgarh, though that name had not yet been given. They gathered animals—goats, cattle, and sheep—and learned to live not by chasing the wild, but by cultivating the tame. Villages rose like stars across the land—small, humble, but growing. Pottery spun on slow wheels, and homes of mud-brick appeared like prayers pressed into earth. They were not yet cities, but they were the bones of future greatness.

The First Spirits of the Land

Though they had no idols of stone or temples of carved wood, they began to sense the sacred. They buried their dead with beads and tools. They painted their pots with flowing lines and perhaps told stories by firelight. They may have seen gods in the rivers, in trees, in animals. Their world was not silent—it was alive. I believe they spoke with the sky in their dreams, just as I would come to speak with Brahma in mine. They did not call upon Agni, Vayu, or Indra by name—but they surely knew the wind, the flame, and the storm as living powers.

My Reflection on Their Spirit

I did not walk among them, but I carry their memory in my bones. When I built my kingdom, I walked where their fires once burned. Their spirit lives on in the rhythms of the soil and the songs of our sages. They were not yet called Arya, nor did they sing the hymns of the Vedas—but their hands shaped the land where those hymns would one day rise. I, Kusha, born of divine thought, see now that even before the sages and kings, there were those who whispered to the earth and listened in silence. Without their steps, mine could never have followed.

The Dawn of the Neolithic (Time of Gathering into Villages) – Told by Kush

Before thrones were carved or temples raised there was a great change the overtook these people. The world was transitioning. The rivers were gentle, the rains more frequent, and the earth, soft and rich with promise. This was the Neolithic Era, known to sages and historians as the New Stone Age. Across the wide face of the world, from the valleys of Mesopotamia to the shores of China, and yes, in our own sacred land near the Indus and Bolan rivers, humans began to change the very rhythm of life. This age, beginning around 7000 BC and slowly evolving over millennia until around 2500 BC, was not marked by conquests or great cities, but by a deeper revolution—the settling of man upon the earth.

From Wanderers to Dwellers

Before this age, humans roamed. They followed the migrations of beasts, slept beneath the open sky, and lived from day to day. But slowly, in places where water was steady and the soil generous, they began to stay. In the lands of Mehrgarh and beyond, they planted barley and wheat. They learned that seeds, once scattered, could rise and feed many. They tamed animals—first sheep and goats, then cattle—and discovered the rhythms of domestication. With this came the hearth, the home, and the village. No longer did humans live in fleeting camps; they built walls of mud-brick and lived in kinship from birth to death in one place. It was a time of beginning.

The Rise of New Tools and Ways

New tools emerged from the hands of these early settlers. They polished their stones, shaped grinding stones for grain, carved sickles to harvest fields, and fashioned awls and needles from bone. Their pottery, once plain, became purposeful—storage jars for surplus grain, cooking pots for shared meals. With fire under control, clay hardened into vessels that told of a people's ingenuity. With time, the plow would follow, but even in these early centuries, the Neolithic people learned to work with the land rather than chase its bounty. It was a quiet transformation, but profound.

A Land Blessed by Rivers and Rain

In my land—the land where my descendants would rule and sages would chant—the climate offered its own gifts. The great Indus flowed steadily from the mountains, joined by countless tributaries. The Bolan River, though seasonal, carried life into the highlands near Mehrgarh. These waters, combined with monsoon rains, made the soil along the riverbanks dark and fertile. Plains once scattered with brush became places of cultivation. People learned to read the seasons and built granaries to survive the dry months. Where nature was generous, man found the will to settle and thrive.

My Reflection on Their Legacy

Though I, Kusha, lived long after this Neolithic awakening, I feel their spirit as surely as I feel the wind upon my face. These early people, nameless and humble, were the true founders of civilization. Without them, without their quiet experiments in agriculture, their shaping of tools, their courage to settle in one place, the kingdoms of my sons and grandsons would never have come to be. They began the conversation with the land. We only answered it more loudly. And so, I honor them not with monuments, but with remembrance. They were the first to root themselves in the earth—and from them, all else grew.

The Shape of Their Settlements (Early Settlers and Daily Life) – Told by Kush

In the fertile lands near the rivers, the early settlers of the Neolithic age laid down the first roots of human dwelling. Their homes were not grand palaces or painted temples, but modest structures made of mud-brick—sun-dried, shaped by hand, and stacked with care. These houses were often rectangular, with flat roofs and small courtyards where life unfolded under the sun. Beneath the earth, they dug storage pits lined with plaster or stone, where they could keep grain dry and safe from pests. A village might consist of a few dozen homes, often built close together for protection and kinship, forming a loose circle or grid. Each home was a world unto itself, yet connected to the larger life of the community.

Living Among Their Kin

Their society was built not on law, but on lineage. Blood ties and kinship guided every choice—marriage, work, inheritance, and worship. Families lived together, perhaps with grandparents, children, and cousins under the same roof or clustered in nearby homes. The elders led with experience, and the young learned by watching and doing. Roles were shared and seasonal. Women ground grain, tended hearths, raised children. Men herded animals, shaped tools, and watched the skies for signs of rain. There were hints, even then, that some tasks or roles earned greater respect. A skilled potter or a healer might hold quiet influence. Over time, as surplus grew and goods were stored, some families may have gathered more wealth than others. Here, in these early villages, we see the faint lines of what would become social layers—status shaped not by decree, but by need, skill, and legacy.

Honoring the Dead and the Beyond

When a loved one passed on, they were not simply left to the earth—they were honored. Some were buried beneath the floors of their homes, keeping them close. Others were laid to rest just outside the village, in shallow pits. Alongside them were tokens of memory and perhaps hope—necklaces of beads, pots of food, stone tools, and shell ornaments. These were not mere possessions, but signs of belief. The people sensed that life did not end with breath. They may not have spoken the names of the gods I know, but they knew of something greater—an unseen journey beyond. The presence of richer grave goods in some burials hints at early distinctions among the dead, as well as among the living. Perhaps a respected elder, a skilled artisan, or a tribal leader was given more in death, reflecting a life of meaning. These early burial patterns whisper of reverence, remembrance, and an emerging sense of status and spirit.

My Thoughts on Their Quiet Greatness

These were not my people, but they were my forebears. They lived without the pride of kingdoms or the chants of priests, yet they carried the essence of what would one day become our civilization. In their homes of mud and their humble rituals, they laid the foundation upon which my lineage would rise. Their lives were simple, but not empty. They held knowledge passed from hand to hand, wisdom not written but lived. And so I remember them—not with monuments of stone, but with words shaped by the fire of gratitude. For without their steady steps, my own would never have touched the earth.

My Name is Kushanabha (Son of Kusha): My Ancestry and Divine Birth

I am Kushanabha, born of the illustrious lineage of Kusha, the mind-born son of Brahma, the Creator. My father, Kusha, was a king and sage, one of those rare beings who carried both the sword and the staff with equal mastery. From him I inherited not just a kingdom but a sense of balance—a reverence for the divine, a respect for righteousness, and a duty to uplift the world. My birth was not ordinary. I came into the world during a time when kings were expected to live as protectors, sages, and guides. I was raised with the wisdom of the Vedas and the strength of warriors. As a child, I was taught that power meant nothing if it did not serve dharma.

The Founding of Kanyakubja

In time, I established my own city—Kanyakubja, the “City of Virgins,” which you now know as modern-day Kannauj. I built it along the banks of sacred rivers, where sages could meditate and where my people could live in peace and prosperity. It was a place of harmony, with temples echoing the chants of Brahmins and the streets bustling with traders and artisans. I ruled there with justice and serenity. My kingdom prospered because I ruled not as a tyrant, but as a father to my people.

The Tale of My Hundred Daughters

The gods blessed me and my queen with a hundred daughters, each more beautiful and virtuous than the last. They were not ordinary children; their presence brought joy to all who beheld them. One day, while walking through the forest, they were approached by the wind god, Vayu, who desired them for wives. When they refused—politely but firmly—he cursed them to become hunchbacked and deformed. My heart wept for their suffering, but they never blamed me nor lost their grace. In time, I gave them all in marriage to the sage Brahmadatta, a man of great purity, who accepted them with their curse and freed them through his own spiritual merit. That was a moment of great healing, one that showed me the enduring strength of virtue and grace.

The Birth of My Son Gadhi

I had long desired a son to carry on my name and rule the kingdom. I performed penance, offered oblations, and prayed to Indra, the King of Heaven. Pleased with my devotion, he granted me a boon, and soon my queen bore me a son: Gadhi. I raised him with the same principles my father had passed to me—wisdom, courage, and above all, humility before the great mysteries of the universe. He grew into a ruler worthy of my throne, and my heart was filled with peace.

Watching the Future Unfold

I lived long enough to see my grandson born. Vishvamitra was radiant even as a child. There was a fire in him, a light that outshone kings and sages alike. Though I left this world before he rose to become a brahmarishi, I knew he would transcend the legacy I left behind. In him, the path of warrior and sage would merge into something divine. My blood flowed through kings, but my spirit would live on in a rishi whose name echoed across the ages.

My Legacy

I am remembered not for battles won or wealth gathered, but for the city I built, the family I raised, and the virtues I upheld. Kanyakubja became a cradle of learning and righteousness, and through my descendants—Gadhi and Vishvamitra—my name reached into the realms of myth and memory. I was Kushanabha, a king who cherished the path of dharma above all else. And in the quiet moments of history, I still walk the riverbanks of my city, smiling at the world that blossomed from my line.

The Great Turning of Life (Transition Hunters to Farmers) – Told by Kushanabha

Though I lived in an age of city and court, I was never blind to the long road that brought us there. Long before I raised my palace or heard the chants of Brahmins, there was a time when people wandered like the winds—chasing game, gathering fruits, and living in constant motion. But the world changed. The skies steadied, the rivers found rhythm, and the land, once wild and uncertain, began to offer itself to those who dared to stay. It was not sudden. It was not one choice, but many, woven across generations. The age of the hunter gave way to the farmer, and with it, the world was reborn.

Why They Chose to Stay

The shift began when the seasons grew gentler and more predictable. Rains came more regularly, rivers like the Indus and its tributaries flowed more faithfully, and the great plains remained lush and green for longer stretches. People noticed where the grasses grew tall and where the soil held water after the floods. They began to stay near those places. The land around Mehrgarh and the Bolan Pass was especially generous. Here, the earliest settlers saw that certain seeds—when dropped—grew again. They noticed that animals returned to graze in the same places each year. They began to wonder what might happen if they stopped chasing and started shaping. So they stayed.

The First Hands to Till

In those early days, farming was still as close to the earth as the soles of their feet. The tools were simple—sticks sharpened into digging tools, stones tied to wooden shafts for axes and plows, and grinding stones to break the harvested grain. Over time, they learned that some fields needed rest, and that planting different crops in a cycle preserved the strength of the soil. They watched the rivers and dug small channels to guide the water toward their fields—early irrigation, born not from script but from quiet observation. Their knowledge was practical and sacred at once, for they understood that to work with the earth was to live with it, not above it.

What They Grew and Raised

The first crops to feed their growing families were wheat and barley—strong grains that could withstand the sun and yield enough to store. They also cultivated lentils, pulses that gave strength to the body and life to the soil. These grains became the foundation of their meals and their future. Alongside their fields grazed the first companions of settled life—cattle with broad horns, sheep with thick wool, goats quick and clever. These animals gave not only meat and milk, but manure for the fields, hides for clothing, and companionship that tethered people to place. Where once they followed the herds, now the herds followed them.

How Life Was Transformed

With the land tamed and the fields producing, something new began to stir—security. Food became more predictable. Hunger, once a constant threat, now came only with misfortune. With full bellies came more children, and with more children, more hands to work the land. Villages grew, crafts blossomed. Some began shaping clay into pots, others wove reeds into baskets, or carved tools and ornaments from bone and stone. As people settled, their imaginations settled too—not into silence, but into creativity. They painted pottery, wove stories, and began to look at the stars not just with wonder, but with questions.

The Gift They Gave Us

Though I ruled from walls of brick and heard my name echoed in courts and temples, I never forgot that it was the farmer who first built civilization—not with stone, but with seed. Their quiet choices transformed the world. They made it possible for sages to chant, for kings to rule, for cities to rise. Their legacy is not only in the grain we eat or the animals we tend, but in the very shape of our daily life. To honor them is to honor the earth itself—for they were its first partners, and through them, we became who we are.

The Shaping of Earth (Development of Craftsmanship)– Told by Kushanabha

The story of humanity is not only told through battle and prayer, but also through clay—simple earth, molded by hand, touched by fire, and turned into something enduring. The development of pottery and craftsmanship marked a turning in our way of life, a new language not of words, but of form and function.

The First Bowls of Clay

In the early days of settlement, before the potter’s wheel or the painted vase, people learned to form bowls and jars with their hands. These early vessels were undecorated, lumpy, and thick—shaped by pinching and smoothing clay found near rivers and lakes. They dried them in the sun or placed them gently near fire pits. These humble pots held water, grain, and cooked food. Even in their roughness, they marked a turning point: the beginning of a relationship between humanity and material, permanence and purpose. These first steps into pottery were quiet, but they were a promise of refinement yet to come.

When the Wheel Was Born

In time, as villages grew and the rhythm of life became more stable, new knowledge emerged. Someone placed clay upon a spinning stone and discovered the wonder of uniformity. The potter’s wheel was born. With it came symmetry and grace. Vessels became smoother, thinner, and more beautiful. Patterns began to appear—not only for adornment, but to distinguish function or to honor ritual. Spiral designs, dotted lines, and geometric shapes were pressed or painted onto the surface. Clay, once just a tool of survival, became an expression of beauty, identity, and belief.

Holding More Than Grain

Pottery became more than a convenience. Large jars held the season’s grain, sealed tightly to guard against moisture and pests. Smaller bowls simmered lentils and barley near hearths. Some vessels, shaped with care and painted with rare pigments, were used in rituals to pour offerings of milk, ghee, or sacred water to the unseen gods. There were pots placed in graves, holding food for the journey beyond, or bearing beads and tokens of love. Pottery became an essential part of daily life, not only for survival, but for ceremony, memory, and meaning.

The Rise of the Artisan

As techniques grew, so too did those who dedicated their lives to craft. Kilns were built—first simple pit kilns, then enclosed ovens capable of greater heat. Pottery hardened more evenly, became more durable. Red and black slip gave vessels new color. Pigments from natural minerals added contrast and detail. Certain families, or even individuals, became known for their skill with clay or their fine stone tools. Craftsmanship began to emerge as a path of honor and specialization. These artisans were no longer just workers—they were the keepers of knowledge, shaping both objects and identity.

Why It Matters Even Now

I, Kushanabha, sit in a time of kings, but I look back with reverence to those who first placed their hands in clay and saw more than mud. The pot was the first home beyond the body. It held food, fire, water, memory. It linked the hearth to the field, the village to the spirit. In those simple vessels we find the fingerprints of a changing world, a people learning not just to live—but to endure, to create, and to connect. The path of craftsmanship is sacred. It reminds us that civilization is built not only by thought and law, but by the steady hand, the turning wheel, and the fire of patience.

The Flow of Goods and Ideas (Trade of Goods and Ideas) – Told by Kushanabha

In Mehrgarh, that ancient cradle near the Bolan Pass, where the first farmers laid their roots and where trade, like a slow and silent river, began to shape the course of civilization. Even in those early days, people did not live in isolation. They reached beyond their own fields and hills, seeking beauty, necessity, and meaning in what lay beyond the horizon.

The Earliest Threads of Trade

Though the people of Mehrgarh lived modestly in mud-brick homes, evidence shows they were not cut off from the wider world. Paths wound through mountain passes and across rivers, connecting them with the highlands of Iran, the plains of South Asia, and the lands reaching toward Central Asia. These were not formal empires or royal caravans, but networks of trust and barter, of shared needs and mutual curiosity. Traders and travelers carried more than objects—they carried stories, customs, and the spark of ideas. Through these early exchanges, even the quiet villages began to hum with the echo of distant lands.

What They Carried and Shared

The people of Mehrgarh traded in things both practical and precious. From the mines of Badakhshan in the north came lapis lazuli, deep blue like the night sky and prized for ornaments and offerings. Obsidian, sharp and glassy, traveled from volcanic lands to be shaped into blades. Marine shells, drawn from the distant coasts of the Arabian Sea, were polished and carved into beads, worn in life and buried with the dead. Turquoise, gleaming with green-blue light, found its way into their crafts. These items were not merely decoration—they carried power, prestige, and connection. When one wore a bead from a far-off land, one wore the story of that land as well.

The Influence of Exchange

Trade did more than bring objects. It brought change. As people encountered new tools and materials, they adopted and adapted them. Techniques in pottery, bead-making, and stone-carving evolved through shared knowledge. The decoration of vessels began to show distant motifs. Burial practices absorbed new customs, and the layout of villages began to reflect broader influences. This cultural blending helped shape early social norms, encouraging respect for specialized skills and perhaps planting the early seeds of status linked not just to family, but to craftsmanship and possession.

The Legacy of These Early Routes

I, Kushanabha, look back upon these ancient exchanges with reverence. It is easy to speak of kings and wars, but the silent footsteps of merchants and artisans often leave the deeper marks. The people of Mehrgarh did not hoard their knowledge. They reached outward. They understood, even without scripture, that humanity thrives when it shares, when it listens, when it learns from the other. These early trade routes were the first strings of a vast web—a web that would grow to bind empires, faiths, and peoples. The world we know was born not only in battle or temple, but in the humble act of offering one crafted bead to a stranger.

The Body’s Memory of the Past – Told by Kushanabha

In the high plains near Mehrgarh, where rivers once ran stronger and fields were green with promise, early people shaped not only the land but their bodies through toil, food, and healing. Their bones remain long after their voices have faded, and from those silent remains, we now hear the echoes of their health, their hunger, and their healing.

What Bones Have Told Us

From graves dated as early as 7000 BC, we now uncover truths etched in bone. The remains of those early villagers tell a story of hard lives lived with resilience. Their teeth, worn down by stone-gritted grain and fibrous plants, show us they relied heavily on grinding stones and unrefined flour. Many skulls bear the mark of cavities—signs of starchy diets and perhaps early sugars from gathered fruits. Yet others show surprisingly strong bones, evidence of physical labor and protein in their meals. Some remains, especially from later burials around 4500–3500 BC, show signs of arthritis, healed fractures, and even surgical intervention. These are not just bones—they are testaments to lives of struggle, survival, and healing.

The Food That Fed Them

The people of Mehrgarh lived from what the earth and their hands could provide. They raised barley and wheat, storing it in pits and grinding it daily for their meals. They gathered lentils and peas, and in the earlier periods, relied on wild berries, dates, and roots. Their cattle, sheep, and goats gave not only meat but also milk, forming a rich source of protein and fat. Milk was likely consumed fresh, but also fermented into curds or butter. Game animals—deer, wild boar, and fowl—were hunted on occasion, and fish may have come from the rivers in wetter years. Their diet was simple, but it was balanced by necessity, built around what could be grown, gathered, or preserved.

Healing Hands and Herbal Lore

Even without temples or scriptures, the people of Mehrgarh knew the art of healing. Around 3000 BC and later, we find evidence of trepanation—the careful drilling of holes into the skull, likely to relieve pressure from injury or perhaps to release spiritual afflictions. These skulls show signs of healing, meaning the patients often survived. That alone speaks of care, cleanliness, and after-treatment. They also turned to plants—turmeric, neem, ginger, and other herbs likely known to them even then, used in poultices, teas, or burned in smoke. They knew which leaves cooled a fever, which roots numbed a wound, and which stones soothed the stomach. Healing was passed from elder to child, memorized through practice, not written words.

The Strength of the Common Life

I do not look back on these early people with pity. Though they knew pain and sickness, they also knew care, kinship, and the strength that comes from shared burden. They lived not in cities, but in the rhythm of the earth. Their health was bound to the land—what it offered and what it withheld. Their bodies bore the marks of daily struggle, but also the quiet victories of adaptation and endurance. In them, I see the roots of our own knowledge, for the science of Ayurveda and the chants of Vedic healers were not born from the sky—they rose from the hands of those who first learned how to live, to eat, and to heal with the world around them.

Their Lessons in Our Time

Even now, in my halls where physicians mix herbs and chant verses for health, I remember that their knowledge began in firelight, beside grain pits and under starlit skies. From 7000 BC to the present age, the journey of health has never ceased. In Mehrgarh, it began—not in grand discoveries, but in small, persistent care. That, too, is a kind of wisdom. That, too, is a legacy.

The Rise of the Clever Hand – Told by Kushanabha

I am Kushanabha, king of Kanyakubja, a ruler in an age of order and ritual. Yet I find myself drawn to the time long before palaces and scrolls—when the people of the Indus frontier, in places like Mehrgarh, first began to shape the world with their hands. It was not kings who laid the foundation of civilization, but farmers and craftsmen whose quiet labor brought about the first age of innovation. Between 7000 BC and 3000 BC, these early settlers developed the tools and knowledge to transform raw land into a thriving life of permanence. Their legacy remains in the stone blades, water channels, and granaries still unearthed by those who listen to the soil.

The First Tools of Transformation

The earliest tools used by the people of Mehrgarh were fashioned from what lay close at hand. Flint and chert were chipped into sharp-edged blades, scrapers, and arrowheads. These tools were used not just for hunting but for preparing food, carving wood, and cutting reeds for shelters. By around 6000 BC, grinding stones appeared—large flat slabs upon which grains were crushed into flour with rounded handstones. Sickles, some made of stone and others from animal bone, were used to harvest wheat and barley. Bone tools, slender and strong, served as awls for leatherwork or needles for weaving. Each object, though humble in form, was a miracle of usefulness. They were the earliest proof that the human mind was not only to survive—but to shape the world around it.

Bringing Water to the Fields

Wherever crops are grown, water is king. The rivers near Mehrgarh—like the Bolan—offered natural life, but the rains were not always reliable. Around 5000 BC, the people began digging channels to guide water from the rivers to their fields. These early irrigation systems were simple, dug with hand tools and stone blades, but they marked a powerful shift. Water was no longer just a gift from the heavens—it became something to be managed, directed, and conserved. Small bunds and embankments helped retain floodwaters in fields, while furrows guided the flow through plots of barley and lentils. This control over water changed everything. It extended growing seasons, allowed more food to be produced, and gave the people confidence to settle deeper into the land.

Where the Harvest Was Kept

With the growth of crops came the need to store them. Around 5000 to 4000 BC, villagers in Mehrgarh began to build simple granaries—pits dug into the ground or structures made of mud-brick. Some were lined with stone or plaster to protect against pests and damp. These granaries were sealed with lids made of clay or packed earth. In them, wheat, barley, and lentils could be stored for seasons, ensuring food during dry months or lean years. Smaller containers, sealed with animal fat or beeswax, kept milk products, oils, or precious seeds safe. The storage of food was not only about survival—it allowed planning, trade, and the slow birth of wealth. A village that could store grain could feed its children, trade with neighbors, and withstand the turn of fate.

The Inheritance of Wisdom

As I ruled my city, I often looked at the implements of my farmers—their bronze-tipped plows, their stone rollers, their baskets of grain—and I remembered that every one of those things began in places like Mehrgarh, shaped by hands thousands of years before me. The people of that era may not have had temples or titles, but they had brilliance. They tamed water, sharpened stone, and preserved life in jars of clay. Their knowledge was passed not by scroll, but from palm to palm, generation by generation. From 7000 BC to 3000 BC, they taught the land to feed them—and in doing so, they taught us all what it means to build a future.

Their Tools in Our Time

We now live in the age of kings and scribes, but the spirit of those first innovators lives on. Every granary that feeds a village, every tool that cuts with purpose, every canal that brings water to seed—is their gift. I, Kushanabha, honor them not as subjects of a forgotten past, but as the first architects of our enduring world. Let us never forget that before the word was written, before the law was spoken, there was the tool, the field, and the hand that made them.

Wisdom of the Earth (Technological Advancements) – Told by Kushanabha

I am Gadhi, son of Kushanabha, ruler of Kanyakubja, and father of Vishvamitra, who rose to become a rishi among kings. Though my name is remembered for kingship and lineage, I have long honored not only the warriors and sages of our past, but those who quietly transformed the earth. The foundations of all civilization—ours included—rest upon the shoulders of those who once lived in simplicity but discovered the deepest truths in soil, stone, and water. From around 7000 BC to 3000 BC, in the land that would one day give birth to the Indus Valley Civilization, these early people reshaped the world with tools of flint, channels of clay, and jars filled with life.

The Tools that Tamed the Land

In the days long before mine, before cities were walled and hymns were chanted, people crafted tools from flint—sharp-edged stones struck by hand to create blades, scrapers, and burins. These were the first instruments of precision, used to shape wood, cut meat, and harvest grain. Around 6000 BC, the grinding stone came into common use. Grain was placed on flat slabs and crushed with hand-held stones, turning raw kernels into flour for bread or porridge. Sickles—often curved and fitted with flint teeth or made entirely of shaped bone—were used to cut barley and wheat at harvest. Bone itself, from cattle and deer, was shaped into awls, spatulas, and needles. These tools may seem simple to us now, but they represent a leap from living with nature to working in concert with it.

Guiding the Waters of Life

The people of Mehrgarh and similar early communities did not leave their crops to the whims of rain alone. As early as 5000 BC, they observed how water moved and began to shape it. Small channels were carved into the earth to bring water from nearby rivers and seasonal streams like the Bolan into their fields. These were not the grand canals of later civilizations, but they were enough. By guiding water to thirsty soil, they extended growing seasons and ensured that even in drier times, crops could grow. Bunds—raised earth boundaries—helped retain moisture, and in some areas, furrows were dug to direct flow and prevent runoff. This was the beginning of irrigation, born from keen observation and patient labor.

Keeping the Harvest for the Lean Times

Once food was grown and gathered, it had to be preserved. Around 4500 BC and onward, families and villages began to construct storage systems—granaries built from mud-brick or dug into the ground, sometimes plastered to prevent rot. These spaces held barley, wheat, and lentils, guarded against pests and weather. Some granaries were communal, placed at the heart of the village, while others were family-owned, dug beneath homes or courtyards. Smaller clay jars, often sealed with wax or resin, held oil, ghee, milk, or water. Storage was more than practicality—it was security. It meant one could survive the dry months, offer food in ritual, or trade when others lacked.

The Spirit Behind the Craft

When I look upon the fields of my kingdom, tilled by iron plows and sown with confidence, I remember those who first shaped stone to cut grain. When I see my people water their land, I think of those who dug the first channels by hand, guided only by the flow of instinct and stream. They did not rule kingdoms or compose hymns, yet they taught us how to live. Their gifts are not forgotten, for even the wisdom of a king depends upon the full granary and the skilled hand.

The Enduring Legacy

We live now in an age of complexity—of law, learning, and legend. But never forget that all this began in simplicity. From 7000 BC through 3000 BC, in the dust of early villages and among the green shoots of barley, humankind made its quiet revolution. They changed the world not by conquest, but by cultivation. I, Gadhi, carry that memory forward. For in every tool, every channel of water, and every grain stored for tomorrow, I see the enduring spark of those who first made civilization possible.

My name is Gadhi - My Lineage and Kingdom

I am Gadhi, a king descended from the line of the great sage Kusha, whose children founded noble clans across the sacred land of Bharata. My father was Kushanabha, a noble and just ruler. From him I inherited the throne of Kanyakubja, a prosperous kingdom nestled between rivers and forests. As king, I was trained in the dharma of ruling—upholding justice, protecting my people, and honoring the gods with sacrifices. My rule was not marked by conquest, but by stability, learning, and peace. I valued wisdom as much as strength, and I knew the importance of balance between earthly duty and spiritual insight.

A Prayer for a Child

As time passed, I longed for an heir who would be worthy of my throne and name. I turned to the divine. I performed penance and prayed to the gods for a son—one who would be strong, wise, and noble. In time, my prayers were answered. Through a boon from the god Indra himself, my wife and I were blessed with a son. He was born glowing like fire, with a presence too great for any mere warrior. We named him Vishvamitra, "friend of the world," for we knew he was destined for more than rulership alone.

Raising a Warrior, Not Knowing His Path

Vishvamitra grew under my watchful eyes. I trained him in the art of war, statecraft, and dharma. He was a brilliant student—courageous, strategic, and fair. I believed he would someday surpass even my rule, bringing Kanyakubja into an age of greatness. When he came of age, I gave him command of armies, and he won battles with valor and earned the loyalty of our allies. Yet, in all my hopes for him, I did not foresee the twist his life would take. Destiny had carved for him a path far beyond my own imagination.

The Day Everything Changed

He returned one day from the ashram of Sage Vashistha, not in triumph, but in turmoil. He told me how he had been humbled by a sage’s spiritual power—how Kamadhenu, the wish-fulfilling cow, had refused to serve a king and instead obeyed a brahmarishi. My son, once proud and commanding, was now restless. He no longer found glory in weapons or power. He desired something higher—the life of a sage. Though it saddened me to lose the heir to my throne, I knew that I could not hold him back. His spirit had outgrown my kingdom.

Watching from Afar

Years passed, and I heard tales of my son’s transformation. From forest to mountaintop, he endured trials no king could imagine. He faced gods, demons, and desires—and each time, he grew closer to the truth. He failed, yes, but always rose again. I, Gadhi, though once his king and father, became his student in silence. I learned that true power was not in ruling others, but in ruling oneself. I watched him earn the title of brahmarishi—not given lightly, and never claimed by birth.

My Final Thoughts

Though my name may be forgotten in the shadows of his greatness, I am proud. I am the father of Vishvamitra, and through him, my legacy became something eternal. In a time when the lines between warrior and sage were firmly drawn, he erased those boundaries and became a symbol of human potential. I gave the world a king. The world made him a rishi. And in that, I found my peace.

Echoes of Spirit in Ancient Earth (The Religion of the Mehrgarh) – Told by Gadhi

I am Gadhi, son of Kushanabha and father to Vishvamitra, who rose from king to sage and heard the sacred tones of the cosmos. But long before the hymns of the Rigveda were chanted beneath the open sky, there were people living in clay-walled homes near the rivers of Mehrgarh. From around 7000 BC to 3000 BC, they lived without written words, without temples of stone, but not without spirit. Their hands shaped more than tools—they shaped meaning. Though they left behind no scriptures, they left symbols and signs from which we, long after, can sense the rhythm of their beliefs.

The Art of Form and Meaning

In the settlements of Mehrgarh, archaeologists have unearthed small clay figurines, many of them shaped as women—broad-hipped, full-breasted, their forms simple but purposeful. These figures, dating from around 6000 to 4000 BC, speak not just of craft, but of reverence. Some say they were symbols of fertility, meant to honor the mystery of life and the sacred role of women as givers of birth and nourishment. Others believe they were offerings or protective icons, placed in homes to guard over hearth and harvest. Whatever their exact use, they show that these early people saw power in form, in the shaping of image as a vessel for hope, protection, or prayer.

Pottery, too, bore signs of more than function. From 5000 BC onward, vessels often displayed motifs—lines, spirals, dots, and waves—carefully arranged in patterns. While some may have been decorative, others likely held symbolic meaning. The spiral might mirror the cycle of life and death. The wave might echo the river’s life-giving flow. In their quiet repetition of pattern, these artisans whispered truths they perhaps could not yet speak.

Rituals of the Living and the Dead

Though no grand temples stood in Mehrgarh, clues to ritual remain. Within homes, some areas seem to have been set aside—platforms in corners, small hearth-like structures, or raised spaces with signs of repeated use. These may have been house altars, places where families offered grain, ghee, or ash to the unseen. Ritual, then, was woven into daily life, not separated from it. The sacred happened not only under the sky, but by the fire, beside the doorway, beneath the roof.

In death, they did not turn from care. From 6000 BC onward, bodies were laid in prepared graves, often with grave goods: necklaces of shell or stone beads, pots, tools, and in some cases, food. Some graves were beneath the floors of homes, others in small cemeteries just beyond the edge of the village. The presence of offerings tells us that they believed something lay beyond—perhaps a journey, perhaps a return, perhaps a lingering spirit among the family. The items left behind reflect love, respect, and a belief that the soul was not lost, only transformed.

A Culture Rooted in Earth and Spirit

These people did not speak of devas and asuras, nor did they chant verses passed down in meter and melody. But their actions speak to us all the same. In the care of the dead, in the careful shaping of a figurine, in the patterns etched upon a jar—they lived with meaning. Their religion was not separate from their living; it was in their hands, their homes, their fields. Perhaps they did not yet name the divine, but they felt it—in birth, in fire, in grain, in death.

The Foundation Beneath Our Faith

As I, Gadhi, watched my son leave behind kingship to walk the path of rishi, I saw in him the spirit of those ancient seekers. For what is faith but the search for truth and connection? The people of Mehrgarh began that journey in silence and clay. We have given it words and fire, but the roots remain. In the symbols they formed and the rituals they practiced between 7000 and 3000 BC, we glimpse the earliest stirrings of the sacred. Their world was not yet ours—but it gave rise to it. And for that, we must honor them—not as forgotten villagers, but as the first who looked beyond the visible and reached for the eternal.

Memory That Became a Civilization (Transition to the Indus) – Told by Gadhi

Among the ancient villages that once lay beneath the Bolan Pass, none holds such reverence in my mind as Mehrgarh. It was the quiet seed of something that would one day become vast and mighty: the Indus Valley Civilization. The spirit of Mehrgarh did not end when its walls crumbled; it transformed and flowed onward like a river, becoming the foundation of Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, and cities yet to rise.

The Continuity of Culture

When we study the cities of the later Indus Valley, from around 2600 to 1900 BC, we do not see something altogether new—we see echoes of Mehrgarh. The use of fired bricks, carefully aligned in straight rows, had its beginnings in those earlier homes of mud-brick. The layout of streets and drainage channels in cities like Harappa and Lothal show a sense of order that may have first taken root in the communal spaces of early villages. Pottery styles—painted with geometric designs, crafted by skilled hands—evolved directly from those in Mehrgarh. Even the ornaments made of shell, steatite, and lapis lazuli reflect an unbroken thread of beauty and identity. What began as handmade figurines and simple beads would become the refined seals and symbols of a civilization that traded across oceans and deserts.

From Hearth to City

How did this transformation occur? Some say it was the steady growth of knowledge—generation upon generation passing down the wisdom of irrigation, storage, and cooperation. As villages grew, they joined or competed with others. Trade expanded. Populations increased. Specialization became necessary. No longer could one man grow food, build his home, and shape his tools alone. Artisans arose. Leaders emerged. And so, the scattered hearths of Mehrgarh gave rise to streets, markets, and granaries. Around 3000 BC, some of these settlements began to show signs of central planning, suggesting that what was once communal had become organized. This was not a fall of the old ways, but their refinement.

Theories of Change and Renewal

Others say the change came not just through growth, but through challenge. Climate shifts around 2600 BC may have dried the rivers that once nourished Mehrgarh. The seasonal rhythms that supported their fields may have grown unreliable. Some families, seeing the danger, moved east and south, toward the Indus and its tributaries. There, they brought their traditions—brick-making, farming, trade—and wove them into new forms suited to larger, wetter plains. Mehrgarh may have faded, but it did not vanish. It dissolved into the cities it gave birth to. Its people became the builders of urban marvels, its spirit carried forward in every street, seal, and sculpture.

What We Owe Them

I, Gadhi, know well the value of heritage. My son Vishvamitra became a brahmarishi, but his strength grew from the roots I gave him. So too with the Indus Valley. It rose high because Mehrgarh held firm. The legacy of Mehrgarh is not merely its age, but its endurance—its quiet shaping of everything that came after. From 7000 BC to the flowering of Harappa in 2600 BC, it bore witness to humanity learning how to live with the land, with one another, and with the divine breath of creativity.

A Civilization Carried in the Hands of the Humble

It is tempting to honor only kings and scribes, but the true legacy lies in the hands of the farmers, potters, and builders who first dared to settle. Their memory is not carved into stone—yet it lives on, in the grid of a city, the curve of a pot, and the story that began in a village at the edge of the Bolan hills. The Indus did not rise from nothing. It rose from Mehrgarh, and Mehrgarh rose from those who listened closely to the earth. Let us never forget that.

Comments