14. Heroes and Villains of Colonial Life in the Americas: The Settlement of Russian Alaska

- Historical Conquest Team

- Sep 11, 2025

- 34 min read

Updated: Sep 12, 2025

Great Northern Expedition

My Name is Vitus Bering: Explorer of the North Pacific

I was born in 1681 in Denmark, far from the icy seas that would one day define my name. As a boy, I listened to tales of sailors who ventured into unknown waters, and I longed to do the same. My calling was not to stay home but to chart the edges of the world. That dream carried me to the Russian navy, where I began a life of exploration in service to a foreign empire.

First Expedition

In 1725, I was chosen to lead what became known as the First Kamchatka Expedition. The Russian Empire wanted to know if Asia and North America were connected, and I was tasked with solving the mystery. My men and I traveled across Siberia, a journey almost as hard as the sea itself. From Kamchatka we sailed northward and eastward, reaching the strait that now bears my name. Though we did not sight America clearly, we proved Asia and America were divided by water.

The Great Northern Expedition

A few years later, I was asked again to command another mission: the Second Kamchatka Expedition. It was massive, one of the greatest explorations of its time. My orders were to map Russia’s far eastern lands, explore the Arctic, and search for new routes across the Pacific. In 1741, I set sail from Kamchatka and finally sighted the rugged coast of Alaska. We anchored near Mount Saint Elias, and my crew stepped on American soil for the first time under the Russian flag.

Struggles and Suffering

The return journey was crueler than any storm. Disease spread among my men, and supplies ran thin. Our ship wrecked on a desolate island in the Commander chain. There, weak with scurvy, I could no longer lead. I died in December of 1741, never knowing that history would remember my name for the waters I crossed.

Legacy

Though I did not live to see it, my voyages opened the door to Russian Alaska. Traders, settlers, and priests followed where we first landed. The Bering Sea, Bering Strait, and Bering Island were named in my honor, reminders of the paths I charted. My life was a tale of hardship and discovery, but I am proud to have pushed the boundaries of the known world.

Russia’s Ambitions in Siberia and the Pacific (Early 1700s) – Told by Vitus Bering

When I first entered Russian service, the empire was already stretching its reach across the endless forests and rivers of Siberia. Hunters, traders, and soldiers pushed eastward, driven by the wealth of sable and other furs. Each step brought new forts and settlements, but it also revealed how vast and difficult the land truly was. Siberia was not just an expansion of territory; it was a test of Russian endurance.

The Lure of the Pacific

By the early 1700s, Russia looked beyond the frozen rivers to the great ocean that lay ahead. The Pacific was a frontier of mystery. Did Asia and America connect? Could there be new trade routes or undiscovered lands? The empire wanted answers. Peter the Great himself urged his advisors and captains to explore these questions, for he knew that knowledge of the seas would give Russia both power and wealth.

Fur and Fortune

The promise of sea otter pelts was enough to drive men into dangerous waters. These pelts were more valuable than silver in the markets of China. To reach them, Russians had to cross stormy seas and rely on fragile ships. Yet the rewards were too tempting to ignore. For the empire, Siberia was no longer just a frozen wilderness but a gateway to riches that lay across the ocean.

The Birth of Expeditions

It was in this spirit that Peter the Great called for expeditions to explore the easternmost edge of his realm. He sought to map the coasts, discover new lands, and prove Russia’s strength as a seafaring nation. I was chosen to lead these missions not because of wealth or noble birth, but because of experience and determination. My voyages became the answer to Russia’s growing ambitions in the Pacific, ambitions that would carry the empire all the way to Alaska.

First Kamchatka Expedition and Mapping the Eastern Frontiers – Told by Bering

In the year 1725, as Peter the Great’s reign drew to its close, he commanded that an expedition be sent to the farthest edge of Russia. His dream was to know whether Asia and America were joined as one land or separated by water. It was a question that could change trade, navigation, and Russia’s power in the Pacific. I, Vitus Bering, was chosen to lead this mission, and I accepted the task with solemn duty.

The Journey Across Siberia

To reach Kamchatka, we first had to cross the endless stretch of Siberia. Rivers had to be forded, forests cut through, and mountains climbed. Supplies were hauled by sleds and barges, and men endured bitter cold and hunger. Months of toil brought us at last to the port of Okhotsk, where we built ships with our own hands. From there we sailed to the Kamchatka Peninsula, the true launching point of the expedition.

Into the Unknown

From Kamchatka in 1728, I led my men northward along the coast in the ship Saint Gabriel. The waters were icy and rough, and fog often hid the shore from sight. We followed the coast as far as we could, pushing through the strait that later bore my name. Yet we did not see the American shore, only open sea stretching beyond the horizon. It was proof that Asia and America were divided, though no eye from our crew had yet glimpsed the distant continent.

The Work of Mapping

We made careful records of the lands and waters we passed. My officers and I charted the coasts, noted the islands, and recorded the wildlife and peoples we encountered. These maps, though incomplete, gave Russia its first true picture of the eastern frontier. They became the foundation for later expeditions and the empire’s push toward the Pacific.

The Meaning of the Expedition

Though some judged the expedition too cautious, I knew our discoveries were vital. We had not failed; we had opened a door. By proving that a strait divided Asia from the New World, we gave Russia both opportunity and challenge. The First Kamchatka Expedition was not the end of discovery but the beginning, and it set the course for my life and for Russia’s future in the Pacific.

Second Kamchatka Expedition and the Voyage Toward Alaska – Told by Bering

After the First Kamchatka Expedition, Russia’s leaders hungered for more knowledge. The coasts of Siberia were still unknown in many places, and the mystery of lands beyond the Pacific had not been solved. In the 1730s, I was once again chosen to lead a mission, this time far larger and more ambitious than the first. It came to be called the Great Northern Expedition, and it was one of the greatest explorations of its time.

Crossing Siberia Once More

To begin the work, hundreds of men, scientists, craftsmen, and soldiers marched with me across Siberia. We carried tools, supplies, and even prefabricated parts for ships. The journey was grueling, taking years to reach Okhotsk and Kamchatka. Many died of exhaustion, and yet the vision of discovery drove us onward. At last, in the shipyards we built, two vessels rose: the St. Peter, which I commanded, and the St. Paul under Captain Chirikov.

Sailing into the Pacific

In June of 1741, we set out from Kamchatka. Storms separated our ships, and I continued eastward with my crew aboard the St. Peter. After weeks of hardship, we finally saw towering mountains rising from the sea. It was the coast of Alaska, near what is now Mount Saint Elias. For the first time, Russia laid eyes on the American continent, and I knew we had fulfilled part of Peter the Great’s vision.

Exploration and Hardship

We anchored on the shores and gathered fresh water and supplies. We traded with the native peoples and studied the land. But the weather turned against us, and disease spread among my men. On the return voyage, scurvy claimed many lives, and storms battered the St. Peter. Weak and weary, we wrecked on an uninhabited island in the Commander chain. There we tried to survive with what little we had.

The End of My Voyage

I did not live to return to Kamchatka. In December of 1741, scurvy and weakness overcame me on that lonely island. My men buried me in the sand, far from the homeland I served. Yet the maps we made and the lands we reached proved Russia’s place in the Pacific. The Second Kamchatka Expedition carried Russian eyes to Alaska, and though it cost me my life, it opened the way for colonists and traders who followed in our path.

Discovery of the Aleutian Islands and First Encounters with Alaska – Told by Bering

When we left Kamchatka during the Second Kamchatka Expedition, our purpose was to push farther east than any Russian ship had gone before. The Pacific stretched wide and uncertain before us, but I was determined to find the lands rumored beyond the horizon. With the St. Peter under my command, we pressed into waters no European had yet charted, guided by faith in our mission and the strength of my crew.

Islands Rising from the Sea

It was during this voyage that we came upon a scattered chain of islands stretching like stepping stones across the ocean. These were the Aleutian Islands, rocky and windswept, yet rich with life. We noted the seals, sea otters, and whales that filled the waters, their presence signaling both danger and promise. For the Russian Empire, these islands marked the beginning of a bridge between Asia and America, a frontier that would soon become vital for the fur trade.

First Glimpses of Alaska

As we sailed beyond the Aleutians, a greater sight revealed itself—the massive, snow-covered peaks of the Alaskan mainland. Near Mount Saint Elias, we anchored to gather water and supplies. My men stepped ashore, making contact with the land that lay across the ocean from Russia. For the first time, we proved that the empire could reach the shores of North America.

Encounters with Native Peoples

On these shores, we met native peoples whose lives were tied to the sea and its creatures. Though our meetings were brief, they revealed a world rich in culture and survival skills that had long endured in these harsh lands. To my men, their presence was a reminder that these were not empty coasts waiting for discovery, but homelands that had been lived in for countless generations.

The Meaning of Discovery

Our sighting of the Aleutian Islands and the first steps onto Alaska did more than expand a map. It laid the foundation for Russia’s future in America, opening the way for traders, settlers, and missionaries. Though storms, illness, and hardship soon took their toll on us, I knew then that we had accomplished something of lasting importance. We had carried Russia across the Pacific and touched the edge of a new continent.

Hardships of Exploration and My Death on Bering Island – Told by Vitus Bering

After sighting the Alaskan coast and discovering the Aleutian Islands, my men and I turned our ship, the St. Peter, back toward Kamchatka. We carried news of success, but our bodies and supplies were failing. The Pacific was unforgiving, and every mile became a battle against the sea, the cold, and our own weakness.

The Spread of Scurvy

Scurvy began to strike my crew with merciless speed. Gums bled, teeth fell out, and men grew too weak to stand. We had little fresh food to fight the sickness, and every day I watched more sailors collapse. As commander, I bore the weight of their suffering, yet I too felt my own strength draining away.

Shipwreck and Struggle

Storms pushed us off course, and by November of 1741, the St. Peter was wrecked on an uninhabited island in the Commander chain. There we built makeshift shelters from driftwood and pieces of the broken ship. The men hunted sea otters and seals, and though they worked with determination, the island felt like a prison of wind and snow.

My Final Days

I was too weak to join them. Confined to a shallow pit lined with animal skins for warmth, I lay as scurvy consumed me. My body was frail, my vision dim, but I still thought of the mission and the empire I had served. On December 19, 1741, I breathed my last on that desolate shore, never to return home to Russia.

Legacy Beyond Death

Though I died on the island that now bears my name, my men endured. They survived the winter, built a new vessel, and carried our discoveries back to Kamchatka. Through them, Russia learned of Alaska, the Aleutians, and the Pacific frontier. My end was harsh, but it was not in vain. I gave my life to exploration, and in death, I left behind a path for others to follow.

Russian Columbus of Alaska

My Name is Grigory Shelikhov: Founder of Russian Colonies in Alaska

I was born in 1747 in Russia, the son of a merchant. From an early age, I understood the power of trade and the wealth that could be gained from distant lands. Siberia’s rivers carried furs to market, but I dreamed of something greater. I wanted to expand Russia’s reach across the Pacific and claim new territories for both profit and empire.

The Call of the Sea

I became a merchant sailor, learning the dangers of storm and ice. Yet those hardships only hardened me for the task ahead. By the 1780s, sea otter pelts had become the most valuable commodity in the Pacific, and I knew Alaska held vast riches. I prepared an expedition not just for hunting but for settlement, determined to plant Russia’s presence firmly on American soil.

Voyage to Kodiak

In 1783, I set sail with several ships toward the distant islands of Alaska. After years of navigating treacherous waters, I arrived in 1784 at Kodiak Island. There, I established the first permanent Russian settlement. It was not an easy beginning. Conflict with the native Alutiiq people turned violent, and blood was shed in the name of conquest. These acts weighed on me, yet I believed they secured Russia’s hold on the land.

Building a Colony

I built schools, churches, and trading posts on Kodiak. My settlements became centers of Russian culture and faith in the New World. I brought priests to baptize the natives, and I trained workers to manage the fur trade. To strengthen my efforts, I founded the Shelikhov-Golikov Company, which later merged into the great Russian-American Company. Through it, I tied the fur trade to the empire itself.

Final Years and Legacy

Though I returned to Russia, my thoughts remained in Alaska. I wrote to Catherine the Great, urging her to support colonization and protect these distant holdings. My life ended in 1795, before I could see how far the colonies would grow. Yet my work lived on through my family and my company. They carried forward the vision I began, a vision that laid the foundation for Russia’s rule in America. My name is remembered as the man who brought Russia across the Pacific and built the first lasting settlements in Alaska.

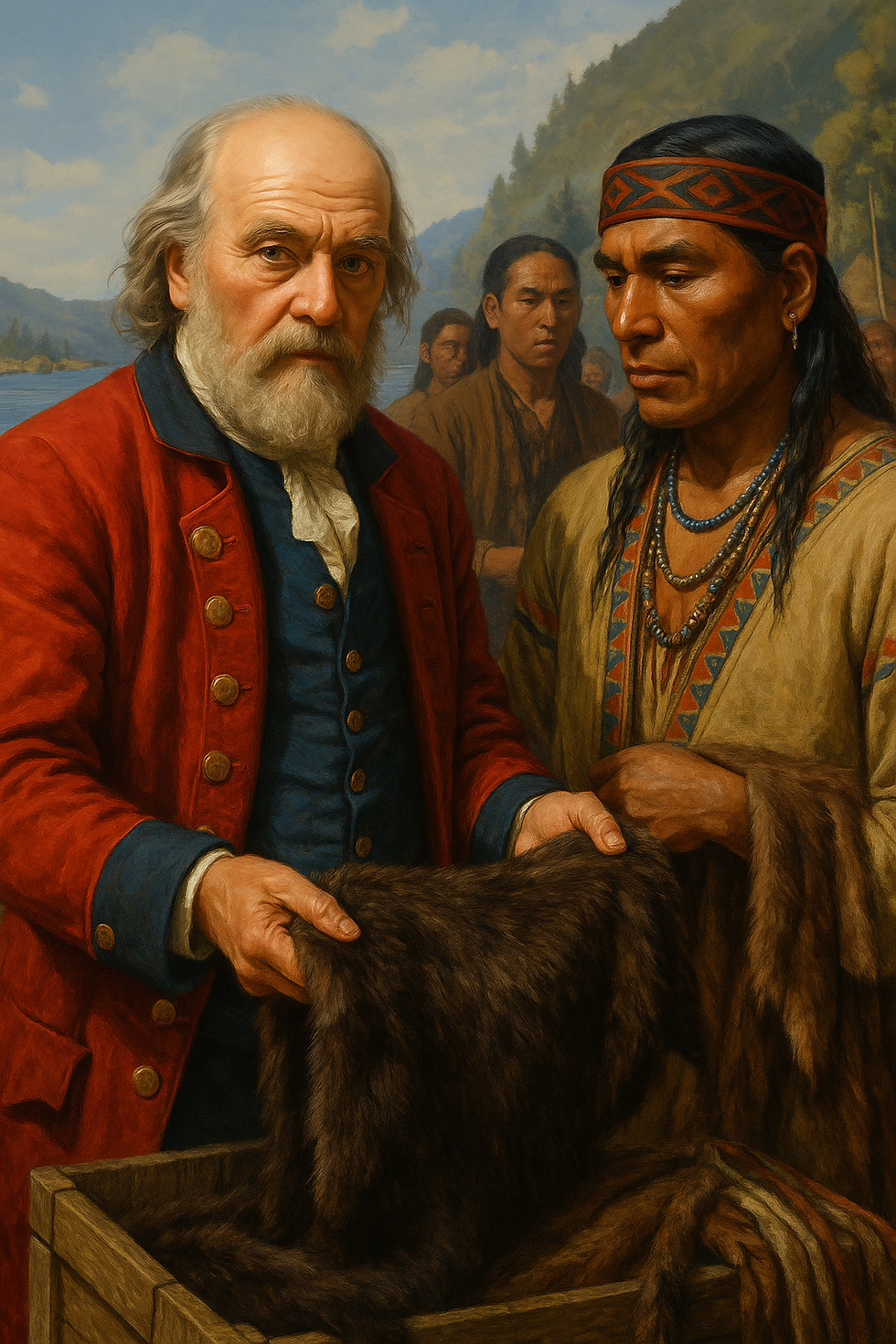

Rise of the Russian Fur Trade and Demand for Sea Otter Pelts – Told by Shelikhov

Long before I set sail for Alaska, Russia’s fortune in the east was built on the fur trade. Hunters and trappers crossed Siberia, trading with native peoples and sending back sable, fox, and ermine. These furs fetched high prices in Moscow and St. Petersburg, but the market was never satisfied. Merchants like myself saw opportunity, for every step eastward brought new lands and new sources of wealth.

The Discovery of Sea Otters

It was the sea otter that changed everything. In the cold waters of the North Pacific, this animal’s pelt was unlike any other. Its fur was the densest in the world, soft and shimmering, prized above silver and gold in the markets of China. Once the first pelts reached the Qing Empire, demand grew insatiable. Suddenly, the wilderness of the Aleutian Islands and Alaska became a treasure chest waiting to be opened.

Merchants and Expeditions

Russian merchants quickly organized expeditions to harvest sea otters. Crews were sent in small ships across treacherous waters, braving storms, ice, and long months away from home. Hunters forced native Aleuts and Alutiiq to join them, using their knowledge of the land and sea to capture more animals. The profits were immense, but the risks were just as high. Many ships never returned, lost to weather or conflict.

The Drive for Colonization

The demand for pelts did more than enrich merchants; it pushed Russia to establish settlements in Alaska. Trade alone was not enough—we needed permanent posts, supplies, and control of the land to keep rivals away. It was this hunger for sea otter furs that inspired my own voyages and the colonies I later founded on Kodiak Island. Without that trade, Russia might never have crossed the Pacific to America.

The Cost of Wealth

Yet I must also admit the cost. Entire populations of sea otters were hunted nearly to extinction, and native peoples suffered greatly under the weight of forced labor and violence. The wealth of the fur trade came at a terrible price for the people and the animals of Alaska. Still, in my time, the demand was unstoppable, and it shaped the empire’s expansion across the ocean.

Shelikhov’s Voyage to Kodiak Island (1784) & First Settlements – Told by Shelikhov

By the early 1780s, the wealth of the sea otter trade had drawn many daring men into the North Pacific, but I wanted more than fleeting profit. I sought to establish a true Russian presence in America. In 1783, I outfitted an expedition of several ships with men, supplies, and the determination to plant the first lasting colony across the ocean. Our goal was Kodiak Island, a place rich in resources and strategically placed along the Aleutian chain.

Arrival at Kodiak

After a long and treacherous voyage, we reached Kodiak Island in 1784. Its coast was rugged, with dense forests and rocky shores, a land both promising and harsh. There we anchored, bringing ashore tools, weapons, and food, ready to carve out a settlement. For the Russian Empire, this was more than a camp—it was a foothold in the New World.

Conflict with the Alutiiq People

Yet our arrival was not welcomed by all. The Alutiiq people already lived and thrived on the island, and they resisted our intrusion. Tensions turned violent when we sought to force their labor for the fur trade. In a brutal conflict at Refuge Rock, many Alutiiq were killed, and their families taken captive. It was a moment of conquest that secured our settlement but left a shadow of blood upon its foundation.

Building the Settlement

After the conflict, I set about building what became the first permanent Russian post in Alaska. We raised barracks for the men, storehouses for supplies, and a chapel for worship. Craftsmen worked to repair our ships and fashion tools, while hunters set out daily to bring back food and furs. The settlement grew into a small but firm colony, a center of Russian power in this distant land.

The Legacy of Kodiak

Our settlement at Kodiak was the beginning of Russian America. From there, future posts would spread, and trade would flourish under the Russian-American Company. Though born of hardship and conflict, Kodiak became the symbol of Russia’s determination to hold Alaska. For me, it was the achievement of a dream: to carry Russia across the Pacific and plant its flag in a new world.

Relations with the Alutiiq People and the Violence of Conquest – Told by Shelikhov

When we landed on Kodiak Island in 1784, we entered a land already inhabited by the Alutiiq people. They were skilled hunters, fishermen, and craftsmen, living in balance with the sea and forests. At first, our interactions were uneasy but restrained. We traded with them for food and knowledge of the land, yet from the beginning there was mistrust. They saw us not as guests but as intruders, and in truth, we came not to share their home but to claim it.

Tensions Rising

The demand for sea otter pelts pressed heavily on my men and me. The Alutiiq resisted when we tried to force them into labor for the fur trade, and small skirmishes broke out. Each side watched the other with suspicion, and I knew the fragile peace could not last. To establish a Russian settlement, I felt compelled to break their resistance, though I understood it would bring bloodshed.

The Tragedy at Refuge Rock

The conflict reached its height at a place called Refuge Rock, where many Alutiiq families had taken shelter. My forces attacked, armed with muskets and cannon against their bows and spears. The outcome was swift and brutal. Many Alutiiq were killed, others captured, and their community shattered. It was a day of conquest that opened the way for our settlement, but it was also a day marked by sorrow and loss.

Captives and Control

After the battle, we forced surviving Alutiiq into service, compelling them to hunt and labor for the Russian trade. Their families were divided, their freedom stripped away. This brought us short-term control and wealth, but it left deep scars between our people. Fear and resentment lingered, even as we baptized some into the Orthodox faith and sought to fold them into the colony’s life.

The Weight of Conquest

I often told myself that such violence was necessary for the empire’s expansion and for securing Alaska for Russia. Yet I cannot deny the harshness of our methods and the suffering they caused. The Alutiiq paid dearly for our ambitions, their lives torn apart so that we could plant a colony. History remembers Kodiak as the beginning of Russian America, but for the Alutiiq, it was also the beginning of dispossession and sorrow.

Establishing Permanent Russian Posts in Alaska – Told by Grigory Shelikhov

When I first reached Kodiak Island, I knew that simple camps would not be enough to hold Russia’s place in America. Temporary shelters could not withstand the winters, nor could they guard against native resistance or foreign rivals. To make our presence lasting, we needed permanent posts—fortified settlements that could support trade, provide security, and anchor the empire in this new world.

Building Kodiak Settlement

On Kodiak, I ordered the construction of barracks, storehouses, and workshops. We built from timber and stone, raising structures that would endure the storms. A chapel soon followed, for faith was as important to the colony as food and weapons. From this base, we could manage hunting expeditions, repair ships, and gather furs for trade. Kodiak became the first heart of Russian America, a place where settlers, traders, and even families could begin a new life.

Expansion Beyond Kodiak

Once our foothold on Kodiak was secure, I looked to spread our reach farther along the coast. Small outposts were established on surrounding islands, each meant to watch over hunting grounds and secure more pelts. These posts were manned by a handful of Russians, often with Aleut or Alutiiq laborers forced into service. Though small, they created a network that linked the colony together and gave Russia greater control of the region.

Support from the Homeland

To strengthen these settlements, I appealed to the crown and to merchants back in Russia. I needed supplies, reinforcements, and imperial recognition. By forming the Shelikhov-Golikov Company, I tied my efforts to the empire itself. With its backing, our posts were no longer just the ventures of a single merchant but part of Russia’s larger vision for the Pacific.

A Foundation for the Future

These permanent posts became the skeleton of Russian Alaska. They allowed trade to thrive, priests to spread the Orthodox faith, and the empire to claim a foothold in a distant land. Though life was harsh and conflict never far away, the settlements endured. They were the beginning of a colony that would last for generations, proof that Russia’s banner could be planted firmly across the ocean.

Founding the Shelikhov-Golikov Company (Later the Russian-American Company) – Told by Grigory Shelikhov

When I returned from Kodiak to Russia, I knew that the colonies could not survive on scattered merchants and small expeditions alone. The fur trade was too vast, the risks too high, and the competition too fierce. What Russia needed was structure—a company strong enough to organize the trade, supply the colonies, and defend our claims against rivals.

Partnership with Golikov

To achieve this, I partnered with Ivan Golikov, a wealthy merchant of Moscow. Together we pooled our resources, ships, and connections, forming what became known as the Shelikhov-Golikov Company. This was not a mere trading venture; it was the foundation of Russia’s colonial enterprise in America. With Golikov’s wealth and my experience in Alaska, we presented ourselves as leaders of a new era of expansion.

Imperial Support

I petitioned Catherine the Great and her officials, urging them to recognize the importance of Alaska. I argued that our posts there not only brought wealth through furs but also gave Russia a strategic foothold in the Pacific. Though I did not live to see it fully realized, these appeals paved the way for imperial charters that gave our company exclusive rights to trade and govern in Alaska.

The Growth of Power

With the company’s backing, our settlements grew stronger. We supplied Kodiak and other posts, sent more expeditions into the Aleutians, and expanded our influence among the native peoples. The company gave order to the chaos of early colonization, turning scattered outposts into a system of trade and governance. It was a step toward making Alaska not just a land of hunters but a province of empire.

From Shelikhov-Golikov to the Russian-American Company

After my death in 1795, my company merged with others to become the Russian-American Company, formally chartered in 1799. This new organization carried forward my vision, holding monopoly rights and governing Alaska on behalf of the crown. Though I did not live to see its rise, I take pride in knowing that it was born from my efforts. The Shelikhov-Golikov Company was the seed, and from it grew the empire’s strongest instrument in America.

Russian-American Company

My Name is Alexander Baranov: Governor of Russian America

I was born in 1747 in Kargopol, a small town in northern Russia. My father was a merchant of modest means, and I learned early the value of hard work and determination. I never imagined I would one day rule over lands across the ocean, but I had a restless spirit and a talent for trade that pushed me toward new horizons.

Journey to Siberia

As a young man, I moved eastward into Siberia, where opportunities for trade were greater and risks even higher. I built a small fortune in commerce, but debts and setbacks haunted me. When Grigory Shelikhov offered me a chance to manage his company’s interests in Alaska, I seized it. It was not just a job but a chance to make my mark in history.

Life in Alaska

I arrived in Kodiak in 1790, a land wild and unforgiving. I became manager of Shelikhov’s colony and later the chief of all Russian America. It was a heavy burden, but I accepted it with resolve. I built schools, churches, and trading posts, and I worked to establish order among settlers and natives alike. My methods were harsh at times, but survival in this land demanded strength.

Conflicts and Challenges

The fur trade drove our existence, but it also caused strife. Native peoples resisted Russian domination, and in 1802 the Tlingit attacked our settlement in Sitka. Two years later, I led a counterattack in the Battle of Sitka, reclaiming the territory and building New Archangel, which became the capital of Russian America. Beyond warfare, I struggled with hunger, isolation, and the constant threat of foreign rivals—Spain, Britain, and the young United States.

Legacy of Leadership

For nearly three decades, I governed Russian America as its first chief manager of the Russian-American Company. I became known as the “Lord of Alaska,” though I often longed only for peace and security for my people. In 1818, I finally left the colony, weary and aged. I died a year later on my voyage home. Yet my name endures in the towns, islands, and stories of Alaska. My life was one of hardship and conquest, but I will always be remembered as the man who built the foundations of Russian America.

Consolidating Russian Power in Kodiak and Sitka – Told by Alexander Baranov

When I first set foot on Kodiak Island in 1790, I inherited both the promise and the burden left by Grigory Shelikhov. The settlement was fragile, plagued by hunger, poor supplies, and tensions with the native Alutiiq people. My task was not simply to manage a colony but to transform it into the firm foundation of Russian America. I worked tirelessly to organize labor, enforce discipline, and establish schools and churches so that Kodiak would become more than a trading post—it would be a community.

Strengthening Trade and Control

The fur trade was the lifeblood of our existence, and I dedicated myself to making it efficient and profitable. I oversaw hunting expeditions across the Aleutians, often relying on native labor, though this brought resentment and hardship. I secured warehouses, built ships, and ensured that furs flowed back to Russia. Through strict management, Kodiak became the center of our operations, a base from which Russian influence spread across the Pacific frontier.

Turning to Sitka

Yet Kodiak was not enough. To truly secure Russian power, we needed a stronghold farther south, where the Tlingit controlled rich hunting grounds. In 1799, I led settlers and workers to Sitka, where we built a fort and claimed the land. But the Tlingit resisted fiercely, and in 1802 they rose against us, destroying our post and killing many of our people. It was one of the darkest moments of my career, but I would not surrender our claim.

The Battle for Sitka

Two years later, in 1804, I returned with reinforcements and cannon. At the Battle of Sitka, we clashed with the Tlingit in a brutal struggle for control. Though they fought bravely, we forced them to retreat. Afterward, I built New Archangel, a fortified settlement that became the capital of Russian America. From its palisades, Russia projected its power across Alaska, and Sitka stood as both a symbol of conquest and a seat of governance.

The Foundations of Russian America

By consolidating our hold on Kodiak and Sitka, I secured the pillars of Russian rule in America. These settlements were not just outposts but the heart of an empire’s reach across the Pacific. They provided trade, defense, and administration for decades to come. Though the work demanded hardship and harsh measures, I take pride in knowing that I laid the foundation of Russia’s dominion in Alaska.

Building Fort Alexander and Fort Ross – Told by Alexander Baranov

Once Kodiak was established as the center of Russian America, I turned my eyes to other lands that could strengthen our position. The fur trade demanded constant expansion, and to secure new hunting grounds and protect our people, forts had to be built. Each stronghold was not only a base for trade but also a symbol of Russia’s presence in lands far from home.

Fort Alexander in Alaska

On the shores near present-day Sitka, I ordered the construction of Fort Alexander. It was built to guard our interests among the Tlingit, whose resistance threatened our settlers and hunters. The fort was modest in size, made of timber with barracks and storehouses, but it gave us a place to stand firm in a contested land. From Fort Alexander, we launched hunting expeditions and extended Russian authority deeper into Alaska, though it remained a place of tension and conflict.

Looking Southward

As years passed, I realized that Alaska alone could not sustain our colonies. Supplies from Siberia were scarce and unreliable, and the settlements often starved. I looked to the warmer lands of California, under Spain’s weak hold, as a place where we might grow crops, raise cattle, and sustain our northern colonies. It was a bold vision, one that stretched Russia’s reach far beyond the icy coasts of Alaska.

Founding Fort Ross

In 1812, under my direction, Ivan Kuskov established Fort Ross along the coast of California, north of San Francisco Bay. Built of redwood and surrounded by farmland, it became our southernmost settlement. There we raised wheat, vegetables, and livestock, supplying food not only for Fort Ross but also for Kodiak and Sitka. It was a rare place where Russia’s settlers could live in a gentler climate, and it marked the farthest expansion of our empire in America.

The Legacy of the Forts

Fort Alexander anchored our rule in Alaska, while Fort Ross opened a window into California. Both were vital to the survival of Russian America, even if they stood in lands where our presence was never fully secure. Though Fort Ross would later be abandoned, it showed how far we had carried Russia’s ambitions. For me, these forts represented the reach of my efforts, stretching from the cold seas of Alaska to the fertile hills of California.

Managing Relations with Native Groups: Aleut, Tlingit, and Others – Told by Alexander Baranov

When I first arrived in Alaska, the Aleut people were already deeply entangled in the Russian fur trade. My predecessors had forced them into labor, often harshly, compelling them to hunt sea otters for the empire. I tried to bring more order to these relations, setting rules for labor and offering goods in exchange, but survival of the colony often outweighed fairness. The Aleut became both allies and subjects, their knowledge of the sea and hunting skills indispensable to our success.

The Alutiiq and Kodiak Settlement

On Kodiak Island, we depended on the Alutiiq people for food, guidance, and labor. Yet these ties were strained by the memory of violence from Shelikhov’s conquest. I worked to stabilize relations by building schools and encouraging baptism into the Orthodox faith, hoping to soften resentment. Still, many Alutiiq saw our presence as domination, and peace was fragile.

The Fierce Resistance of the Tlingit

Of all the native groups, the Tlingit were the most determined to resist Russian expansion. They were proud, skilled warriors who defended their land with courage and unity. At Sitka, our presence led to open conflict. In 1802 they destroyed our fort, killing many settlers and hunters. I could not let such a defeat stand, and two years later I returned with cannon and soldiers. The Battle of Sitka in 1804 was hard fought, and though we prevailed, the Tlingit never fully submitted. Their resistance remained a constant reminder that our power was contested.

Other Peoples of Alaska

Beyond the Aleut, Alutiiq, and Tlingit, we encountered many smaller groups across Alaska’s vast lands. Some traded with us willingly, exchanging furs for tools, beads, and firearms. Others avoided contact altogether. Each group had its own traditions, languages, and ways of life, and managing relations with them required caution, diplomacy, and sometimes force.

The Balance of Power

For me, managing these relations was the most delicate task of governance. Without the cooperation of native peoples, Russian America could not survive. Yet our hunger for furs and land often pushed us into conflict. I sought to balance strength with negotiation, faith with trade, but the weight of empire always pressed heavily upon them. The history of my time in Alaska cannot be told without the voices of the Aleut, Tlingit, Alutiiq, and many others, for they shaped the destiny of Russian America as much as I did.

Economic Exploitation: Fur, Trade, and Supply Challenges – Told by Baranov

The heart of our economy in Russian America was the fur of the sea otter. Its pelts were finer than any other, so dense and soft that in China they were valued above silver. To feed the empire’s hunger, we sent hunters across the Aleutian chain and down the Alaskan coast. Native peoples, especially the Aleut, were compelled to do much of this work, often at great cost to their lives and freedom. The wealth that flowed from their efforts built the foundation of Russian America.

Building Trade Networks

Once collected, the furs had to reach markets across the world. We shipped them first to Siberia, then overland to China, where they were traded for silk, porcelain, and tea. Later, ships carried them directly across the Pacific. Our network stretched from Kodiak and Sitka to Okhotsk, and from there to the heart of Russia and beyond. Each link in this chain was fragile, threatened by storms, rivals, and the sheer distance of travel. Yet when it held, the profits were immense.

Reliance on Native Labor

To maintain these networks, we relied heavily on the skills of Alaska’s native peoples. The Aleut and Alutiiq paddled their skin boats with unmatched skill, hunting sea otters in dangerous waters. But this reliance also meant coercion, and many were forced into service against their will. Families were divided, villages disrupted, and resentment grew. Still, without their knowledge and labor, our trade could not have survived.

Supply Struggles in the Colonies

Even with wealth in furs, our colonies often faced hunger. Supplies from Siberia were irregular, delayed by distance, weather, and poor planning. Ships wrecked, caravans were lost, and settlers starved in the harsh winters. To survive, we bartered with native peoples for fish and game, and later turned to California to grow crops and raise cattle. Fort Ross became vital in this effort, though even it could not solve every shortage.

The Burden of Exploitation

The fur trade brought riches to merchants and to the empire, but in Alaska itself it brought hardship. Native peoples bore the heaviest burden, and the sea otter was hunted nearly to extinction. Even settlers struggled, living at the mercy of supply routes and trade winds. I oversaw these efforts with determination, knowing they were necessary to keep Russian America alive. Yet I also knew that this system was fragile, built on exploitation and the uncertain bounty of the land and sea.

Conflicts with the Tlingit and the Battle of Sitka (1804) – Told by Baranov

Among all the native peoples of Alaska, the Tlingit stood as our fiercest opponents. They were strong, proud, and skilled in both warfare and trade. When we moved into their lands to establish a foothold, they saw us not as partners but as invaders. Their determination to defend their homeland was unshakable, and conflict between us was inevitable.

The Destruction of Our First Settlement

In 1799, I established a small settlement near Sitka to secure the rich hunting grounds of the region. For a time, it seemed our presence would hold, but in 1802 the Tlingit struck with great force. They attacked our fort, killed many of our people, and drove the survivors into the sea. It was one of the greatest blows Russian America had ever suffered, and it left our power in the region broken.

Preparing for Revenge

I could not allow such a defeat to stand. In 1804, I returned to Sitka with reinforcements, including ships armed with cannon. Our goal was not just to rebuild but to crush Tlingit resistance once and for all. The Tlingit, however, were well-prepared. They built a strong fort of logs and earth, armed with muskets and cannons they had obtained through trade. The battle that followed would test both sides to their limits.

The Battle of Sitka

For days, our ships bombarded the Tlingit fort while my men pressed attacks on land. The Tlingit fought fiercely, returning fire and refusing to yield. But the constant cannon fire weakened their defenses, and their supplies began to run low. At last, they chose to retreat into the forests rather than be destroyed within their walls. We claimed victory, but it was a hard and costly one, remembered in blood and smoke.

The Aftermath and New Archangel

After the battle, I ordered the construction of a new fortified settlement at Sitka, which we named New Archangel. It became the capital of Russian America, a stronghold from which we ruled for years to come. Yet even after our victory, the Tlingit never fully surrendered. They continued to resist in smaller ways, reminding us that our power in Alaska was never absolute. The Battle of Sitka secured Russia’s place in the region, but it also showed the enduring strength of those who called the land their own.

The Decline of the Russian Alaska

My Name is Nikolai Rezanov: Diplomat of the Russian Empire

I was born in 1764 in Saint Petersburg, a child of privilege with access to the courts of the Russian Empire. My education was broad, and I soon entered government service. I gained the favor of powerful men, including Grigory Shelikhov, whose daughter I later married. Through this marriage, I inherited ties to the Russian-American Company, a position that would shape the course of my destiny.

Champion of Russian America

I believed that Russia’s colonies in Alaska needed more than fur traders and hunters—they required imperial protection and a stronger connection to the homeland. As a chamberlain to Emperor Paul I, I secured a charter for the Russian-American Company in 1799, making it an official monopoly. With this, Russia’s presence in Alaska became not just a merchant’s venture but a true extension of the empire.

Voyages to Distant Lands

In 1803, I set sail on the first Russian circumnavigation of the globe with Captain Krusenstern. My mission was diplomacy, to open trade with Japan and expand Russia’s influence across the Pacific. In Nagasaki, however, the Japanese rebuffed my efforts, leaving me frustrated but determined to find another path for Russia’s future.

California and a Love Story

In 1806, I sailed to Spanish California, where our colonies desperately needed food and supplies. There, I met Concepción Argüello, the daughter of a Spanish governor. We fell deeply in love, and I sought to marry her, believing our union could bind Russia and Spain together across the Pacific. But politics and duty delayed our plans, and I left her with promises of return.

Final Journey and Legacy

I never saw her again. On my return north, I grew weak with illness. In 1807, I died in Krasnoyarsk, far from California and the sea. My dreams of uniting empires through trade and marriage ended with me, but my efforts left a mark. The Russian-American Company remained strong for decades, and my love story with Concepción became legend. My name is remembered as a man of vision who sought to secure Russia’s future in America, though fate denied me the chance to see it fulfilled.

Official Chartering of the Russian-American Company (1799) – Told by Rezanov

By the late 1790s, Russia’s colonies in Alaska had grown but were still fragile. Merchants competed with one another, settlements struggled to survive, and the empire’s claims in America were threatened by Britain and Spain. I saw that without imperial support, the colonies would collapse. What we needed was not scattered ventures but a single company, backed by the crown, to manage trade, defend our territory, and govern the settlements in the name of Russia.

My Role in Securing the Charter

As a court official and son-in-law of Grigory Shelikhov, I carried both influence and duty. I used my position to press Emperor Paul I for recognition of Alaska’s importance. I argued that the fur trade brought great wealth, but without order it could be lost to rivals. My petitions were heard, and after much effort, the crown agreed to grant a charter to create a monopoly that would unite the scattered traders into one powerful force.

The Birth of the Russian-American Company

In 1799, the charter was issued, giving life to the Russian-American Company. It was granted the exclusive right to trade, explore, and govern in Alaska and the Aleutian Islands. With this, our colonies were no longer just merchant outposts but official arms of the empire. The company could raise forts, regulate labor, and command ships under imperial protection. It became the backbone of Russian America, and its managers held the power of governors.

Impact on the Colonies

With the charter, our settlements gained new stability. Supplies were more organized, missions were sent to spread the Orthodox faith, and trade routes stretched across the Pacific. Hunters and traders were now tied to a single authority, and expansion into new territories became more deliberate. The company gave Russia the strength to resist foreign encroachment and to dream of holding its place in America for generations.

My Pride and My Vision

Though I would not live long enough to guide the company fully, I took pride in securing its creation. The Russian-American Company was the realization of what Shelikhov and I had worked toward—a formal, lasting empire across the sea. For me, the charter of 1799 was not just a decree of the crown but the moment Russian America was truly born.

Expansion of Settlements & Introduction of Missionaries – Told by Rezanov

With the Russian-American Company formally chartered, one of our first tasks was to strengthen the scattered settlements that had begun under Shelikhov and Baranov. Kodiak remained the heart of our operations, but new posts were established along the Aleutian chain and into southeast Alaska. Each post extended Russia’s reach, securing hunting grounds and defending against rivals. These outposts were more than trading stations—they became the framework of Russian America.

The Role of Sitka

After the conflict with the Tlingit and the founding of New Archangel, Sitka became the capital of Russian America. From there, administration, trade, and defense were coordinated. I envisioned Sitka not just as a military stronghold but as a true colonial center, where families could live, schools could be built, and Russia’s presence would take root for generations. Expansion was not only about fur but about creating a society tied to the empire.

Bringing Faith to the Frontier

Alongside trade and settlement, I believed it was vital to bring the Orthodox faith to Alaska. Missionaries were sent to Kodiak and other posts, tasked with baptizing the native peoples and teaching them the prayers and traditions of the Church. For the empire, this was a way of binding the colonies more closely to Russia, giving them spiritual as well as political unity.

The Work of the Missionaries

The missionaries faced harsh conditions, long journeys, and resistance from those who clung to their traditions. Yet they persevered, learning native languages, translating scriptures, and establishing schools. Through them, many Aleut and Alutiiq were baptized, and the Orthodox cross became a lasting symbol in the region. Their efforts softened some of the divisions between settlers and natives, though they could not erase the pain of conquest.

My Vision for Russian America

I saw expansion and faith as inseparable. Settlements would anchor Russia’s power, while the Church would anchor Russia’s soul in the new world. Together, they would ensure that Alaska was not merely a distant outpost but a true part of the empire. Though my life was cut short, I knew that these efforts had set the foundation for Russian America to grow in both strength and spirit.

Diplomatic Missions to Japan and California – Told by Nikolai Rezanov

In 1803, I joined Captain Krusenstern on Russia’s first circumnavigation of the globe. My task was to act as a diplomat, carrying the hopes of the Russian crown to open trade with Japan. Our empire sought silk, porcelain, and other goods that could strengthen both our markets and our colonies in Alaska. When we reached Nagasaki, I presented myself with gifts and letters from the Tsar, expecting goodwill. Yet the Japanese, closed to foreign influence, refused every offer. After long delays and endless barriers, our mission ended in failure. The doors of Japan remained closed to Russia.

A Shift Toward California

Though disappointed in Japan, I did not abandon diplomacy. I knew that our colonies in Alaska could not survive on furs alone. They were hungry, their supplies unreliable, and their future uncertain. My eyes turned southward, toward Spanish California, where fertile lands and mild climates offered what our northern settlements lacked—grain, cattle, and wine. If Japan would not open its ports, perhaps California could become our lifeline.

Arrival in Spanish California

In 1806, I sailed to San Francisco and Monterey, where I was received by Spanish officials. Though we were rivals on paper, in practice they welcomed me, for they too were isolated and needed allies. I negotiated for food and supplies, hoping to build a trade network that would sustain Alaska. In California, I also met Concepción Argüello, the daughter of the Spanish governor. Our meeting became more than diplomacy—it became a story of love.

A Union of Two Worlds

Concepción and I quickly grew close, and I sought her hand in marriage. I believed our union could serve not only our hearts but also our nations, binding Spain and Russia together across the Pacific. I promised her I would return after securing the Emperor’s permission. To me, she symbolized both hope for my colonies and hope for my own happiness.

The Legacy of My Missions

Though fate did not allow me to return to her, and my journey ended in death before I could fulfill my promise, my missions to Japan and California reflected the same vision. I sought to strengthen Russian America not only through conquest or trade but through diplomacy and alliance. Japan closed its gates to me, but in California, I found both friendship and love. My life as a diplomat was brief, yet it showed how much the future of Russian America depended not only on arms and furs but on the ties we could weave across the seas.

Role of Russian Alaska in Global Rivalries (Spain, Britain, U.S.) – Told by Rezanov

Though far from Europe’s great capitals, Russian Alaska became a stage where empires tested their strength. What began as a handful of trading posts grew into a colony that others could not ignore. Its furs, fisheries, and strategic position made it a prize, and every rival knew that control of the Pacific coast could shape the balance of power in the New World.

Spain’s Northern Frontier

Spain claimed much of the Pacific coast, from Mexico up through California, but its northern frontier was weak. When we settled in Alaska, Spain viewed us with suspicion. Our voyages to California, including my own, brought the two empires face to face. Though Spain welcomed trade to relieve its struggling missions, they feared that Russia’s presence would push southward. Alaska stood as a challenge to their dominion, reminding them that their empire was not unshakable.

Britain’s Expanding Reach

Britain, with its powerful navy and growing presence in the Pacific, was another rival. Their traders came by sea from Canada and beyond, eager for the same sea otter pelts that sustained us. The Hudson’s Bay Company and other British ventures threatened to undercut our trade, and their warships carried a strength we could not match. For us, defending Alaska was as much about resisting British expansion as it was about securing furs.

The Rising Power of the United States

In my time, the United States was young but ambitious. Its merchants sailed from Boston to trade along the Pacific coast, often reaching the very waters we called our own. These Americans brought competition in commerce and dreams of expansion that would one day stretch to the Pacific. Though their nation was small compared to the empires of Europe, I sensed that their hunger for land and trade would grow quickly.

Russia’s Place in the Rivalry

Russian Alaska was more than a colony—it was a claim of empire in the Pacific world. We stood at the edge of global rivalries, our posts and forts reminders that Russia, too, could project its power across oceans. Yet we were always vulnerable, our numbers small, our supply lines weak, and our rivals many. Still, for a time, Alaska placed Russia among the powers competing for dominion in the New World, its fur and its coasts making it a prize in the struggle of nations.

Decline of Russian Interests and Eventual Sale of Alaska (1867) – Told by Rezanov

When I worked to strengthen Russian America, I believed it could become a lasting part of the empire. The fur trade was rich, the lands vast, and the Pacific offered new horizons. Yet even in my time, I knew how fragile our position was. The settlements were small, supplies unreliable, and the distance from Russia immense. Our strength in Alaska rested on ambition, not on firm foundations.

The Waning of the Fur Trade

The sea otter, whose pelts had once built fortunes, became scarce by the mid-1800s. Overhunting devastated their numbers, and with them, the wealth that sustained our colonies. Without this trade, Alaska’s value to the empire began to fade. What remained were scattered posts, costly to maintain, and lands too harsh to support large populations of settlers.

Pressure from Rival Powers

Britain’s growing power in the Pacific, through Canada and its navy, overshadowed our fragile presence. The United States, too, was pressing westward, its ships already trading along the Pacific coast. Russia lacked the strength to defend Alaska if either rival decided to take it by force. The colony, once a symbol of expansion, became a liability in the face of these rising threats.

The Burden of Distance

To govern and supply Alaska demanded enormous effort. Every barrel of flour, every musket, and every tool had to cross Siberia and the stormy Pacific. The empire’s resources were stretched thin, and there were always greater concerns in Europe and Asia. Alaska became an outpost too far, too costly, and too vulnerable to justify holding.

The Sale to the United States

By the 1860s, Russia faced financial strain and the recognition that Alaska could no longer serve its interests. In 1867, the empire sold the territory to the United States for $7.2 million. To some, it seemed a betrayal of all we had worked for; to others, it was a wise decision to cut away a burden. For me, though I had long been dead, the sale marked the final chapter of the story I helped to begin.

A Coda to My Vision

I dreamed of a Russian empire stretching across the Pacific, held together by trade, settlement, and diplomacy. Yet history proved otherwise. Alaska slipped from Russia’s grasp, passing into the hands of a young nation that would one day see its true worth. My efforts, and those of Bering, Shelikhov, and Baranov, were not in vain—they showed the reach of Russian ambition. But the decline and sale of Alaska revealed the limits of that vision, a reminder that empires, like men, cannot hold all that they desire.

Comments